Addressing inequality would be good for the whole economy

Inequality of incomes and wealth continues to be a well-deserved point of focus across the developed world. The US produces the best data, and by 2016 the top 1% of households held 29% of the country’s wealth, while the entire middle class owned 21% and real median income has fallen over the past 40 years. This inequality of wealth and income is actually reducing growth for the overall economy.

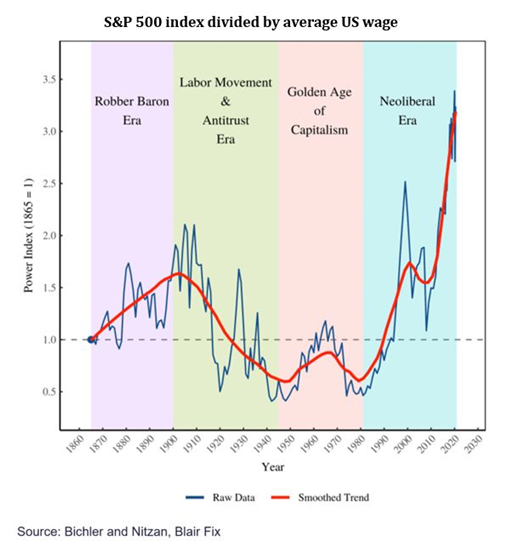

The chart below uses a simple, but insightful, method to argue inequality really took root under the ‘neo-liberal’ economic era. If it’s correct, that premise throws up some suggestions as to how it can be addressed.

First, what is the chart telling us? It effectively traces the relative strength of labour versus capital. When the line is trending upwards, share prices, as measured by the US’s S&P 500, are rising faster than the average wage. That means there is a greater share of the economic pie going to the owners of capital than to labour.

After WW2 the US became the world’s factory and there was a relative scarcity of workers, so wages were strong. The next bottom in the chart, around the 1970s, was when unions were throwing their weight around and the US and UK lost a record number of days to strikes. Wages were commonly indexed to inflation, which created the classic wage-price spiral: as wages rose, so did prices, which again caused wages to rise, and so on.

Then came the era of Thatcher and Reagan, and the wholehearted embrace of neo-liberalism. This philosophy, which was largely founded on the work of Milton Friedman, argued markets are best at determining the allocation of resources so the best thing governments can do is get out of their way. It coincided with the crushing of unions, and the highest interest rates ever recorded as central banks around the world followed the US Fed Chairman, Paul Volcker, in his efforts to stomp out inflation.

Neo-liberalism is also called ‘supply side economics’, the premise of which is that reducing regulation and government interference would enable markets to flourish and encourage economic growth, and the benefits of all that growth would trickle down and be shared broadly. Indeed, Paul Volcker predicted that “wages for all Americans will improve as we achieve greater productivity and moderation in the demand for nominal wage increases.”

Well, that hasn’t happened. In his terrific book, The Economists’ Hour, Binymain Applebaum writes that “the median income of a full-time male worker in 1978, adjusted for inflation, was $54,392. That number was not matched or exceeded at any point in the next four decades. As of 2017, the most recent available data, the median income of a full-time male worker was $52,146. Yet, over those same four decades, the nation’s annual economic output, adjusted for inflation, roughly tripled.”

Likewise, economist Thomas Piketty argues that, in fact, the whole of the US is worse off under the neo-liberal model: between 1910-1950 national income per capita grew at 2.1% per year, from 1950-1990 it was 2.2%, and 1990-2020 only 1.1%.

In other words, as income and wealth inequality has worsened, so too has overall economic prosperity.

The solution? On the face of it, economies would be collectively better off if there was some equalisation of power between labour and capital. It also suggests there is indeed a role for government in areas like regulating labour markets and controlling corporate power.