Why you’ll make more by focusing on a portfolio’s total return

Australians love their dividends. And what’s not to love? Those semi-annual dividend deposits are one of the great benefits of investing in a capitalist society.

John D. Rockefeller famously said, “Do you know the only thing that gives me pleasure? It’s to see my dividends coming in”.

One of the most popular strategies for investors, especially retirees, is to buy high dividend paying shares with the aim of generating sufficient income to live on while hopefully leaving the portfolio principal intact.

While this holds obvious appeal, particularly for investors who are anxious about outliving their money, and benefits from dividends typically being far more predictable than earnings, it is a very constricting approach and carries some risks.

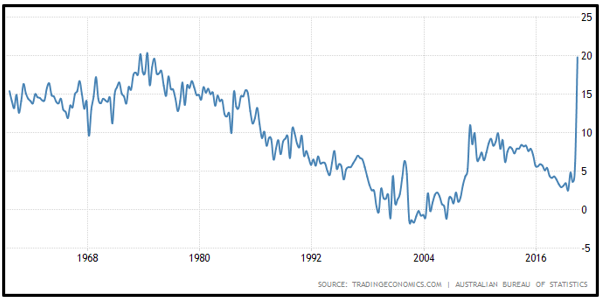

High dividend paying companies tend to offer lower growth. Clearly, if a company is paying generous dividends, it leaves less income to reinvest into the company’s operations. While it’s by no means a universal rule, if a company is able to generate a high return on the equity invested into the business it makes more sense for management to do that rather than pay it out as dividends.

