Why have we got such low wages growth?

One of the enduring economic conundrums over the past few years has been declining real wages growth across developed nations, because if wages aren’t growing then it’s a serious headwind for an economy to grow. The strange thing is, it’s difficult to pin down a particular reason for the flat wages, and the ominous thing is, you can make an argument that the combination of technology and globalization will continue to keep the pressure on.

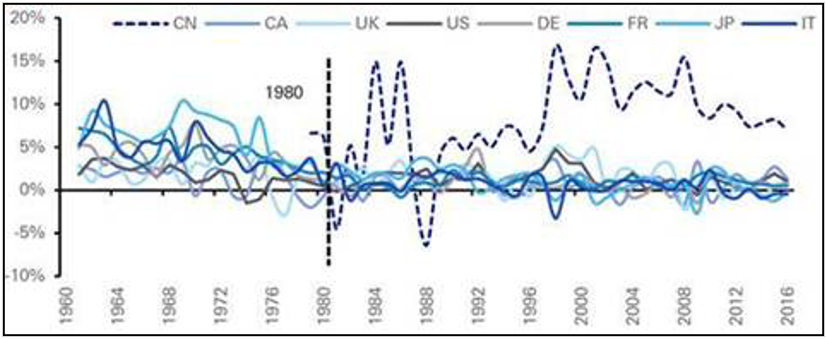

Weak wages growth is endemic across developed nations

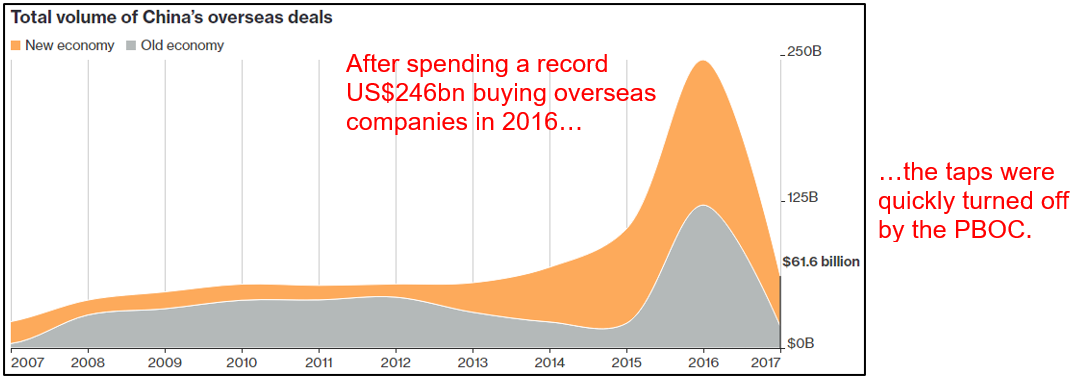

The only country that’s shown strong positive wages growth across the G8 since the start of this century is, surprise! surprise!, China – see chart 1 – but even that has recently been on a downward trend.

