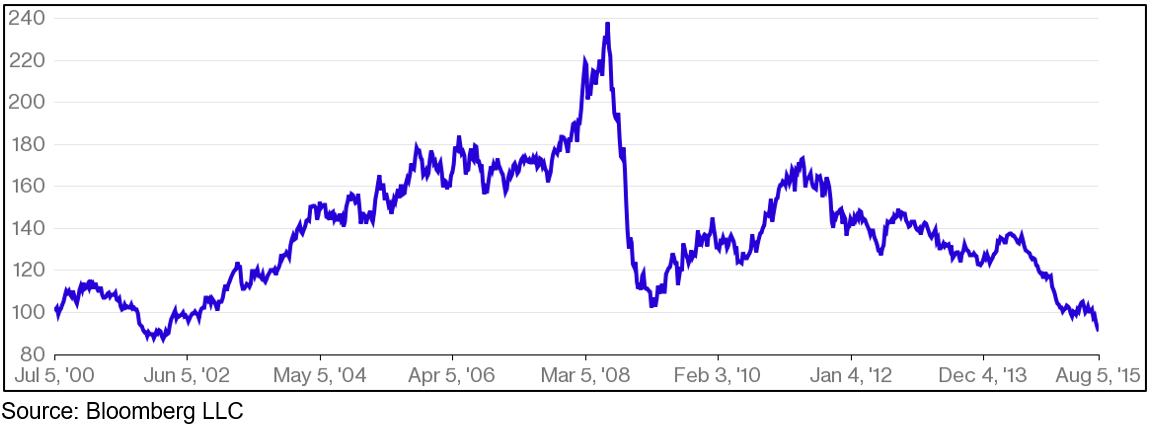

Source: Bloomberg: Asjylyn Loder Jan 9, 2014 “link to full article” When drilling for oil and gas in US shale first emerged a few years ago it was projected to be a game changer for US energy costs and consequently for global oil and gas markets. This article from Bloomberg confirms the impact it has had, with US oil production rising by a record 39% in the last three years and refined oil exports hitting a record in December. Indeed, the US is on pace to become the world’s largest oil producer by 2015! The impact has been far reaching: obviously US industry is benefiting from cheaper energy prices, but 15 European refineries have been closed in the past five years and talk of exporting gas to Asia could put Australia’s lucrative LNG exports at risk. On the flip side, more and more countries from China to the UK are exploring the possibilities of their own shale production. There could even be political ramifications from the reduced reliance on Middle Eastern production.

Unforeseen U.S. Oil Boom Upends Markets as Drilling Spreads

The U.S. oil boom has put European refineries out of business and undercut West African crude suppliers. Now domestic drillers threaten to roil Asian markets and challenge producers in the Middle East and South America. Fifteen European refineries have closed in the past five years, with a 16th due to shut this year, the International Energy Agency said, as the U.S. went from depending on fuel from Europe to being a major exporter to the region. Nigeria, which used to send the equivalent of a dozen supertankers of crude a month to the U.S., now ships fewer than three, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. And cheap oil from the Rocky Mountains, where output has grown 31 percent since 2011, will soon allow West Coast companies to cut back on imports of pricier grades from Saudi Arabia and Venezuela that they process for customers in Asia, the world’s fastest-growing market. “I don’t really think anyone saw this coming,” said Steve Sawyer, an analyst with FACTS Global Energy in London. “The U.S. shale boom happened much faster than people thought. We’re in the middle of a new game. There’s nothing in the past that predicts what the future will be.” Advances in extracting oil from shale rock drove a 39 percent jump in U.S. production since 2011, the steepest rise in history, and will boost output to a 28-year high this year, according to the EIA. While drilling in shale is more expensive than other methods and poses environmental challenges, the prospect of a growing supply is encouraging analysts to predict a more energy-independent nation.

Crude Exports

With U.S. exports of gasoline and other refined products hitting a record last month and the country on pace to become the world’s largest oil producer by 2015, five years faster than the IEA’s earlier predictions, industry advocates such as Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska are calling for an end to 39-year-old restrictions on U.S. crude exports. In a measure of just how quickly the oil market has changed, President Barack Obama unveiled in March 2011 a goal considered so outrageous that correspondent Christopher Mims wrote on the environmental news website Grist that it could be accomplished only by “an economic crash bigger than any ever seen in U.S. history, or perhaps an alien race forcing all of us to take to our bicycles.” Obama said that by 2025 the U.S. would cut crude imports by one-third. It didn’t take 14 years. It took less than three.

End Restrictions

The country is so flush with crude that imports are plunging and drillers are challenging export limits imposed after the 1973 Arab oil embargo. Murkowski, the top Republican on the Senate Energy Committee, called on Obama yesterday to end restrictions and vowed to introduce legislation if he doesn’t. Easing controls would have been unthinkable just three years ago, when uprisings in Arab countries such as Libya pushed crude prices over $100, said Philip Verleger, a former director of the office of energy policy at the Treasury Department and founder of the Aspen, Colorado-based consultant PKVerleger LLC. The boom has been led by drilling in the Permian Basin in West Texas and the oil-rich Bakken shale, which stretches from North Dakota into Montana and Canada. North Dakota and Texas have more than doubled crude output since Obama’s 2011 speech, with Texas pumping more than Iran, according to the EIA, the statistical arm of the U.S. Energy Department, and a Bloomberg survey of producers, oil companies and analysts.