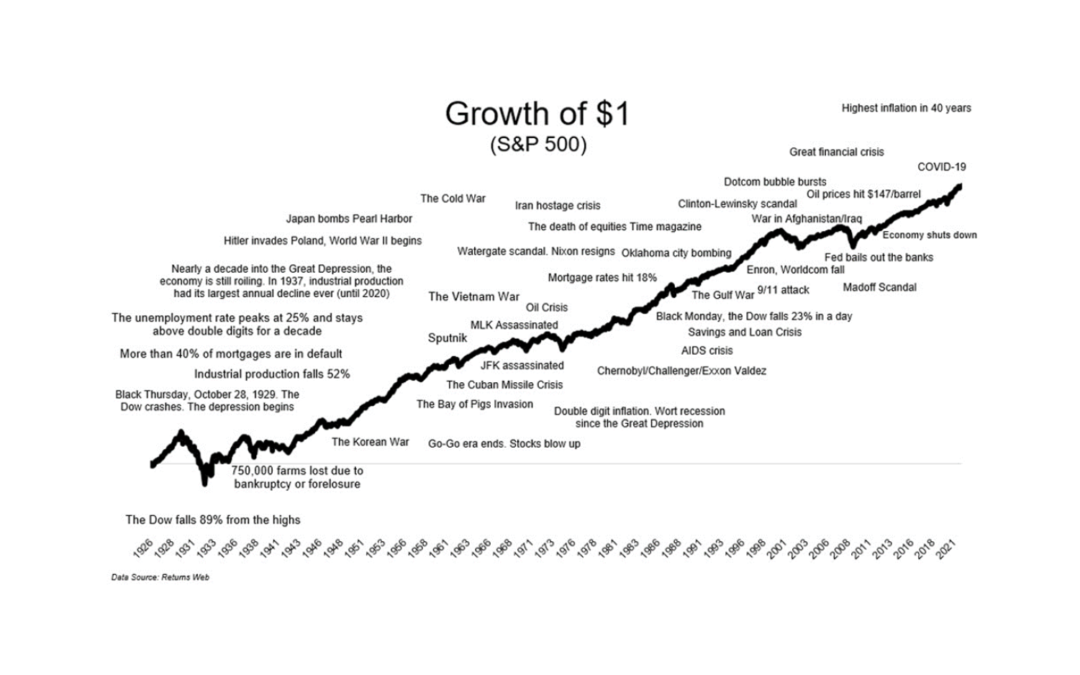

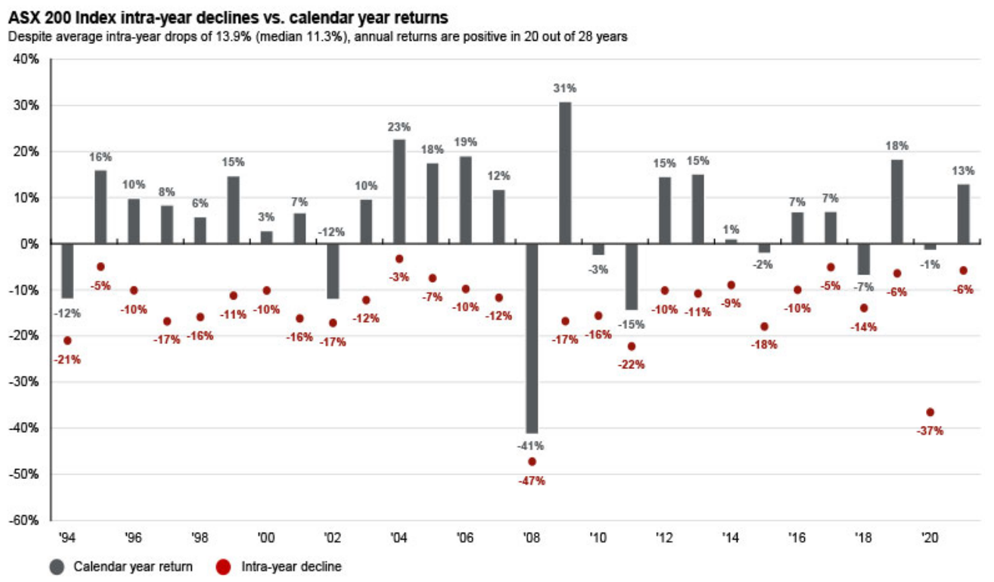

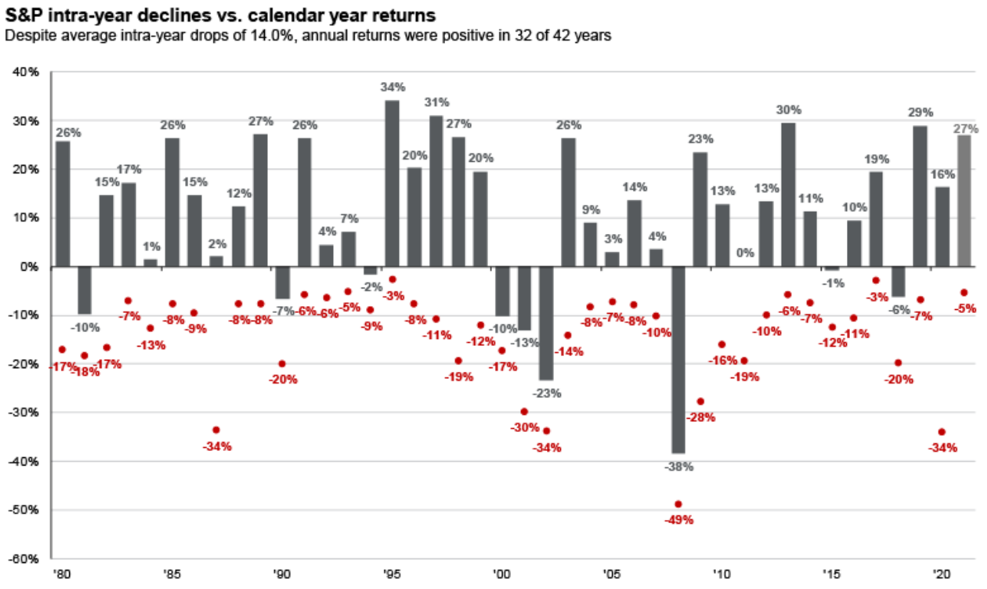

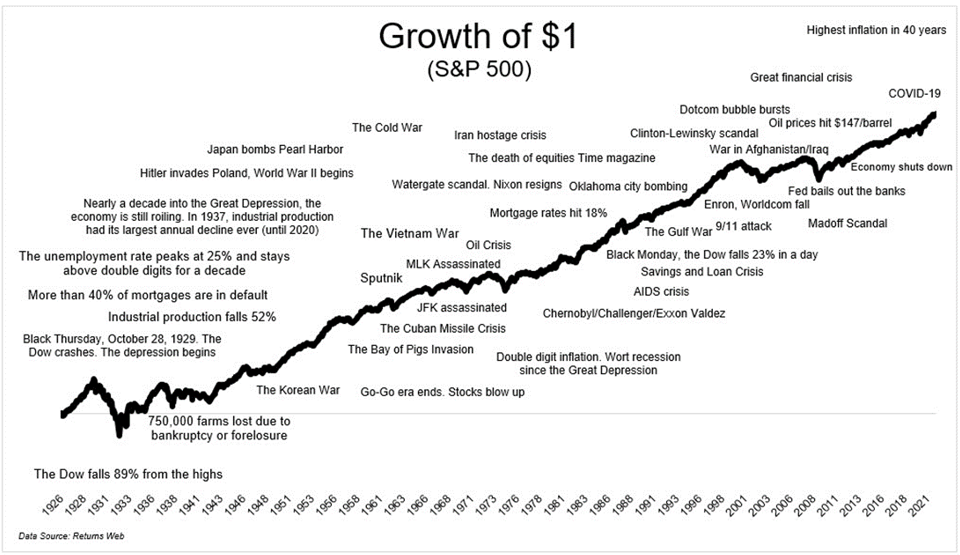

That means a portfolio full of high dividend paying companies is less likely to provide as much capital growth as a more diversified portfolio. If the strategy is to maintain the portfolio’s capital value, then that may not be reason to lose sleep, but over time, it does mean the portfolio won’t benefit as much as it may from the share market’s long history of growth. This is especially true during a period like we saw between 2009-2021 where growth-oriented companies outperformed strongly.

