What’s this $3m tax on super? Explaining Division 296 tax

Clients are beginning to hear about a proposed new tax on a portion of their earnings as we approach its likely implementation date. This tax, known as Division 296, is essentially a tax on earnings for those with superannuation balances greater than $3 million. The proposed law is expected to take effect from the 2025-2026 financial year and will impact those whose Total Super Balance (TSB) exceeds $3 million at the end of the relevant financial year.

Although the law is not yet in place, it is likely to be enacted. Some details are still being reviewed as industry bodies provide submissions on the fairness and workability of the new tax.

Key features

- First determination: Sometime after 1 July 2026.

- Personal tax liability: This tax is a personal tax liability, not a fund tax liability.

- $3 million threshold: Applies per individual as of the end of the financial year.

- Earnings threshold: The tax applies to the proportion of your earnings above $3 million and does not differentiate between realised and unrealised gains.

Rate of tax

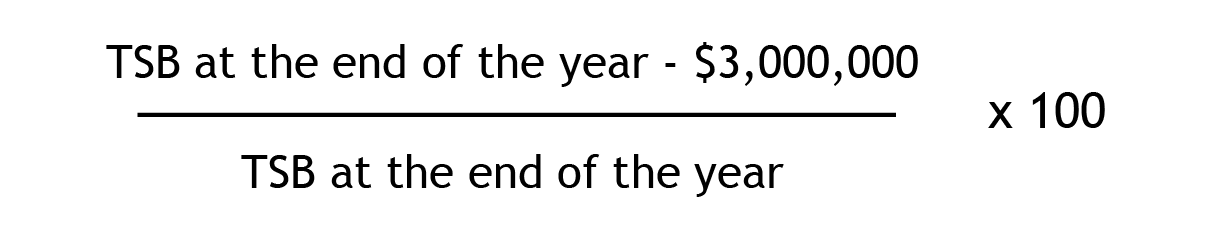

The tax rate is 15%, applied only to the earnings corresponding to the percentage of your TSB that exceeds $3 million.

The formula used is:

Superannuation earnings

The next step in determining the amount of Division 296 tax that you may be liable for is to determine the amount of superannuation earnings for the relevant year.

Basically, you look at the difference between the balance at the start of the financial year (remember this will commence 1 July 2025) and the end of the financial year (30 June 2026).

You then need to make adjustments for contributions and withdrawals made during that year to come up with the adjusted Total Super Balance)

TSB at end of the relevant year + withdrawal total – contributions total.

So, the adjusted amounts will then be as follows:

Current year adjusted TSB – previous year TSB.

Worked example

On 30 June 2026, Cartia has a TSB of $4 million. During 2025/2026, she made a lump sum withdrawal of $100,000 and received concessional contributions of $27,500. Her TSB on 30 June 2025 was $3.2 million.

While Cartia’s superannuation earnings for Division 296 purposes are estimated to be $876,625, only $219,156.25 is subject to the tax. These earnings are attributable to the portion of her superannuation exceeding $3m.

After applying the 15% Division 296 tax rate, her personal liability will be $32,873.44.

While this is a personal tax liability, Cartia may request her superfund pay the tax from her member balance.

Summary and what’s next?

Division 296 is a new 15% tax on earnings (both realised and unrealised) on member super balances over $3m. However, while we expect it to be legislated, it isn’t law as yet as industry groups put forward submissions for certain tax aspects to be reviewed. The areas of contention include:

- Unrealised gains should not form part of the taxable super earnings.

- If unrealised gains are taxed, there should be a rebate if those assets are realised at a lower value in the future.

- The $3m threshold should be indexed

Assuming it is passed to commence in the 2025/2026 financial year as we expect, there is no need to do anything until 2026.

If you would like to discuss your situation, please get in touch.

While there are strategies that you may consider to minimise this tax, the appropriateness depends on your specific situation. Please feel free to contact us and we can talk you through it and help put a strategy in place in due course.