(notes from a conference)

For fear of sounding like a real nerd, anyone even remotely interested in financial markets will appreciate how exciting it is to have an audience with three international central bankers. I got that opportunity, amongst other things, this week at the twentieth anniversary of UBS’s Greater China Conference, held in Shanghai over Monday and Tuesday.

It was my first time in China, and while suggesting Shanghai is representative of China is like saying the same thing about Sydney and Australia, I did come away with a changed impression and understanding of the country; but I’ll come back to that, first the exciting stuff.

‘The new normal for the global economy’

Full credit to UBS that they were able to get three rock star central bankers for this presentation: Dr Bill Dudley is the President of the New York Federal Reserve, Dr Raghuram Rajan was the 23rd Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and the former Chief Economist and Director of Research at the IMF, and Dr Min Zhu is a former Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China. One thing to bear in mind, however, while these guys are super smart and extraordinarily well connected, they don’t possess a working crystal ball and what they say is still a (very well informed) best guess.

Their respective views of the ‘new normal’ were extremely close to each other: an ongoing environment of slow growth, low unemployment and low inflation – in other words, no meaningful change from what we’ve experienced over much of the past 10 years. Given the similarity of their outlooks, I can only presume that, for now at least, they don’t see anything on the horizon that’s going to cause things to change much.

To me, the most interesting part of Dr Dudley’s message was his candid acknowledgement that if interest rates are as low as they are now when the next recession hits, there’s obviously not much room to cut them in order to support a recovery. While he acknowledged central banks do have other (read unconventional) tools at their disposal, such as quantitative easing, he argued monetary policy alone will not be sufficient to pull the economy out of recession and reiterated several times they will definitely need fiscal policy, so changes in government spending, to do some, if not a lot, of the heavy lifting.

That is an identical position to most central bankers, including Australia’s Dr Philip Lowe, who have collectively been saying that monetary policy is reaching the limits of what it can do and have been pleading with governments to open their wallets and spend. Dr Rajan also said that while unemployment is very low across the world, job dissatisfaction is relatively high because the quality of a lot of those jobs is poor, and this is something fiscal policy is far better placed to address than monetary policy.

Importantly, and as you’d expect, Dr Dudley also stuck with the Fed’s current script that they are in no hurry at all to raise rates, and will be happy to let inflation in the US run above its 2% target level before they increase from the current 1.75%. That sits well with the market’s current view of where interest rates are headed and is considerably more optimistic than UBS’s US Chief Economist, who spent 14 years at the Fed, and is forecasting three rate cuts this year in response to a weakening economy.

Dr Rajan gave his rundown of what he considers to be the five major influences on economies, none of which will surprise anyone:

- Technological innovation, which is increasing productivity but is also changing the nature of jobs that are available to those without higher education

- Demographics, which he sees as presenting threats and opportunities

- The rise of emerging nations and the need to find ways of accommodating their growth and aspirations

- Inequality, which underpins the rise of populist politics

- Climate change, which he also sees as presenting threats and opportunities.

Dr Min commented that all technological change is disruptive to the extent that it usually means an existing system is changed in favour of the new, and he pointed to the possibilities that 5G brings with the ‘internet of things’. It took China five years to reach some 3.7 billion 4G devices and it’s targeting all of those to be switched to 5G within 2.5 years, bringing with it the benefits of bigger, faster, fatter pipes of data.

He also believes that ageing demographics and the gradual reduction in the proportion of working age people across the developed world, which is baked in and cannot be changed quickly given it takes 18 years to make a worker, has helped to usher in an era of lower growth (the formula for growth is very simple, it’s the number of workers times how much they produce. If the number of workers goes down, you have to improve productivity if growth is to be sustained). While most commentators refer disparagingly to Japan’s decades of low growth as an example of what must be avoided, he argued it’s a miracle Japan has managed to grow at all give its demographic challenges, and the fact it has is testimony to what fiscal spending can achieve.

