Steward Wealth June 2020 quarterly outlook

Welcome to our Steward Wealth quarterly outlook video, a brief overview of where we see markets now and how we’re positioned.

Welcome to our Steward Wealth quarterly outlook video, a brief overview of where we see markets now and how we’re positioned.

With the inundation of COVID-19 news coverage we’re all having to live through, I thought I’d jot down a few thoughts on a bunch of different topics related to financial markets. Short and sweet(ish).

While every bear market’s different in terms of the cause, depth and duration, this one stands out because it’s a rare occasion where it started in the real economy and transmitted to the financial markets, rather than the other way around. You could argue the 1970’s OPEC-related slump was similar, but even there, the macro picture was very different with high inflation. That makes it harder to get a grasp of how things might play out and how effective the rescue measures from governments and central banks will be.

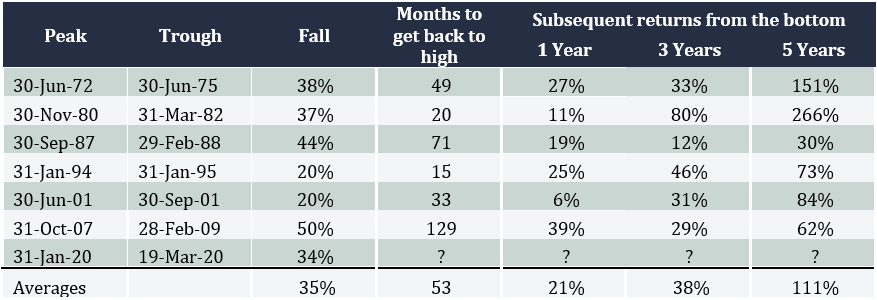

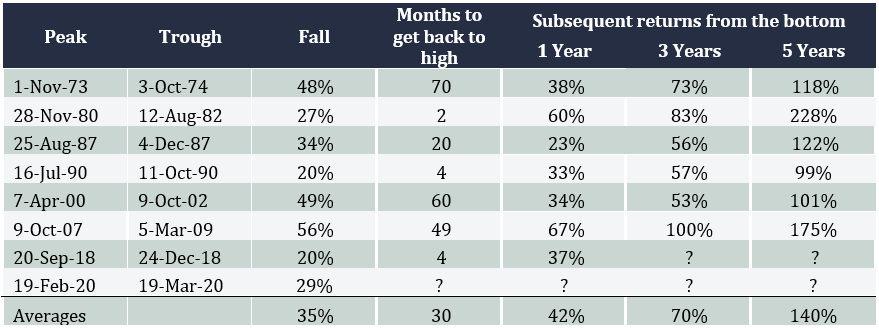

Over the last 50 years we’ve seen seven bear markets in Australia (that is, falls of more than 20%), including the current one, with an average decline of 35%. The US has also seen six with an average fall of 42%. The current ‘virus-crisis’ has seen our market drop 34% to the close on 19 March and 29% for the US.

One of the things that makes this different is because the crunch is coming from both the supply side and the demand side. When China shut down, those companies that rely on Chinese manufactured goods for their own business were struggling to fill the gap. And now that more and more of the world is going into quarantining and isolation, consumers aren’t spending. So the proverbial double-whammy.

What level of economic slowdown is being priced in by share markets right now is tough to say with any accuracy.

Asset allocation consultant, Heuristic Investment Systems, reckons for the US, in an ‘average recession’ where GDP drops by 2%, a bear market tends to see the S&P 500 fall by 25-30%, and in a deeper recession, like the GFC, the average fall is 40-50%. On that basis, the markets are currently pricing in an average recession.

By contrast, the Bloomberg Chief Equity Strategist, Gina Martin Adams, says the S&P 500’s ‘trailing price to earnings (PE) ratio’, which refers to the earnings that were reported by companies over the past year, which at least has some certainty, is now about 15. Compared that to her ‘fair’ multiple, it implies a worse than average recession with earnings declining 22% over the next year.

The tables below show how far Australian and US share markets have fallen during each bear market over the past 50 years, how long they took to get back to where the index started, and then what returns were like 1, 3 and 5 years after.

For Australia, the average three year compounded annual return works out to be more than 11%, and in the US it’s an amazing 19%. Given it appears interest rates are likely to stay very low for a long time, that represents an attractive return, and is one of the arguments in favour of a sharp rebound in shares.