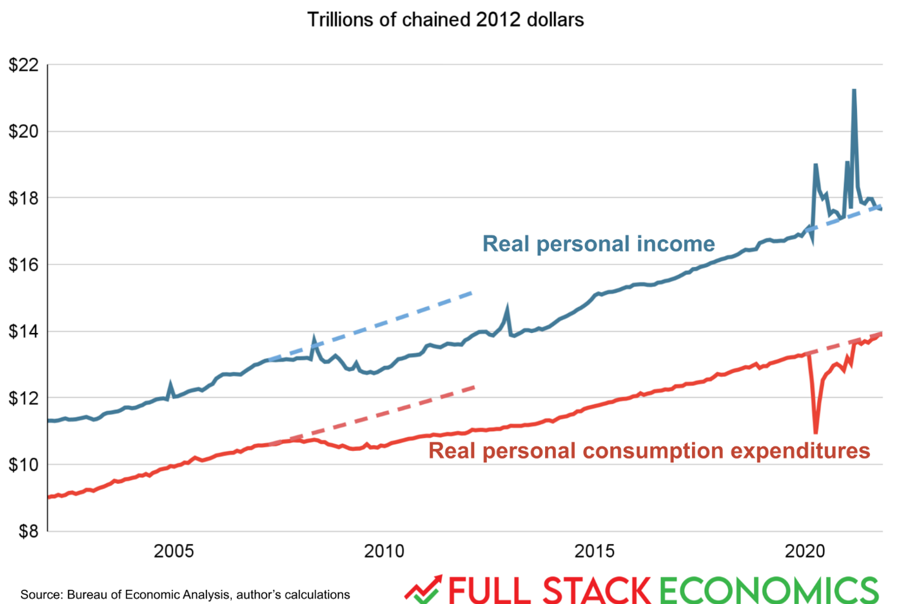

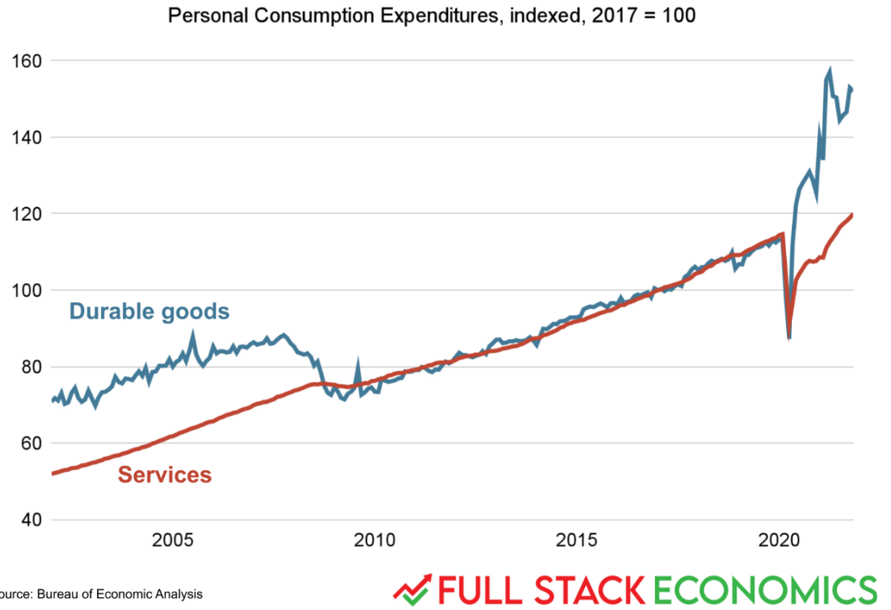

An alternative strategy for investing a portfolio can be to take what’s referred to as a ‘total return approach’, which takes account of both income as well as capital growth. The key to this strategy is to feel comfortable meeting target income requirements by paying a ‘dividend’ from the portfolio by harvesting some of the long-term capital gains.

In other words, imagine an investor with a $1 million investment portfolio who needs $60,000 per year to cover living expenses. If the portfolio generates income of $40,000, they would make up the balance by selling $20,000 worth of investments each year.

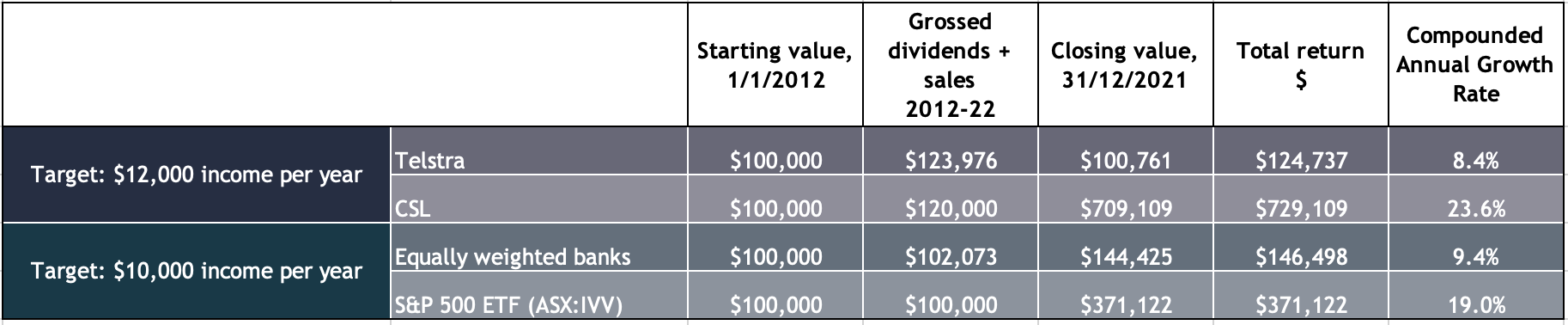

To illustrate the benefits of a total return approach, let’s presume it’s the start of 2012 and two investors each have $100,000 to invest as part of a larger overall portfolio. The first buys $100,000 worth of Telstra shares, which were trading on a prospective dividend yield of an amazing 12 per cent, including franking benefits.