Bone Springs

Drilling is spreading in emerging oil fields in the Rocky Mountain region such as the Niobrara in Colorado and the Bone Springs in New Mexico and spurring a revival of crude extraction around Wyoming’s Teapot Dome formation, home of the first U.S. reserves and the namesake of a 20th century political scandal. Colorado’s production jumped 17 percent in the first 10 months of 2013, Wyoming rose 16 percent and New Mexico added 10 percent, according to the EIA. A record amount of crude is already riding the rails from oil fields in North Dakota, Colorado and New Mexico to California’s fuel makers, according to the California Energy Commission. Companies looking to ship even more include Tesoro Corp., Valero Energy Corp. (VLO) and Plains All American Pipeline LP (PAA), which are planning to build train terminals in California and Washington state, according to company statements and regulatory filings. Plans are awaiting permits or in the planning stages to handle capacity roughly equal to the amount of crude sent to the region by Saudi Arabia.

Asia Demand

If the railway networks on the U.S. West Coast are completed, the region’s refiners will be able to use domestic crude supplies to boost exports to meet rising needs in Asia, where demand for new cars, electricity and air conditioning is boosting energy consumption. China, already the world’s largest importer, will rely increasingly on crude from the Middle East and refined fuels from the U.S. to meet its consumers’ growing demand. An increase in the number of U.S. cargoes to Asia might force Saudi Arabia to cut its output to head off a worldwide glut, Verleger said. As the de facto leader of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the kingdom is monitoring signs of potential oversupply as Iraq and Libya try to boost output and Iran increases exports as international sanctions are loosened, he said. “It’s another outlet for North American oil products and means more supply for the rest of the world,” said Andy Lipow, president of Lipow Oil Associates LLC, an energy consultant in Houston. “The West Coast is behind the rest of America as far as getting crude by rail. It will increase supply and help the consumer.”

Hydraulic Fracturing

The U.S. gains were made possible by innovations in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, that have unlocked fuel trapped in underground rock. The technology allows producers to bore horizontally, then use explosives and a high-pressure stream of water, sand and chemicals to blast open fractures that free the oil. The process comes with environmental risks. A 2011 U.S. government report found fracking chemicals in groundwater in Pavillion, Wyoming, and in June, 47 people died when an unmanned train carrying Bakken crude derailed and exploded in Lac Megantic, Quebec. Crude from the Bakken may be more flammable and more dangerous to ship than other types of oil, the U.S. Transportation Department said Jan. 2. Fracking is also more expensive than traditional extraction. Drilling a horizontal shale well in the Bakken can cost 10 to 20 times what a vertical well might cost, according to Austin, Texas-based Drillinginfo Inc. Production from shale wells declines by 60 percent to 70 percent in the first year, while output from traditional wells diminishes by as much as 55 percent in two years before flattening out, according to Drillinginfo.

Import Need

One reason the U.S. still depends so much on imports is that demand continues to outstrip domestic supply. Another reason is the quality of crude its refineries can handle. Many of them performed expensive upgrades in the past decade so they could process oil from overseas that was more difficult to turn into transportation fuel. Gasoline users and diplomats benefit from the surge in U.S. production. While the 2011 Libyan uprising had U.S. consumers paying almost $4 a gallon for gasoline, pump prices declined 1.3 percent last year and averaged $3.31 a gallon yesterday, according to AAA, the largest U.S. motoring organization. That was even after sanctions cut off more than 1 million barrels a day of Iranian oil exports. Starved of their primary source of cash, the Islamic republic’s leaders in November reached an agreement to curb its nuclear program. “It took time to realize how significant this transformation was going to be,” said Jason Bordoff, who was an energy adviser to the National Security Council and helped draft Obama’s 2011 speech. “We were able to impose pain on Iran without imposing pain on ourselves.”

Rail Routes

New rail routes and pipelines are carrying increasing supplies of crude from North Dakota, Oklahoma and elsewhere to refiners in New Jersey, Louisiana, Texas and Pennsylvania. They are in turn sending cargoes of diesel to London, Rotterdam and Antwerp, Belgium. U.S. fuel exports to the Netherlands, a major import hub for the region, reached a record in September, according to the EIA. The one-two punch of declining crude imports followed by rising fuel exports hit the refining industry in Europe and the U.K. particularly hard. That’s because refiners outside North America typically buy oil based on the price of Brent crude, a North Sea grade that last year cost an average of almost $11 a barrel more than West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. benchmark. WTI futures on the New York Mercantile Exchange settled at $92.33 a barrel today, $14.82 below the Brent price of $107.15 on ICE Futures Europe in London. It was the widest spread at the close since Dec. 3. The spread widened to a record $27.88 a barrel in October 2011. “When historians write this story 10 or 20 years from now, they are going to look at a very different U.S.,” said Verleger, the former Treasury Department official. “Everything has changed.”