The VIX index in the US measures share market volatility, and the chart below shows it’s hit eye-popping levels in the past couple of weeks, every bit as stomach-churning as the GFC.

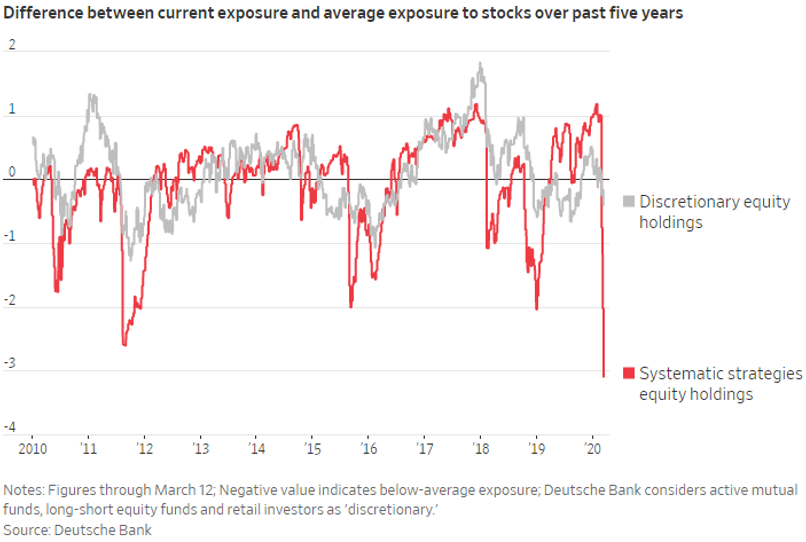

While it’s almost impossible to get definitive numbers, it appears much of the volatility is coming from so-called ‘systematic strategies’, essentially computer-driven funds that trade automatically depending on all kinds of different variables, like momentum or volatility or depending on what’s happening in other markets like bonds or commodities, and then there are the ‘high frequency trading’ funds that aim to jump in ahead of any trades at all. The chart below shows how sharply some funds have dumped their equity positions.

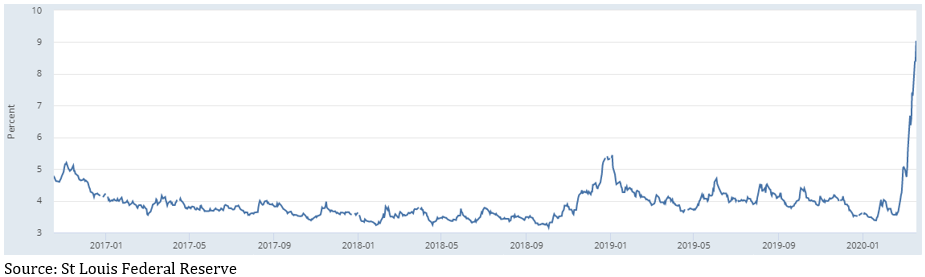

Bond markets have been every bit as crazy as share markets, but in a scarier way. Credit markets facilitate the flow of money around the financial system, with trillions of dollars’ worth of deals being done around the world on a day to day basis. It’s these markets that keep the banking system working properly.

Last week, however, the flow was getting choked off because companies were frantically trying to get their hands on cash. Large companies will typically arrange lines of credit with their banks that they can draw on when needed. If companies think there’s a risk they might need cash urgently, because, for example, their business has all but closed down during a quarantine, they’ll go to their bank and draw all that cash out. But there’s a limit to how much cash banks will have on hand, so when they started getting hit up by their customers, they had to go to the credit markets and try to raise cash by selling bonds. However, when everyone’s trying to raise cash at the same time, a market can quickly run out of buyers, so the risk premium they’re willing to trade at rockets (another way of saying the price they offer to buy at goes down), as shown in the chart below, and that’s how the financial flows were getting choked up.

Fortunately, the central banks were able to ride to the rescue and pump liquidity into the system to calm things down a bit, but we’ve seen similar huge jumps in what’s called ‘credit spreads’ across the whole credit market, right around the world, which is seeing a sharp repricing of corporate bonds.

In current markets, central banks and governments have quite different roles to play.

