A tax effective alternative to superannuation

One of the reasons superannuation is so popular is the associated tax benefits, but last year the government imposed new limits how much money you can get in to super.

Investment bonds are another tax effective investment strategy that’s been around for years and is becoming popular again as an investment vehicle for tax payers on the highest marginal rate, or indeed anyone paying more than 30% tax. Investment bonds are flexible and easy to establish and manage, but you do need to be aware of a couple of ‘quirks’.

For a start, the opening amount you put into the bond can be whatever you like; unlike superannuation where you are limited in how much you can put in. What you actually invest in will be determined by the provider of the bond, but the range is pretty broad and includes things like managed funds, fixed income, property and cash.

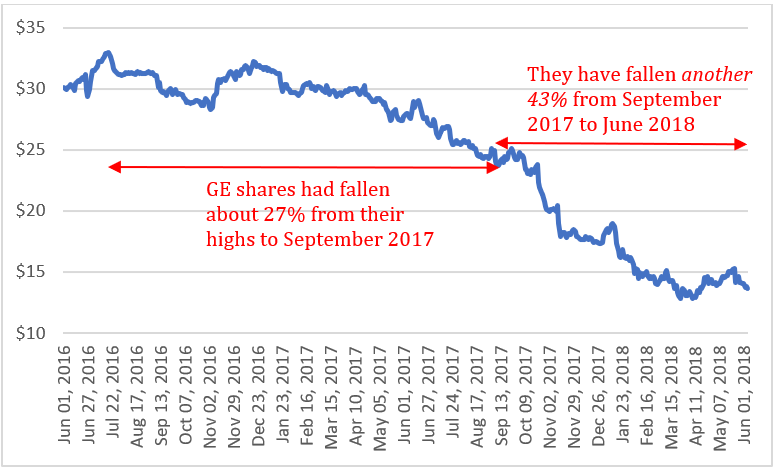

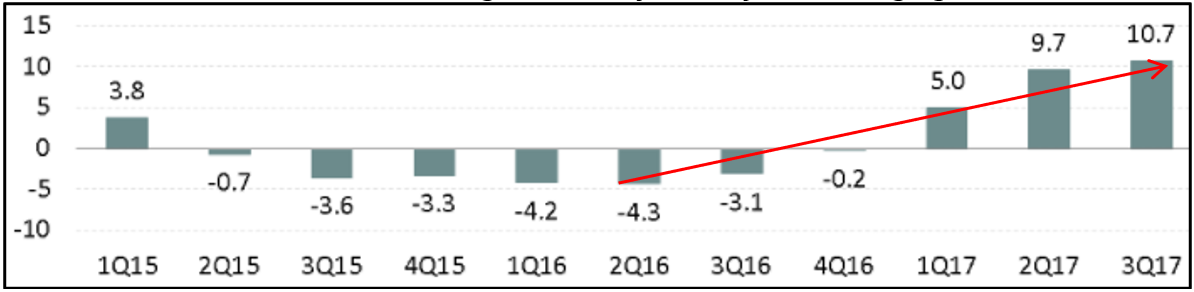

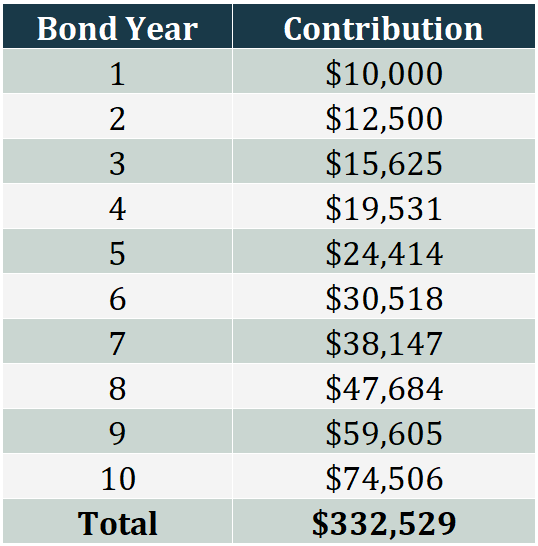

After your initial contribution you don’t have to put any more into the bond if you don’t want to, but you can choose to increase your investment by a maximum of 125% of whatever you put in the year before. So each year the amount invested can grow. Chart 1 shows how much you could invest if you start off with $10,000.