As to whether China can sustain its growth rate, he reckons the key is to improve the productivity of the services sector, which is now 52% of GDP. China’s industrial sector’s productivity is world class, but services productivity is about 30% below world’s best practice. In his view the solution is simple: open China’s market to more international service companies so they can learn from them. Interestingly, we heard from Dr Weng Mingbo, the Deputy Secretary General of the Shanghai Municipal Government, that Shanghai had issued 1600 new licences to financial services firms in 2019.

When asked about inflation, they tacitly acknowledged that, the thing is, we don’t really know what causes inflation to rise and fall; all the old models have had to be rethought, so it could very well return at any time, though each indicated they don’t see that being the case. Dr Dudley said he’d been surprised that US wages growth hadn’t been stronger given unemployment is at 50-year lows (there goes the Phillips Curve?), but he expects it will happen at some point and that could underwrite higher inflation. Dr Rajan responded that for a long time many economists argued inflation was led by expectations, that is, if people expect prices will rise it becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. But, once again, Japan was referenced as dispelling that myth and could serve as a leading indicator.

Again, all three of the central bankers agreed that inflation is more of a mystery than we’d thought, and Dr Dudley said the Fed is giving thought to changing to targeting a range of, say, 1.5-2% per annum, or an average of 2% over the a cycle. Both would be subtle but significant changes, quietly admitting central banks cannot control inflation with any level of precision (again, the Japanese example was raised where the Bank of Japan has failed to reach every inflation target it’s set itself over the past 20 years despite throwing everything but the proverbial kitchen sink at it).

One final interesting point from Dr Dudley, he reminded us that everyone tends to presume the next recession will look just like the last one, but it rarely ever does.

The trade war

Frankly, there was less focus on the current trade war between China and the US than I’d expected. That’s not to say people were dismissive, but it certainly didn’t dominate conversations and my sense was it’s been going long enough that we’ve probably reached the point of fatigue. Several speakers, including the central bankers, mentioned the level of uncertainty created by President Trump’s unpredictability, where a random tweet could change the course of things without warning, and while we all know markets don’t like uncertainty, there comes a point where it becomes the status quo.

Those who attended last year’s conference said the Chinese message then was ‘we’ve got to work this trade war out’, whereas this year the only dedicated session, which included Madam Fu Ying, a former Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, saw a more assertive Chinese stance. Madam Fu more or less said it’s pleasing the two governments are finding areas of agreement, as evidenced by the ‘Phase 1’ deal that’s just been signed, but if the US wants the benefits of leadership then it has to lead.

Dr Barry Naughton, Chair of Chinese Studies at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UCLA, all but admitted the US had underestimated the ramifications of China’s rise when he used the analogy that when China was admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001 it was like they had a pet baby tiger they could leave the kids to play with, and they’ve come back almost 20 years later to find they have a full grown tiger on their hands.

Madam Fu said the Chinese feel the US doesn’t want China to grow and the US needs to find ways to reassure them that’s not the case, meanwhile, Dr Naughton said the US feels confused because it appears China wants to supplant the US rather than work with them.

It was Dr Rajan that raised some interesting potential consequences that could arise if a resolution or compromise isn’t found: it’s conceivable there could be a split in key areas of technology where two distinct standards develop, one Chinese sponsored the other US. That potentially means countries could be forced to choose, which then becomes a question that carries both political and commercial significance, and if that’s about something as important as, say, 5G, there could be far reaching consequences. What if the US 5G standards are inferior to China’s or years behind, where does that leave a country like Australia?

Climate change

Every presentation I listened to included references to climate change and explicit acknowledgement of the effects it’s already having, but also the necessity of addressing it and what the consequences might be from doing so. It was clear the Chinese government sees it as a really big deal, or at least they talk like they do, with climate change strategies incorporated into the government’s five-year plans.

One panel discussion included Dr Li Junfeng, the First Director General of the National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, who took a reasonably pragmatic approach saying China appreciates the economic challenge of transitioning away from fossil fuels, nevertheless it has set a goal of 75% renewable energy by 2050, from about 24% currently (much of which is hydro).

In terms of practical steps China is taking, it has the most electric vehicles in the world and accounts for some 90% of global production and it’s the biggest producer of PV panels and is embracing wind power too. There were signs of the commitment to its climate change strategy around Shanghai, with lots of EV’s on the road (they don’t have to pay annual licence fees) and electric Vespa-style scooters just everywhere (I saw one, admittedly far more utilitarian in its styling than a Vespa, selling for about $300 brand new).