Central banks are focused on keeping credit markets operating, and between them they’ve promised to inject trillions of dollars to make sure that happens. That was a big part of the package of measures the Reserve Bank announced this week, which included cutting interest rates to 0.25% to reduce the cost of credit and basically saying the rate will stay there for as far as we can see, and it’s making some $90 billion of funding available to banks to lend out for which it will charge them only 0.25%. It also said it’s going to try to make sure the Australian 3 year bond trades at a yield of 0.25% and finally announced it’s going to join the quantitative easing brigade.

The US Fed has also cut rates to basically 0%, so has the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The ECB was already there (in fact their rates are negative) plus it said it will expand its balance sheet by €750 billion and allow qualifying banks to borrow up to €2 trillion at a rate of -0.75% – that’s right, they’ll pay banks to take the money from them!

There will be howls from free marketeers criticising the central banks for supporting asset prices, but that’s an unfair characterisation of what they’re doing, which is more like keeping the financial plumbing open to provide a bridge to governments’ fiscal spending.

And governments have certainly said they’ll spend. After years and years of central banks begging governments to open their wallets, we’ve seen what looks like massive programs being announced: $1.2 trillion in the US, £330 billion in the UK, €1 trillion from European governments to guarantee business loans, and, of course, what appears to be a relatively paltry $17 billion here in Australia. While they sound like huge numbers, rest assured, governments will need to do more if they want to backstop their economies.

This may finally be the time for governments and economists all over the world to wrap their heads around Modern Monetary Theory.

We’ve been fielding lots of inquiries from clients asking when they should buy but unfortunately there’s absolutely nobody on the planet that can give you a good answer to that question. What I think I can say is the market will start to recover once it believes the odds that we’re through the worst of it go to 50.1%, from 49.9%, but exactly how that can be judged I don’t know. It could be a slowdown in the rate of new cases, or even confirmation that current treatments are indeed working, or acceptance that governments will indeed spend enough to backstop economies.

Given the hopeless execution by the Trump administration in the US you’d have to think they have a long way to go, and here in Australia numbers are still doubling every 2-3 days.

One thing’s for certain, share markets are very cheap once again, and the further they go down the higher will be the returns on the other side. If you’re in the lucky position of being able to invest, don’t fall for just buying the most beaten up stocks, who knows, some of them may never recover. Similarly, if you already own shares, you should ask yourself if you’d buy the same ones now. Rather, my suggestion would be to think about the portfolio you wished you’d owned just before things went pear-shaped, and target that.

It’s impossible not to sound cliched, but these are genuinely extraordinary times, especially for Australia. Having endured a summer where it felt like the whole country was on fire, we now have a global pandemic wreaking economic havoc. I wish you all the best and stay safe.

As trustee of a SMSF, you have many obligations to ensure the smooth running of your fund. One such obligation, which is often overlooked, or inadequately prepared, is your fund’s investment strategy.

The Australian Tax Office (ATO) has issued letters to nearly 18,000 SMSF trustees as part of a campaign to ensure trustees are aware of their investment obligations.

The primary concern is ensuring that trustees have considered the diversification and liquidity of their assets when formulating and executing their fund’s investment strategy.

Importantly, it should be noted the ATO is not attempting to regulate and limit the control and freedom SMSF trustees have, but rather ensuring that if trustees wish to invest their assets in a certain way that they must clearly articulate their reasons for doing so.

An investment strategy should be considering the SMSF’s blueprint when dealing with the fund’s assets to ensure the fund’s investment objectives and the members’ goals are met. It provides the parameters to ensure you invest your money in accordance with that strategy. This is where the ATO has a primary function to ensure that trustees act in accordance with these obligations. Strategies can change, and there is no reason why you can’t change the way you invest. However, your investment strategy should be updated to reflect this.

An SMSF investment strategy must take into account the following items:

An important requirement for you as trustee of your SMSF is to have an investment objective and a strategy to achieve that objective in place, before you start to make decisions about how you want to invest your SMSF’s money and change the investment objectives you have set for your SMSF at any time.

It’s not uncommon for SMSFs with lower member balances to find diversification a challenge as there is limited money to invest. Nonetheless, you are still required to demonstrate that you adequately understand and mitigate the associated investment risks.

If you find yourself in this position, it is important your investment strategy reflects these risks.

