March 2021 quarterly outlook

Welcome to our Steward Wealth quarterly outlook video, a brief overview of where we see markets now and how we’re positioned.

Welcome to our Steward Wealth quarterly outlook video, a brief overview of where we see markets now and how we’re positioned.

Jeremy Grantham is the legendary former Chief Strategist of fund manager GMO. In his 82 years there’s very little he hasn’t seen in financial markets, and he rightly earned his legend status by calling the last three great stock market bubbles: the Japanese equities bubble of the late 1980s, the US dotcom bubble at the end of the 1990s and the 2008 GFC.

So it’s understandable people took notice when he greeted the new year with a frightening declaration:

The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully-fledged epic bubble. Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases, frenzied issuance, and hysterically speculative investor behaviour, I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Sea bubble, 1929, and 2000.

It sounds absurdly presumptuous to take the other side against such a storied investor, but I believe Grantham’s arguments warrant some context, and smart investors should always consider the counter factual.

First, Grantham has warned of an imminent US stock market collapse literally every year since the GFC and always for the same reasons: over extended valuations and the market’s reliance on central bank support. Grantham made a career out of identifying stock market bubbles, but even he conceded in an interview with Barron’s in 2015 that “for bubble historians…it is tempting to see them too often.”

Second, Grantham points to the S&P 500’s PE being in the top few per cent of its historical range while the economy is in the worst few.

With respect to the PE ratio, there have been spectacular changes in the macro, or big picture, settings for stock markets that have dramatically affected valuations. For example, inflation and interest rates have undergone the greatest ever reversal over the past 40 years. After interest rates peaked at close to 20 per cent under Fed President Volcker in the early 1980s, they have drifted lower and lower ever since, to the point where now we are becoming accustomed to negative government bond yields. Likewise, inflation is persistently below central bank targets.

I’ve argued before that it makes perfect sense those low yields have a profound influence on how shares are valued, especially for companies that offer higher levels of growth than the broader market. Whether it be through basing a discounted cash flow valuation on lower risk-free rates (bond yields) or the return premium offered by stocks over bonds, lower yields drive higher share prices.

Given we’ve never seen a mix of yields and inflation like we’re seeing now, using historical references as your only valuation anchor makes no sense. A more convincing concern is the potential return of inflation because that will fundamentally change the valuation landscape, but there is no one who can give you a definitive answer as to what drives inflation. You need only look at the Fed’s ‘dot plot’, which started back in 2012 and records where each of its 12 board members and seven presidents think inflation and interest rates are headed. Despite having the best information available, and apparently being the best qualified in the US, they’ve never been close to right.

Another thing that has driven valuations on the US market up is that so-called ‘growth’ stocks, which are those companies whose earnings are growing faster than the index and therefore usually trade on higher PE ratios, have increased from 15 per cent of the overall index in the 1970s to now 77 per cent. By contrast, ‘value’ stocks, which rely more on general levels of economic growth and trade on lower PEs, account for commensurately less of the index.

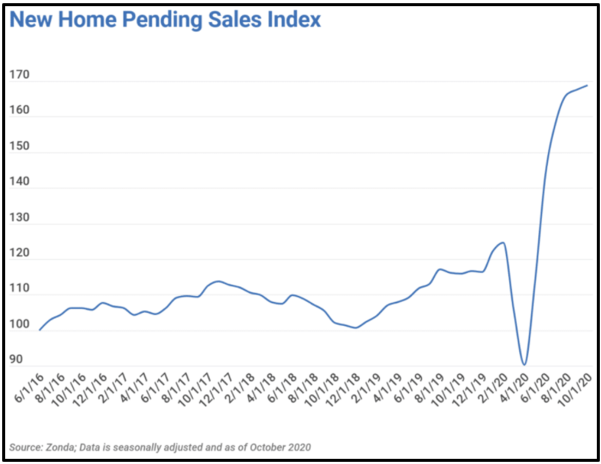

In terms of the economy being terrible, recent economic data suggests otherwise. Like Australia, the US government injected about 13 per cent of GDP in brand new money in the form of COVID support, money that has to go somewhere. Sure, GDP fell 31 per cent in the March quarter of 2020, but it rocketed up 33 per cent in the June quarter. Business confidence is close to its equal highest in the last 25 years, unemployment is not far off its average for the post GFC/pre-COVID period, house prices are at an all-time high and there has been a record number of US companies upgrading earnings guidance in the first quarter. And the new Biden administration is preparing to spend another $1.9 trillion.