Chart 1: Year on year real wages growth across the G8

Source: Deutsche bank

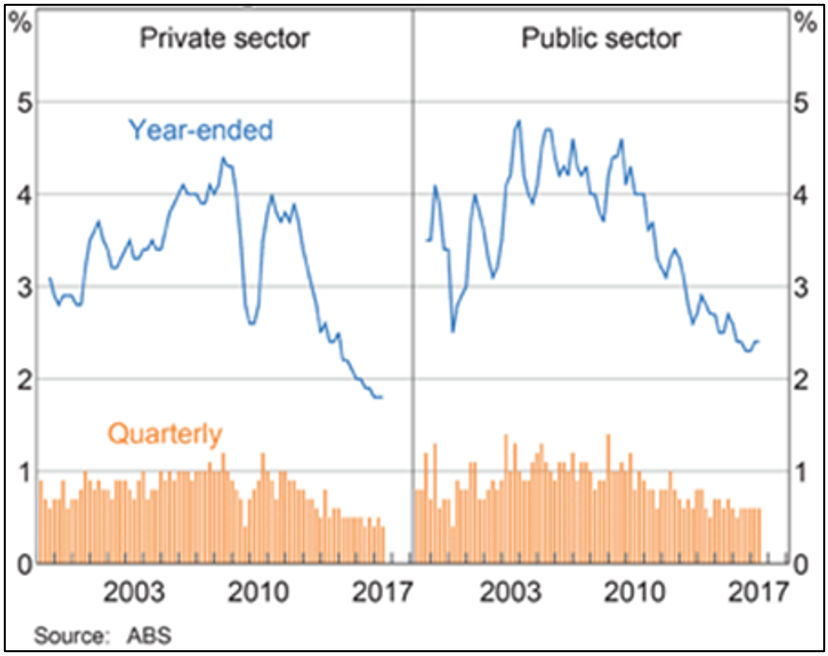

And Australia’s wages growth started to weaken after the GFC – see chart 2.

Chart 2: Australian wage price index growth

But why…

It’s worth remembering from the outset that like all things economic, you can point to many plausible reasons to explain low wages growth; and any one of them, or combination of them, could be right – it could also easily be the subject of a book as opposed to an article.

A couple of the popular ones are:

1. Low productivity growth

This argument is essentially that companies will only pay workers more if they are actually more efficient. So if a mining company increases its profits because the iron ore price has gone up, as opposed to its workers digging more ore out of the ground, then the workers shouldn’t necessarily benefit from that increased profitability.

Chart 3 shows quite a close relationship between Australian wages growth and productivity over the past five years, but very little similarity before that. So it begs the question, why would there suddenly be a close relationship?

Chart 3: Australian unit labour costs growth

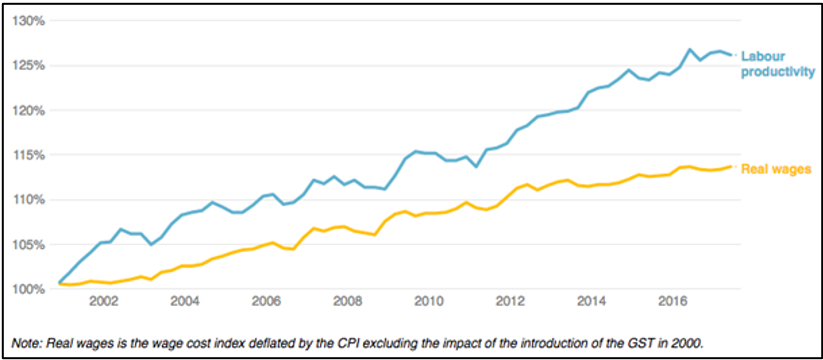

Also, while productivity growth has stagnated since the turn of the century in most developed nations – another of the great economic mysteries of our time – in Australia it’s risen about 25%. But chart 4 shows wages growth has been about half productivity growth over that time.