If you have invested in a large illiquid asset such as real property which may form the majority of your fund, it is timely to ensure your strategy reflects the concentration and liquidity risk associated with this investment.

For example, we met with a trustee who was running an account-based pension within his SMSF. His fund was fully invested in just the one asset being a commercial property. The challenge he faced each year was that the net rental income wasn’t sufficient to cover his minimum pension payments and the costs of running the fund. He relied on making annual contribution to his fund in order meet his pension obligations. This liquidity risk wasn’t adequately reflected in his investment strategy.

Where you have an investment strategy in place that deals with these risks and can provide the necessary evidence to support your investment decisions, no further action is expected.

Where your fund has not complied with its investment strategy requirements under superannuation law, you may be liable to administrative penalties being imposed by the ATO, as Regulator of the SMSF sector.

Your investment strategy does need to be reviewed at least once a year and this will be evidenced by your approved SMSF auditor. It is also important to review your strategy whenever the circumstances of any of your members change or as often as you feel it is necessary. The following practical tips will help you keep on top of your obligations:

If you need assistance with your fund’s investment strategy, please feel free to give us a call to arrange a time to meet so that we can discuss your particular requirements in more detail.

(notes from a conference)

For fear of sounding like a real nerd, anyone even remotely interested in financial markets will appreciate how exciting it is to have an audience with three international central bankers. I got that opportunity, amongst other things, this week at the twentieth anniversary of UBS’s Greater China Conference, held in Shanghai over Monday and Tuesday.

It was my first time in China, and while suggesting Shanghai is representative of China is like saying the same thing about Sydney and Australia, I did come away with a changed impression and understanding of the country; but I’ll come back to that, first the exciting stuff.

Full credit to UBS that they were able to get three rock star central bankers for this presentation: Dr Bill Dudley is the President of the New York Federal Reserve, Dr Raghuram Rajan was the 23rd Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and the former Chief Economist and Director of Research at the IMF, and Dr Min Zhu is a former Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China. One thing to bear in mind, however, while these guys are super smart and extraordinarily well connected, they don’t possess a working crystal ball and what they say is still a (very well informed) best guess.

Their respective views of the ‘new normal’ were extremely close to each other: an ongoing environment of slow growth, low unemployment and low inflation – in other words, no meaningful change from what we’ve experienced over much of the past 10 years. Given the similarity of their outlooks, I can only presume that, for now at least, they don’t see anything on the horizon that’s going to cause things to change much.

To me, the most interesting part of Dr Dudley’s message was his candid acknowledgement that if interest rates are as low as they are now when the next recession hits, there’s obviously not much room to cut them in order to support a recovery. While he acknowledged central banks do have other (read unconventional) tools at their disposal, such as quantitative easing, he argued monetary policy alone will not be sufficient to pull the economy out of recession and reiterated several times they will definitely need fiscal policy, so changes in government spending, to do some, if not a lot, of the heavy lifting.

That is an identical position to most central bankers, including Australia’s Dr Philip Lowe, who have collectively been saying that monetary policy is reaching the limits of what it can do and have been pleading with governments to open their wallets and spend. Dr Rajan also said that while unemployment is very low across the world, job dissatisfaction is relatively high because the quality of a lot of those jobs is poor, and this is something fiscal policy is far better placed to address than monetary policy.

Importantly, and as you’d expect, Dr Dudley also stuck with the Fed’s current script that they are in no hurry at all to raise rates, and will be happy to let inflation in the US run above its 2% target level before they increase from the current 1.75%. That sits well with the market’s current view of where interest rates are headed and is considerably more optimistic than UBS’s US Chief Economist, who spent 14 years at the Fed, and is forecasting three rate cuts this year in response to a weakening economy.

Dr Rajan gave his rundown of what he considers to be the five major influences on economies, none of which will surprise anyone:

Dr Min commented that all technological change is disruptive to the extent that it usually means an existing system is changed in favour of the new, and he pointed to the possibilities that 5G brings with the ‘internet of things’. It took China five years to reach some 3.7 billion 4G devices and it’s targeting all of those to be switched to 5G within 2.5 years, bringing with it the benefits of bigger, faster, fatter pipes of data.