By his own admission, Grantham’s past calls have typically been early. Getting out of Japanese and US stocks two years before the market peak cost his firm’s investors about 60 per cent each time. That offers a couple of salutary lessons. First, timing market tops is really challenging, especially if you rely on valuations to do it. And second, even if you’re worried about a market looking toppy, you don’t have to sell out of it entirely. You can simply reduce your holding gradually as it rises and switch your money into an asset class or market that doesn’t look as stretched, such as Australian, European or emerging markets shares.

There are undoubtedly pockets of the US market that look extreme right now, especially the speculative end of retail investors, but even that doesn’t apply to the whole market. When billionaires make bearish calls it’s hard to overcome our innate human bias that prioritises self-preservation and sees pessimists as smarter, but for your portfolio’s sake, it can pay to look for context.

Welcome to our Steward Wealth quarterly outlook video, a brief overview of where we see markets now and how we’re positioned.

There are number of things that make the global economic recession of 2020 different to any other we’ve seen, and while you’d never wish to go through an experience like it, there are definitely some silver linings.

This was the first time in living memory that governments deliberately threw economies into recession. If you close down all but a few sectors and tell workers to stay home, obviously economic activity is going to crash.

Previous recessions have been attributable to the business cycle: typically there is a speculative build up which causes an imbalance that eventually tips over, and the worst recessions are those fueled by debt.

The standout example of this is, of course, the GFC. Building activity reached frenziewd levels in the US because buyers were able to access debt way too easily. The adjustment process was long and painful because credit, which is the lifeblood of a modern economy, all but seized up.

When a recession is caused by excess building in some part of the economy, there is normally going to be a culprit you can point to. It might be banks, or it might be investors, but there’s a group that cops the blame and derision for crashing the economy.

That’s when the philosophy of ‘moral hazard’ argues if the culprits just get bailed out there’s no lessons learned to stop the same thing from happening again. Politicians and the media will often argue the responsible group should somehow be punished, perhaps with tighter regulations or even criminal charges.

This time (ignoring arguments about how COVID started and who or what is responsible), there is no real culprit to punish.

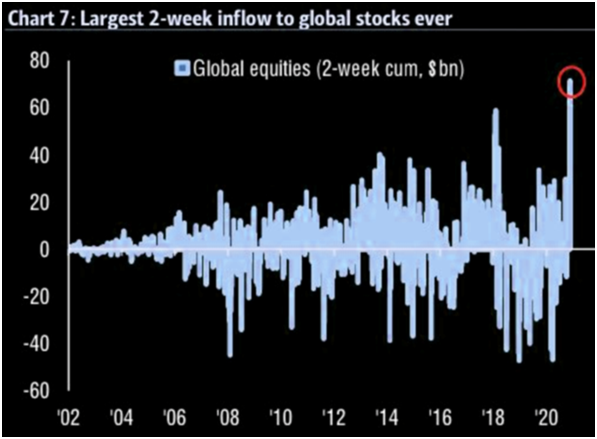

Because the government was responsible for switching off the economy and there was no concern about moral hazard, both they and central banks were able to throw the proverbial kitchen sink at supporting the economy.