Chart 4: Australian real wages and productivity growth

2. Poor company profits

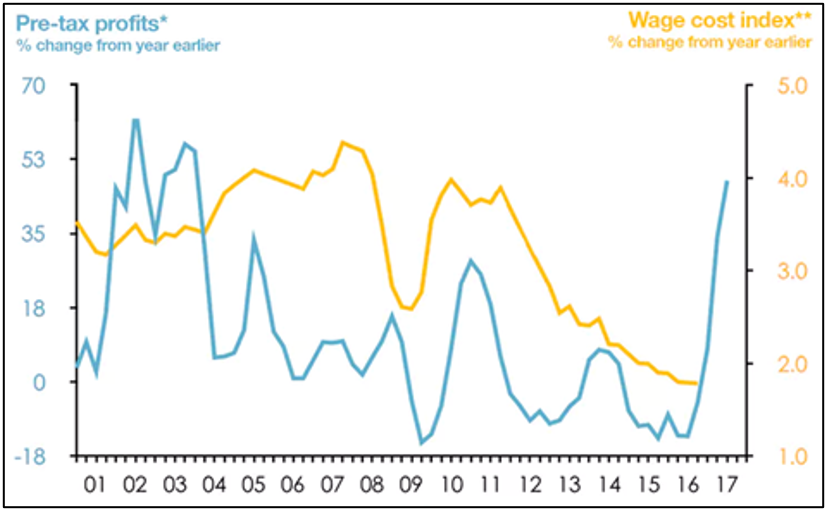

It makes sense that if companies aren’t making good profits they’re not going to pay higher wages. Chart 5 shows there is some relationship between company profits and wages, but it’s not a particularly close one.

Also, the wages growth line in the chart is lagged by nine months, to allow for a rise in profits to feed through to wages, but despite the sharp rise in pre-tax profits starting some 18 months ago, the latest data show Australian wages growth is, as Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe recently noted, “the slowest since at least the mid-1960s”.

Chart 5: Australian pre-tax company profits and wages

Source: ABS, Saul Eslake, The Conversation

Note: pre-tax profits are rolling four quarters and wages are lagged three quarters

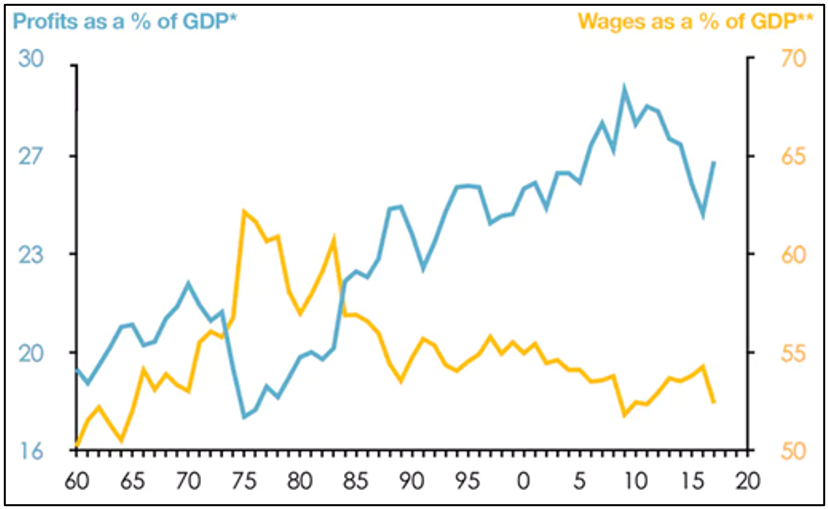

And for a bit of longer-term perspective, chart 6 shows the share of the overall economic pie going to profits continues to trend up toward record levels, while the share going to wages is doing the opposite.

Chart 6: The share of Australian national income going to profits vs. wages

Source: ABS, Saul Eslake, The Conversation

So arguments based on profits doesn’t seem to stand up either.

3. Regulatory changes

Once upon a time Australia, and much of the developed world, operated under ‘wage indexation’, but the inflationary ‘wages spiral’ of the late 1970s put an end to that.

Since the 1980s the combination of reduced union representation and successive governments on both sides of the political fence seeking to link wages growth to productivity has reshaped how wage rates are negotiated.

This actually strikes me as a more persuasive argument for the long-term reduction in labour’s bargaining power.

Technology and globalization

I have a slightly more convoluted theory on why wages growth is weak and it’s to do with the effects of technology and globalization combining to seriously undermine any bargaining leverage wage earners can wield.

About 25 years ago China set out to become the world’s factory, exploiting a vast workforce that was paid a fraction of their western counterparts. From that point the pressure on manufacturing wages grew as companies that compete against manufactured imports have to do the math: at what point does it no longer make sense to produce locally and you either have to send the work offshore or close down?