He also believes that ageing demographics and the gradual reduction in the proportion of working age people across the developed world, which is baked in and cannot be changed quickly given it takes 18 years to make a worker, has helped to usher in an era of lower growth (the formula for growth is very simple, it’s the number of workers times how much they produce. If the number of workers goes down, you have to improve productivity if growth is to be sustained). While most commentators refer disparagingly to Japan’s decades of low growth as an example of what must be avoided, he argued it’s a miracle Japan has managed to grow at all give its demographic challenges, and the fact it has is testimony to what fiscal spending can achieve.

As to whether China can sustain its growth rate, he reckons the key is to improve the productivity of the services sector, which is now 52% of GDP. China’s industrial sector’s productivity is world class, but services productivity is about 30% below world’s best practice. In his view the solution is simple: open China’s market to more international service companies so they can learn from them. Interestingly, we heard from Dr Weng Mingbo, the Deputy Secretary General of the Shanghai Municipal Government, that Shanghai had issued 1600 new licences to financial services firms in 2019.

When asked about inflation, they tacitly acknowledged that, the thing is, we don’t really know what causes inflation to rise and fall; all the old models have had to be rethought, so it could very well return at any time, though each indicated they don’t see that being the case. Dr Dudley said he’d been surprised that US wages growth hadn’t been stronger given unemployment is at 50-year lows (there goes the Phillips Curve?), but he expects it will happen at some point and that could underwrite higher inflation. Dr Rajan responded that for a long time many economists argued inflation was led by expectations, that is, if people expect prices will rise it becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. But, once again, Japan was referenced as dispelling that myth and could serve as a leading indicator.

Again, all three of the central bankers agreed that inflation is more of a mystery than we’d thought, and Dr Dudley said the Fed is giving thought to changing to targeting a range of, say, 1.5-2% per annum, or an average of 2% over the a cycle. Both would be subtle but significant changes, quietly admitting central banks cannot control inflation with any level of precision (again, the Japanese example was raised where the Bank of Japan has failed to reach every inflation target it’s set itself over the past 20 years despite throwing everything but the proverbial kitchen sink at it).

One final interesting point from Dr Dudley, he reminded us that everyone tends to presume the next recession will look just like the last one, but it rarely ever does.

Frankly, there was less focus on the current trade war between China and the US than I’d expected. That’s not to say people were dismissive, but it certainly didn’t dominate conversations and my sense was it’s been going long enough that we’ve probably reached the point of fatigue. Several speakers, including the central bankers, mentioned the level of uncertainty created by President Trump’s unpredictability, where a random tweet could change the course of things without warning, and while we all know markets don’t like uncertainty, there comes a point where it becomes the status quo.

Those who attended last year’s conference said the Chinese message then was ‘we’ve got to work this trade war out’, whereas this year the only dedicated session, which included Madam Fu Ying, a former Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, saw a more assertive Chinese stance. Madam Fu more or less said it’s pleasing the two governments are finding areas of agreement, as evidenced by the ‘Phase 1’ deal that’s just been signed, but if the US wants the benefits of leadership then it has to lead.

Dr Barry Naughton, Chair of Chinese Studies at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UCLA, all but admitted the US had underestimated the ramifications of China’s rise when he used the analogy that when China was admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001 it was like they had a pet baby tiger they could leave the kids to play with, and they’ve come back almost 20 years later to find they have a full grown tiger on their hands.

Madam Fu said the Chinese feel the US doesn’t want China to grow and the US needs to find ways to reassure them that’s not the case, meanwhile, Dr Naughton said the US feels confused because it appears China wants to supplant the US rather than work with them.

It was Dr Rajan that raised some interesting potential consequences that could arise if a resolution or compromise isn’t found: it’s conceivable there could be a split in key areas of technology where two distinct standards develop, one Chinese sponsored the other US. That potentially means countries could be forced to choose, which then becomes a question that carries both political and commercial significance, and if that’s about something as important as, say, 5G, there could be far reaching consequences. What if the US 5G standards are inferior to China’s or years behind, where does that leave a country like Australia?

Every presentation I listened to included references to climate change and explicit acknowledgement of the effects it’s already having, but also the necessity of addressing it and what the consequences might be from doing so. It was clear the Chinese government sees it as a really big deal, or at least they talk like they do, with climate change strategies incorporated into the government’s five-year plans.