The second buys $100,000 worth of CSL shares, which were trading on a prospective yield of a modest 2.6 per cent. However, they decide to sell as many shares as required at the end of each year to bring the total ‘income’ to $12,000 (to match the Telstra yield).

How did the two strategies stack up over 10 years to the very end of 2021? The Telstra shares will have delivered a total of $103,721 of income, but for the last four years the investor was forced to sell a total of $20,255 worth of shares to maintain the $12,000 targeted income. The closing value of the holding was $100,761, so the total return was $124,737 (i.e. net of the initial investment of $100,000) for a compounded annual return of a still respectable 8.4 per cent.

For our other investor, despite having to sell a total of $70,179 worth of CSL shares over the 10 years in order to meet the $12,000 per year income requirement, the closing value of $709,109 plus that $120,000 of ‘income’ delivered a total return of $729,109, or a compounded annual return of 23.6%.

Clearly you could hardly choose a more favourable pair of stocks to illustrate the point, but if the first investor had split the $100,000 equally between the big four banks for a target annual income of $10,000, after 10 years the total return would have been $146,498 or 9.4 per cent per year.

The same investment into the iShares S&P 500 ETF (IVV) and again selling shares to fund the required ‘income’, would have delivered a total return of $371,122, or a 19 per cent annual return.

Source: MarketIndex.com, Steward Wealth

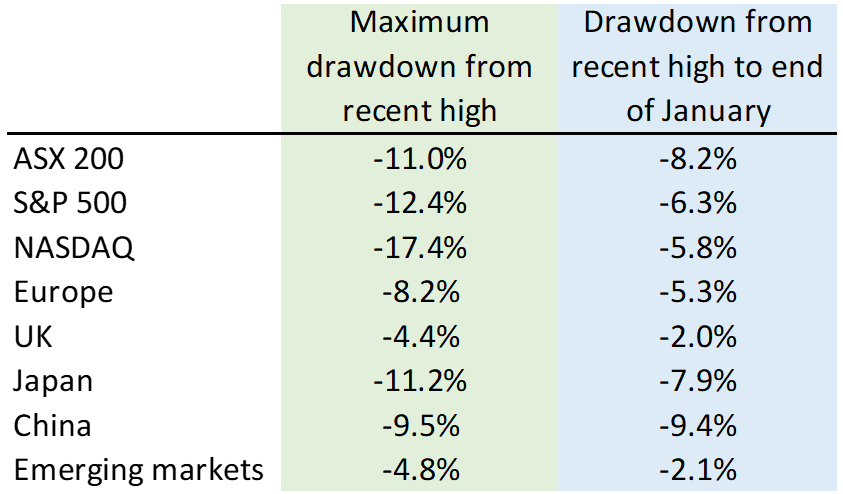

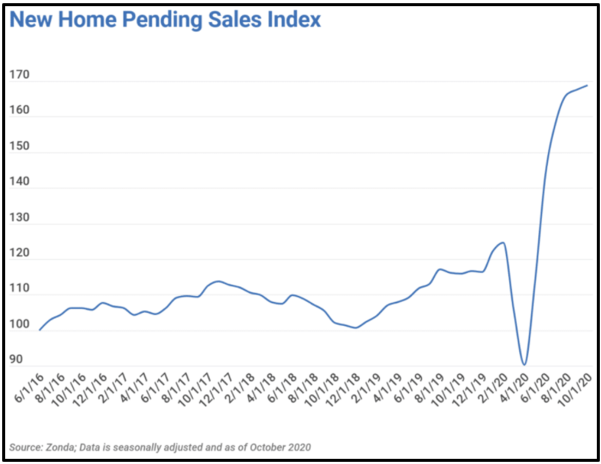

With shares now on sale, smart investors should be mindful of constructing a diversified portfolio that benefits not only from those welcome dividend deposits, but from the inexorable long-term growth that share markets have to offer.