Currently about half of Australia’s manufactured imports come from low-wage countries, compared with less than 10%, 40 years ago. This is important given that 80% of the value of Australia’s imports comes from manufactured goods.

The only way developed world manufacturers could hope to compete was to increase efficiency, which has translated into replacing as many people with machines as possible and keeping down the wages of those workers that remained. Even today, with the inexorable rise in robotics and AI, the so-called ‘on-shoring’ of manufacturing back to developed countries is because those factories are largely automated and energy and logistics can be sourced cheaply enough to make it worthwhile.

That has seen the gradual elimination of well paid but low skilled manufacturing jobs where unions used to play a role in helping secure wage rises. One upshot of this for Australia has been the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector, with services now representing more than 60% of GDP and 80% of employment.

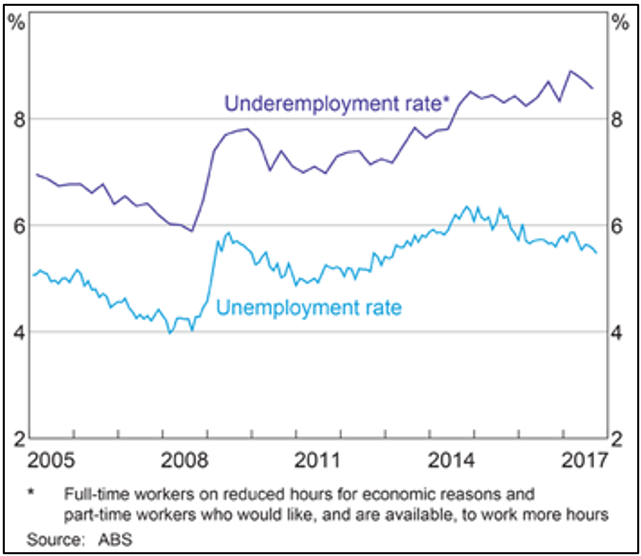

Now the unskilled and displaced are often ending up in the growing low paid services sector, such as aged care services and hospitality, which is reflected in our unemployment data: while headline unemployment over the last three years has declined to 5.5%, the underemployment rate has been trending upwards since the GFC from 6% to now be 8.5% – see chart 7.

Chart 7: Australia’s labour market – underemployment continues to trend upwards

The long reach of globalization is now starting to touch the upper end of the services sector as well, with increasing numbers of accounting firms, engineering, software development, design and what-have-you ‘off-shoring’ work to the likes of Vietnam and India. If Australian accountants and designers want to compete they either have to stay ahead on the quality curve or reduce their costs (wages).

With the rise of AI it’s not just low skilled jobs that are being targeted, rather it’s any industry where wages form a high proportion of costs. For example, in the U.S. there’s a radiology ‘robot’ that is 50% better than its human counterparts at diagnosing particular tumors, and law firms are talking about cutting the human cost of litigation from 70% to 2% by using technology.

It’s reached the point now where if labor demands higher wages for a multitude of jobs they are battling an equation that has offshore workers or robots on the other side of it. Combine that with record levels of household debt, the risk of losing a job means for big chunks of the workforce there’s not much incentive to go in hard on your annual salary review.

The benefits go to capital

The big winner from the suppression of wages is, of course, the owners of the capital, that is, the companies. As we saw above profits are strong and getting stronger.

If that’s the case it makes it all the more critical that companies pay their fair share of tax. If wages are stagnant so too will be income tax revenue yet countries like Australia face a growing welfare and healthcare burden. And yet for now countries across the world are engaged in a race to the bottom for corporate taxes; a beggar thy neighbor strategy that risks impoverishing everybody.

Like I said, there’s a multitude of reasons to account for low wages growth, and just as with most economic arguments there’s almost no way of proving which one is right. Admittedly some of the trends have not existed long enough to make anything other than assertions and it may change on a dime. I’m by no means arguing we should try to fight a rising tide, but there are seriously important issues involved that will shape our economies and societies in the years ahead.