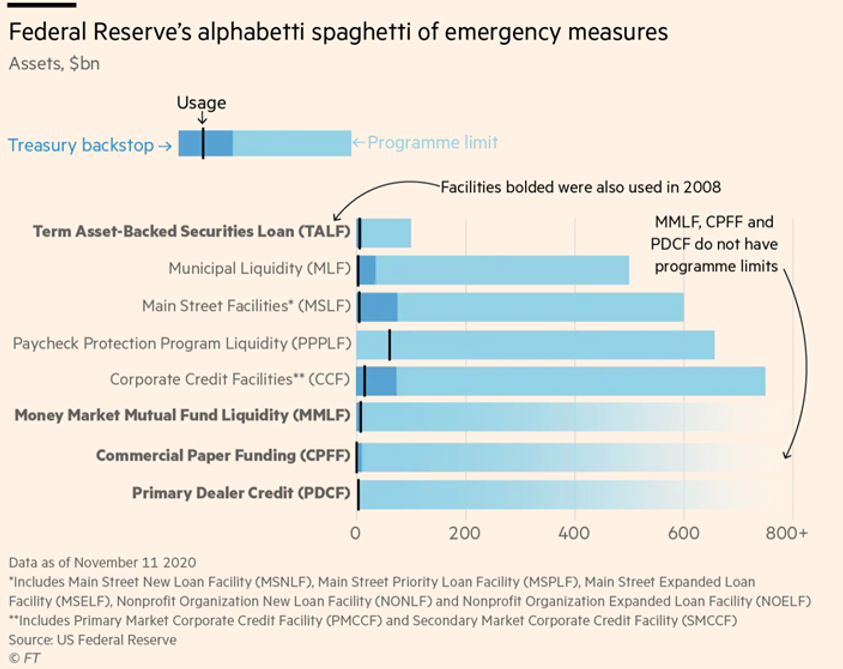

Central bankers learned valuable lessons from the GFC that they had to make sure credit could continue to flow. The range of measures undertaken was unlike anything we’d seen before, and while things were ugly for a short time, markets were once again reminded how powerful central banks can be.

Remarkably, US financial markets have clearly recovered strongly despite the Federal Reserve barely tapping a range of the programs they announced – see chart 1 below.

By far the most important support measures were from governments. One after another, governments wre throwing massive amounts of newly created money into their economies. Programs like JobKeeper in Australia and its equivalents overseas were critical in supporting families that otherwise would have been in dire financial circumstances.

The critical part is that it was newly created money, which governments can do directly, but central banks can’t. The central bank programs can help create new money by encouraging people to borrow (loans also create money) but that was going to be tough when the media was full of stories about the global economy crashing.

This is the opposite to what happened after the GFC, where, especially in Europe, governments preached from the gospel of austerity. Spending cutbacks sucked money out of economies and saw them slow to a grinding crawl.

Some of the data showing how sharply economies are bouncing back is remarkable. Here in Australia, we’re seeing restaurant bookings up to 50-80% compared with the same time last year, new car sales leaped 12% from last year and Commonwealth Bank credit card sales were up 11%. They are huge numbers and it’s not just because lockdown restrictions were eased.

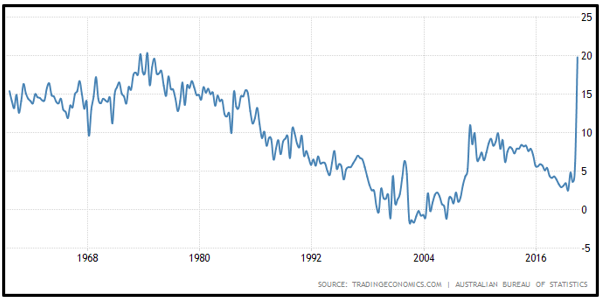

The Australian government’s COVID support programs amounted to 13% of GDP. It’s hard to overstate how massive that is. In the wake of the GFC, the Chinese government ‘rescued’ much of the developed world by announcing a spending package equivalent to 12% GDP (clearly the absolute amounts are hugely different, it’s the proportion that’s significant). The early withdrawal of superannuation adds anotehr 2% to that. The household savings ratio hit almost 20% in the June quarter, only a fraction less than the highest it’s been in the past 60 years.

That’s an awful lot of pent-up spending power.

Ever since the end of the GFC, central banks have pleaded with governments to raise fiscal spending to help increase economic growth. But most governments, including Australia’s, were obsessive about balancing budgets and instead were more intent on reducing spending (the obvious exception to that was $1.2 trillion Trump tax cuts, which helps explain why the US economy was doing so much better than most others).

It’s taken the unique circumstances of the pandemic to show the power of fiscal spending to drive economic activity: low income families suddenly had enough money to go to the dentist and get the car fixed, and the money they spent doing that got spent again and again.

If governments take the lessons on board, it’s possible it could be the first step toward abandoning the flawed dictums of neoliberalism and addressing the massive wealth inequalities that lie at the heart of so many other problems we face. That would be a great silver lining.

Call Steward Wealth today on (03) 9975 7070 to learn how.

While the indicators are stacking up well, there are, of course, no guarantees that markets will play ball and they sure do have a way of wrong-footing us. However, it’s noteworthy that nothing in the economy was ‘broken’ going into the pandemic downturn; there was no particular sector on the cusp of being crushed by excessive debt and while valuations were not cheap, they were certainly defensible.

Now is not the time to be sitting on lots of cash.