John D. Rockefeller, once the world’s wealthiest man, claimed that nothing gave him more pleasure than watching his dividends come in. Many Australian investors feel the same, giving rise to a popular strategy of investing in companies that pay high dividends that will hopefully fund the cost of living while preserving the underlying capital – that way you hopefully don’t outlive your savings.

While it seems like a conservative approach, the upheaval caused by the COVID19 lockdown has exposed the multiple risks of this strategy and should prompt those investors to consider the benefits of a different way of looking at how a portfolio can fund your lifestyle.

Reduced dividends = a pay cut

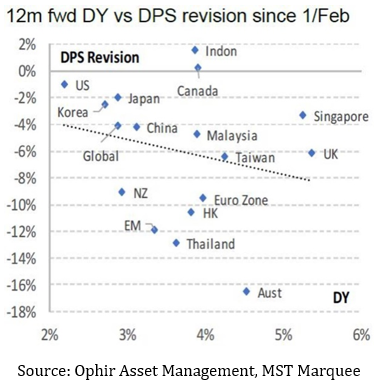

Leading Australian small cap fund manager, Ophir Asset Management, quotes research by MST Marquee that between the start of February and the end of April, Australian dividend forecasts suffered a 16% cut, the biggest in the world.

But there could be more to come. Will Baylis, a portfolio manager with equity income specialist Legg Mason Martin Currie, says the dividend forecasts published by stockbroking analysts have yet to fully account for the effect that slashed company earnings will have on dividends, with their own internal forecasts being more like a fall of 25% this year.

Risk #1: the wrong kind of stocks

Investing in high yielding shares can be a fabulous strategy, because not only have Australian dividends been relatively generous, but historically they’ve been reliable and consistent – if you pick the right ones. Baylis points out that dividends have grown at 3.9% per annum over the 10 years to the end of March this year, while over the same period term deposit rates have fallen by 17% per year.

The problem is that by just focusing on the dividend, rather than the whole story, many investors end up with shareholdings that destroy capital. The classic example of this is the major banks, which Australian investors have had a long love for, but which face some potentially strong headwinds, something I warned about last year.

If you’d invested $100,000 into each of the big four banks at the start of 2010 you’d have seen an overall return of 5.7% per year (including franking), but if you’d used all the dividends to fund your cost of living, you’d have had less than $320,000 of capital left by the end of April this year. The only bank to have delivered an increase in price was the Commonwealth Bank, by 14% (a measly compounded return of 1.3% per annum), the share prices of the other three banks fell by an average of 33%. Indeed, you may be surprised to know that at the end of February, so before the banks were hit by the COVID19 selloff, ANZ’s and Westpac’s prices were the same as they were 14 years ago, and NAB’s was the same as 20 years ago!

An alternative income strategy has been infrastructure, property and utilities shares, otherwise known as ‘real assets’, which generally have steady, predictable income streams and assets that are leveraged to a growing population. A simple portfolio invested equally between Transurban, Sydney Airport, Spark and the Vanguard Australian Property ETF over the same period would have seen your capital double, and a total average annual return of more than 10%.

A far better strategy is to focus on the total return from an investment, that is, dividends plus capital. CSL might be an extreme example, given how well it’s done, but those shares have always traded on a relatively paltry yield of 1-2%, but over that same 10-plus year period the total return was a phenomenal 25% per year, 94% of which was capital growth.

Risk #2: a lack of diversification

You might think investing entirely in high yielding, blue chip Australian shares is a conservative strategy, but there is no doubt, that is a high risk portfolio: the Australian share market has suffered falls of as much as 38% in a year, hardly conservative.

The best way to reduce risk in a portfolio is to make sure it’s diversified across a range of asset classes and geographies, a process called asset allocation, a basic principle of which is that different countries will perform differently over the same time frame. For example, over the 10 years to the end of March, US shares have delivered returns of 16% per year, more than double Australia’s.

Returns like that also put paid to the preoccupation some Australian investors have with capturing franking credits. It’s essential to focus on the bottom line: NAB’s dividends have been fully franked, but you’d have lost a whopping 38% of your capital over the past 10 years.

Also, you can cast your view beyond just shares. For example, investing in corporate bonds from across the globe offers a vast range of risk and return, some of which can be more predictable and, if managed correctly, less volatile than shares.

Take a dividend from your whole portfolio

Focusing on a total return strategy, rather than an income-oriented one, does require a slightly different mindset: rather than living off the dividends generated by your portfolio, you need to look at it as paying yourself a dividend from your overall portfolio, which can be funded through a combination of income and capital growth.

That might involve setting a certain dollar amount you harvest from your portfolio each year, or a percentage. Either way, it means you’ll need to rebalance your portfolio from time to time, a small and very healthy price to pay for heeding the COVID19 wake up call.