One panel discussion included Dr Li Junfeng, the First Director General of the National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, who took a reasonably pragmatic approach saying China appreciates the economic challenge of transitioning away from fossil fuels, nevertheless it has set a goal of 75% renewable energy by 2050, from about 24% currently (much of which is hydro).

In terms of practical steps China is taking, it has the most electric vehicles in the world and accounts for some 90% of global production and it’s the biggest producer of PV panels and is embracing wind power too. There were signs of the commitment to its climate change strategy around Shanghai, with lots of EV’s on the road (they don’t have to pay annual licence fees) and electric Vespa-style scooters just everywhere (I saw one, admittedly far more utilitarian in its styling than a Vespa, selling for about $300 brand new).

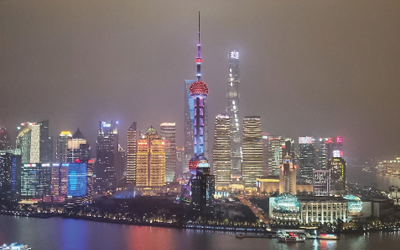

Possibly the biggest thing that struck me was the ‘can do-ness’ of China, thanks largely to the benefit of having an autocratic government that doesn’t have to worry about being re-elected. For example, the area on the far side of the river in the photo below, which is the iconic shot of the Pudong area of Shanghai, was rice fields 30 years ago. One of the delegates, who used to work in Hong Kong, told me he’d been at a conference in Shanghai around 1990 and a government official discussed their plans to turn those rice fields into a city over the following five years. He said he laughed at the suggestion, only to find five years later the area was covered in plain, rectangular skyscrapers. What you see in the photo is, in fact, the second generation of buildings on the site, and it is now Shanghai’s financial district, boasting, amongst other things, the second highest tower in the world.

While the Australian government frets about ‘picking winners’ to back, and consequently resorts to ‘letting the market decide’, the Chinese government picks industries it wants to lead the world in and backs them with the full resources of the State. Thus, years ago a struggling IT company called Huawei was picked as the Chinese 5G champion and now leads the world (yes, with all the attendant controversy). While climate change was probably the single most mentioned topic at the conference, with possibly the trade war second, the advent of 5G and the implications for tech industries would have been next.

Dr Chen, of the Shanghai Municipal Government, explained they had installed 14,000 5G stations around Shanghai in a single year, with plans to accelerate that. They had also built Tesla’s new mega-factory in 12 months and the first cars have been rolling off it recently. The next target is to establish Shanghai as one of the world’s leading financial centres, thus the 1,600 new licences mentioned before. Already, Shanghai’s stock market is the fourth biggest in the world at US$4 trillion, but Hong Kong is number five at US$3.9 trillion and Shenzhen is eighth at US$2.5 trillion. If you add them together, the Chinese markets are worth a combined US$10.4 trillion, which would put it second behind the US (which admittedly dwarfs it, for now, at US$33.7 trillion for the NASDAQ and NYSE combined).

Obviously there are dark sides to the Chinese government as well. It’s confronting not to be able to pick up your phone and Google something at will and watching the BBC or CNN news involves any story on China simply disappearing from the screen. The surveillance is frightening, and what’s happening to the Uighurs is simply appalling, and the Wall Street Journal reported this week that it estimates the Chinese government has given Huawei some US$75 billion worth of subsidies, tax breaks and benefits.

Clearly there’s no way western democratic companies can compete without significant state support as well, which involves overcoming the established neo-liberal doctrine that governments should keep out of the way of the market. No doubt this will continue to be an issue for a long time to come.

One final thing I learned: I went on a guided walk of Old Shanghai, a feature of which was seeing the 400-year-old home of Madam Goh, which was on 2,300 square metres of land. The buildings are in ruins and the government has been negotiating with Madam Goh’s family for years to buy it off them. Bear in mind, this part of Shanghai is so crowded I saw an ad to rent out 4 square metres of space for about A$265 per month! I said to the guide I’d have thought the Chinese government would have just said ‘We’re taking your land’, but she looked quite shocked at the suggestion and explained the government recognises her family owns the land and they need to compensate her accordingly. Like everything though, it’s a matter of reaching agreement as to what it’s worth.