Chart 1: you can start an investment bond with as much or little as you like and and add 125% of your previous year’s contribution every year

Over the life of the bond all the earnings are reinvested, again, much like your super fund. That way you get to benefit from the magic of compounding.

For the life of the bond, which is a maximum of 10 years, the earnings from the investments are taxed inside the bond at 30%, though that rate can be reduced by franking credits. In other words, you don’t have to pay anything out of your pocket while the bond is going, provided (and here’s one of the tricky bits), you let the bond run its full term.

If you do let it go the full 10 years, at the end, you receive all the earnings from the bond and won’t have to pay any further tax on them, plus of course you get back what you invested. That means you’ll have paid 30% tax on the earnings instead of 45%. Importantly, the 10 years starts from the time you make the initial investment, not any subsequent investments. So if you follow the schedule in the table above, the $74,506 invested in year 10 is only tied up for 12 months.

If, for some reason, you have no choice but to break the bond inside the 10 years, you’re allowed to do so, but you’ll have to pay some tax; the amount depends on when you break it.

If you stop within the first eight years, you receive all the earnings but you’ll have to pay the difference between the 30% tax that’s been paid inside the bond while it was in force and your marginal tax rate. In other words, there’s no real tax benefit.

If you stop during year nine, one-third of the earnings are tax-free but you’ll pay your marginal rate on the rest. If you stop during year 10, two-thirds are tax-free.

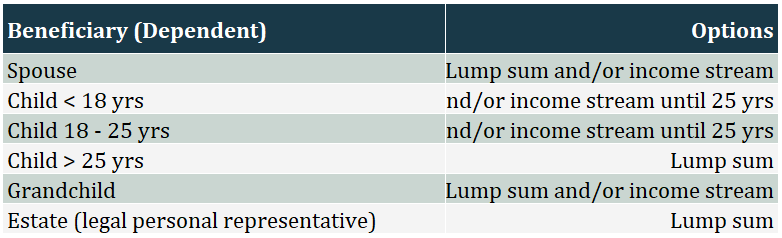

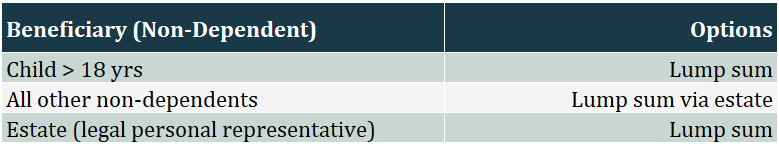

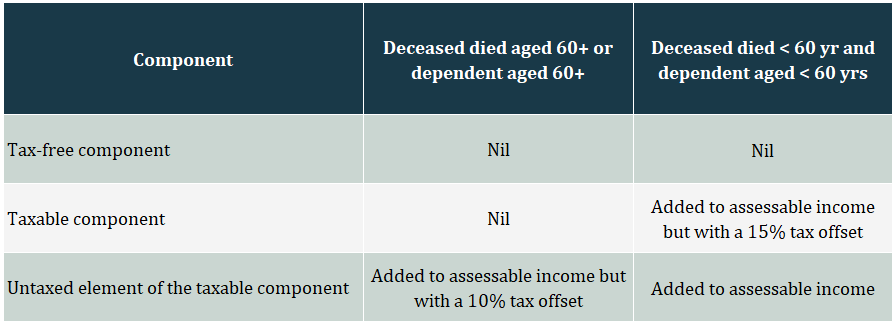

There are other attractive aspects to investment bonds, like you can nominate beneficiaries of the bond without having to make it part of your will. Also, every investment bond has a built in life insurance policy, and the death benefits can go to any nominee tax-free – regardless of how long the bond’s been going for. Finally, unlike superannuation, the rules around investment bonds have been stable since 1995.

There is one downside to bear in mind: because investment bonds are effectively taxed like a company CGT is paid in full when the bond is redeemed, regardless of how long it’s been held. That compares to the 50% CGT discount when you hold an asset in your own name and sell it after 12 months, or in super, where you pay 10% CGT after 12 months.

Investment bonds are making a comeback as a useful tax planning tool for high income earners and can be a great way to save for a specific objective, like a house deposit, education costs or a boost for grandkids.