Other observations

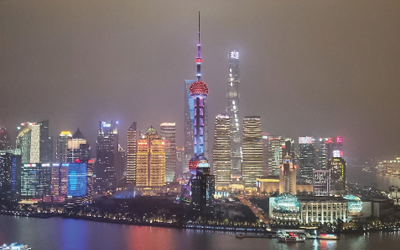

Possibly the biggest thing that struck me was the ‘can do-ness’ of China, thanks largely to the benefit of having an autocratic government that doesn’t have to worry about being re-elected. For example, the area on the far side of the river in the photo below, which is the iconic shot of the Pudong area of Shanghai, was rice fields 30 years ago. One of the delegates, who used to work in Hong Kong, told me he’d been at a conference in Shanghai around 1990 and a government official discussed their plans to turn those rice fields into a city over the following five years. He said he laughed at the suggestion, only to find five years later the area was covered in plain, rectangular skyscrapers. What you see in the photo is, in fact, the second generation of buildings on the site, and it is now Shanghai’s financial district, boasting, amongst other things, the second highest tower in the world.

Shanghai’s Pudong financial district – it was all rice paddies 30 years ago

While the Australian government frets about ‘picking winners’ to back, and consequently resorts to ‘letting the market decide’, the Chinese government picks industries it wants to lead the world in and backs them with the full resources of the State. Thus, years ago a struggling IT company called Huawei was picked as the Chinese 5G champion and now leads the world (yes, with all the attendant controversy). While climate change was probably the single most mentioned topic at the conference, with possibly the trade war second, the advent of 5G and the implications for tech industries would have been next.

Dr Chen, of the Shanghai Municipal Government, explained they had installed 14,000 5G stations around Shanghai in a single year, with plans to accelerate that. They had also built Tesla’s new mega-factory in 12 months and the first cars have been rolling off it recently. The next target is to establish Shanghai as one of the world’s leading financial centres, thus the 1,600 new licences mentioned before. Already, Shanghai’s stock market is the fourth biggest in the world at US$4 trillion, but Hong Kong is number five at US$3.9 trillion and Shenzhen is eighth at US$2.5 trillion. If you add them together, the Chinese markets are worth a combined US$10.4 trillion, which would put it second behind the US (which admittedly dwarfs it, for now, at US$33.7 trillion for the NASDAQ and NYSE combined).

Obviously there are dark sides to the Chinese government as well. It’s confronting not to be able to pick up your phone and Google something at will and watching the BBC or CNN news involves any story on China simply disappearing from the screen. The surveillance is frightening, and what’s happening to the Uighurs is simply appalling, and the Wall Street Journal reported this week that it estimates the Chinese government has given Huawei some US$75 billion worth of subsidies, tax breaks and benefits.

Clearly there’s no way western democratic companies can compete without significant state support as well, which involves overcoming the established neo-liberal doctrine that governments should keep out of the way of the market. No doubt this will continue to be an issue for a long time to come.

One final thing I learned: I went on a guided walk of Old Shanghai, a feature of which was seeing the 400-year-old home of Madam Goh, which was on 2,300 square metres of land. The buildings are in ruins and the government has been negotiating with Madam Goh’s family for years to buy it off them. Bear in mind, this part of Shanghai is so crowded I saw an ad to rent out 4 square metres of space for about A$265 per month! I said to the guide I’d have thought the Chinese government would have just said ‘We’re taking your land’, but she looked quite shocked at the suggestion and explained the government recognises her family owns the land and they need to compensate her accordingly. Like everything though, it’s a matter of reaching agreement as to what it’s worth.

Conclusion

There was, of course, plenty more covered at the conference, including plenty on the financial outlook for China. Overall, I came away with a stronger conviction that China’s influence on the world is only going to grow and western companies and governments need to take notice of what can be achieved with proper government support. I’m far from starry-eyed about how that growth has been achieved in terms of the consequences for personal liberties and the environmental effects, but from a pragmatic point of view the China story is a long, long way from over.