There was, of course, plenty more covered at the conference, including plenty on the financial outlook for China. Overall, I came away with a stronger conviction that China’s influence on the world is only going to grow and western companies and governments need to take notice of what can be achieved with proper government support. I’m far from starry-eyed about how that growth has been achieved in terms of the consequences for personal liberties and the environmental effects, but from a pragmatic point of view the China story is a long, long way from over.

Conventional economics is having a really hard time explaining what’s going on in much of the world today: how can we have such low inflation when interest rates are at record low levels? How can some governments consistently run deficits, that look for all the world like they could never be repaid, and yet their bond yields are going down, not up? How come those economies where central banks have been pumping in stimulus for years, are still showing sluggish rates of growth?

The same questions have left many investors perplexed as asset prices stay high while they read about a range of risks.

It makes sense that if conventional thinking can’t explain what’s going on, then it’s time to look elsewhere. There is one school of economic thought that’s been talking about the inevitability of declining inflation and interest rates for years. It has not just a plausible, but also logical, explanation for many of the conundrums that leave orthodox economists scratching their heads.

However, that school of thought is so unconventional, and requires such a radical change to long-accepted wisdom, that those orthodox economists, including some of the best known names in the industry, have been lining up to ridicule it. But the most common criticisms sometimes show at best a lack of understanding, and at worst, an unwillingness to think differently.

That new school of thought is known as Modern Monetary Theory, which is commonly abbreviated to MMT. The first problem MMT has is its name, which is simply not a good description of what it is.

While it is indeed modern, having been developed in the early 1990s, it could easily be mistaken as a new version of ‘monetarism’, which was the economic theory developed by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School back in the 1960s that advocated, amongst other things, that markets are best at determining the optimal allocation of resources, so the role of government should be minimised and indeed fiscal spending is not only ineffective but irresponsible, because the resulting government borrowing will end up increasing interest rates, inflationary expectations, or future taxation in order to fund it.

But if that thinking’s right, then how is it that Japan and the US, both with massive government deficits, can reduce tax rates and have falling inflation and interest rates?

MMT is, in fact, the antithesis of monetarism, arguing governments must spend in order to achieve full utilisation of an economy’s resources. In that sense, it’s closer to Keynesianism. Finally, it’s not really a ‘theory’, it’s actually a straight up application of accounting rules to explain how money works in an economy where the government controls its own currency, in other words, an economy like Australia’s.

One of MMT’s most controversial insights is that such a government cannot be insolvent, that is, it can never run out of money, however, it can go broke. How that works is a government creates brand new money whenever it injects more in fiscal policy that it takes back in taxes, so, by logical extension, it can never run out.

However, that money is effectively backed by all the resources of the economy: all the workers, machines, factories and farms. If every single one of the workers suddenly disappeared, so there’s nobody left to run the machines, then the economy’s stuffed and the money is worthless. The government would be broke.

In this sense, one of the hardest lessons to get your head around that MMT teaches us, is that treating a government like it’s a household is fundamentally wrong. A household doesn’t control its own currency, so it can easily become both insolvent and broke. If a household spends more than it earns, or takes on too much debt, it’s in big trouble.

Because a government can create money at will, MMT points out that government spending is not constrained by a lack of funds. This is where conventional economists yell indignantly that MMT is preposterous: telling a government it can spend as much as it wants is a sure-fire recipe for inflationary disaster, and they’ll often refer to Venezuela, Zimbabwe or the Weimar Republic of the 1930s as examples of what happens when governments spend money as if there were no limits.

But MMT explicitly acknowledges the existence and risks of government deficits and inflation. What it says though, in a very simplified example, is imagine the economy is like a giant department store where both the private sector and the government sector shop for the things they need, everything from hospitals, to cars, workers, or soldiers. If some of the stock is not being bought by the private sector, that means there’s excess capacity and you’d expect prices will not be rising. It follows the government is able to go to the store and keep buying things with its printed money until all the stuff in the shop is being sold before you’d expect prices to rise.

One of the critical things to remember about MMT is it’s not a policy framework, it’s simply a model of how money works in a modern economy and this has been a very brief and basic overview of what is a complex and sophisticated body of work that’s gaining increasing traction as the most logical explanation of a variety of situations that conventional economics is at a loss to explain.

In the first part of this overview of Modern Monetary Theory, I suggested it provides the most logical explanation of what’s going on in the world’s economies that conventional economics is simply at a loss to account for.

One of the unexplained mysteries is how countries can have the lowest interest rates in history, which is supposed to stimulate the economy, with low unemployment and yet economic growth is also, surprisingly, low.

Back in the early 1980s the US central bank ‘put the inflation genie back in the bottle’ by cranking interest rates all the way to 20%. Soon after that, governments the world over happily passed responsibility for managing economic growth to their central banks in the form of targeted inflation and unemployment rates.

The problem is, central banks only have one weapon: short-term interest rates, also known as the cash rate. In an effort to stimulate growth over the past almost 40 years, central banks have been steadily reducing interest rates. Occasionally they’ve had to raise them when lending growth got out of hand, but the overall trend has been a steady decline.

The other side of this story is governments at the same time tried to minimise budget deficits, on the basis that conventional economic theory dictates it’s prudent economic management. However, another of MMT’s insights is that government spending creates money and activity. When a government spends more than it takes back in taxes, referred to as a budget deficit, it’s injecting money into the economy. But when it runs a budget surplus, it’s sucking money out of the economy, meaning the only way for the economy to grow is by the private sector making up for the reduction of government money in the system by running down their savings and borrowing money.

Here in Australia, the Howard government was lauded for running budget surpluses, so how did the economy grow so strongly over that period? In short, there was a credit boom. Household savings rates fell from 4% to -1%, and credit growth averaged around 12%, peaking as high as 16% in 2005. The result was household debt increased from around $200 billion to $900 billion, representing an almighty credit impulse to offset the lack of government spending.

MMT identified ages ago that relying on households to borrow in order to stimulate the economy will only work for so long, because eventually borrowing capacity maxes out and you’re left with the situation we have now, rates are the lowest they’ve ever been but credit growth is also the lowest since they started tracking it in 1977. Economists call it ‘pushing on a string’.

Not surprisingly, Philip Lowe, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, has been all but begging the government to crank up fiscal spending in order to support the economy. And he’s not the only one, central bankers across the world, acknowledging that monetary policy has reached the end game, have been calling on governments to start doing some of the heavy lifting by increasing fiscal spending.

The problem is politicians are stuck in the conventional economic mindset that presumes a government’s finances are the same as a household’s, which we learned above is fundamentally wrong, since a household cannot print its own money. A government that can print its own money is never financially constrained.

MMT does, however, acknowledge that a government is constrained by its economy’s total resources. Once government spending hits a level where it’s competing against private spending, prices will go up and inflation sets in.

Until that point, though, accumulated government deficits simply represent money the government has put into the economy that hasn’t been taken back out again by taxes. Another of MMT’s insights that conventional economists find hard to swallow, is that accumulated deficits don’t represent a burden on future generations that will result in crushing interest rates or catastrophically weak currencies as overseas investors refuse to fund our indulgent spending.

The best illustration of that is Japan, where government debt is 240% of GDP. As remarkable as it is, the government could print a ¥1,000,000,000,000,000 (that’s one quadrillion) yen note tomorrow and the debt will be instantly extinguished. Ah, but, the conventional economists scream, no one would ever trust the Japanese government again. Realistically, no one expects the government to repay that debt, ever, and it’s going up at about ¥1 million every two seconds! And yet the world continues to trade with Japan, the Yen is seen as a ‘safe haven’ currency and inflation has averaged around 0% for the last 25 years.

While MMT asserts government spending is not financially constrained, it also acknowledges some government spending is better than others. A big chunk of President Trump’s US$1.5 trillion of tax cuts went into the pockets of people who were already net savers, so the growth benefit was muted. That same US$1.5 trillion could have been used to eliminate student debt and almost all the money would have gone into the pockets of people who are net spenders, so the growth impact would have been far more pronounced.

Similarly, governments can spend on infrastructure, education, promoting R&D, or improving health, all things that underwrite long-term growth.

MMT uses iron clad rules of accounting to describe how government finances work, which is a such a radically different approach to conventional wisdom that it is understandably meeting stiff resistance, but if conventional thinking can’t explain what’s going on, then clearly it’s time to think unconventionally. With Australian households unable, or unwilling, to take on more debt to underwrite economic growth, and the Morrison government doggedly insisting it will deliver a budget surplus, the MMT school would be suggesting that does not auger well for a bright near-term outlook.