Simply voting out Donald Trump won’t do it, nor will a soft or hard Brexit. The underlying anger, disillusionment and discontent that’s manifested as a rise in populist politics and boneheaded nationalism across the world is driven by a deep-seated dissatisfaction with the status quo. There are a lot of people pissed off that the world has apparently enjoyed decades of economic growth and they still feel like they’re struggling to make ends meet.

The ’neo-liberal’ philosophy of minimising the role of government and instead allowing free enterprise to unleash the potential of unbridled market forces was adopted by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan as the solution to another period of economic dislocation. The problem is, once the path toward recovery was established it’s been followed all the way to the other extreme, and extremes are rarely a good place.

Some 30 years after neo-liberalism was seen as saving the developed world, labour’s share of the economic pie has shrunk to 60-year lows in Australia, 70-year lows in the UK and as low as it’s ever been in the US. This has contributed to inequality hitting levels that in the past underpinned social and economic upheaval, elevating it to the current buzz-topic across developed economies globally. However, effecting the change required to even things up again requires coming up with a way to undertake significant redistribution, which is almost always via the tax system, so it will either take brave and foresightful politicians, or some kind of popular revolt.

The start of neo-liberalism: a solution for the times

When Margaret Thatcher was voted in as the leader of Britain’s opposition Conservative Party in 1975, unemployment was super low at about 4% but the inflation rate peaked at an eye-watering 27%, and, after GDP growth had hit 7% in 1973, the country was in recession with growth at -2%. It was a time when unions regularly threw their weight around and paralysing strikes would hold the economy to ransom; the so-called ‘winter of discontent’ in 1978-79 saw almost 30 million working days lost to strikes, the most since 1926, which led to the May election where the Labour government suffered an almost record defeat.

People were demanding change and the new Thatcher government took power on a platform of confronting the unions and allowing markets to flourish by getting government out of the way. After a couple of bumpy years early on, characterised by sometimes violent conflicts over strikes, between 1982 to when her government was voted out in late 1990 GDP growth in the UK averaged 3.3% per annum, GDP per capita had more than doubled, the share market had more than tripled and inflation had fallen from 18% in 1980 to 9.5% in 1990.

Times were good and Thatcher’s neo-liberal philosophies were enthusiastically embraced across the Atlantic by President Reagan, with his now legendary assault on ‘big government’ and the unshackling of corporate and market power. In 1980, the year Reagan was elected, things were grim for the US: inflation was running at 13.5%, unemployment was 7.2% and rising and the economy was in recession. By the time Reagan left office in 1989, having pursued his ‘Reagonomics’ version of supply-side economics (which argues cutting taxes and reducing regulatory burdens leads to more growth and the benefits will ‘trickle down’ from the top all the way to the bottom), inflation was 4.6%, unemployment was 5.4% and GDP had averaged 4.4% per annum since 1983. The US stock market more than doubled during Reagan’s tenure and the go-go, get rich era of the ‘80s was captured by the inimitable words of Gordon Gekko: “greed is good”.

The concentration of money and power

With such a stunning turnaround in economic fortunes, why wouldn’t you continue on the same path? If a bit is good then more has to be better, right? Across the developed world, but especially in the Anglosphere, governments continued to reduce their role in markets by cutting back regulations and selling off publicly-owned assets and enterprises, allowing companies to go on to even bigger and better things.

In the US, hand in hand with the rollback of those pesky market regulations and the increasing concentration of wealth, the ultra-rich built an increasing political influence. In the landmark, and widely criticised, 2010 Citizens United ruling the Supreme Court paved the way for unlimited political donations through “PACs”, or Political Action Committees, not only by individuals but, almost incomprehensibly, by companies as well. According to The Harvard Magazine, so-called super-PACs accounted for 22% of total donations in the 2012 presidential race, but by 2016 it was 37%. What’s more, The Washington Post reported that only 50 donors accounted for almost half the funds raised. While there are a few very high profile left-leaning billionaires, like Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Michael Bloomberg, in a 2018 paper, academics from Columbia and Harvard concluded the vast majority of America’s top 100 billionaires quietly, but actively, support right-wing organisations. The most notorious of those are the Koch brothers, each worth an estimated $50 billion, and responsible for creating the super conservative Americans for Prosperity (AFP) group, which boasts some three million grass roots members and aggressively promotes a free market, small government agenda.

A key part of AFP’s activities has been campaigning for the emasculation of trade unions, which reaps a double harvest: it strengthens the corporate sector by dramatically improving the stability of labour markets, largely by preventing workers from being able to collectively bargain, plus it undermines one of the principal sources of funding for the Democrats and left-leaning causes. In 1983 more than 20% of US workers belonged to a union, and by 2016 it was less than 11%, and the number of private sector workers in a union had fallen to the lowest level since the Great Depression. This trend has been echoed in the UK, where by 2017 trade union membership had fallen to an all-time low and the 300,000 working days lost to strikes was amongst the lowest since records started in 1899. And in Australia union membership has fallen from 51% of all workers in 1976 to 14% today, the lowest in at least 70 years.

The Pew Research Centre writes that stripping workers of their collective bargaining power has resulted in widespread wage stagnation, with real wages for average workers in the US remaining virtually unchanged since 1979. For a stark illustration of the difference between the pre and post neo-liberal eras, between 1950-1980 real incomes for the bottom 20% of US wage-earners grew at an almost identical rate to the top 5%, but between 2000-2018, the top 10% saw five times the increase in real wages of the bottom 10%. Today in the US, the biggest companies can wield such extraordinary levels of power that 25% of workers are being subjected to non-compete clauses – even fast food workers! The Federal minimum wage has been set at US$7.25 since 1991 and we were reminded during the recent government shutdown that a 2017 survey found 78% of American workers live paycheque to paycheque, and last year a Fed survey found 40% of adult Americans would be unable to come up with US$400 in an emergency.

The story on wages reads quite similarly in Australia, where in the March quarter of 2017 labour’s share of national income fell to its lowest since 1960. Over the 12 months to the end of March 2017, Australian workers received less than 10 cents of each extra dollar in GDP that they produced, which was the slowest rate of flow through ever recorded.

The GFC – a step too far?

It’s possible a turning point came with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the epicentre of which lay in the American housing heartland. The finance industry, and most especially Wall Street bankers and the credit rating agencies, screwed up monumentally; outright greed, combined with negligence and fraud, culminated in a near death experience for the world’s financial system. The only way to save it was using the public purse – taxpayers’ money – to bail out the private banks, starting in the US, where the 2009 budget deficit blew out from an original forecast of US$407 billion to eventually hit US$1.4 trillion (these days the word trillion gets thrown around a fair bit and it’s easy to become a bit blasé about it, but to put that amount of money into its mind blowing perspective, one billion seconds is just short of 32 years, one trillion seconds is just short of 32,000 years).

And no sooner was the US economy off life support than Europe took its place with its ‘sovereign bond crisis’, thanks to a combination of either over-indebted governments that had gorged themselves on apparently cheap debt in vote-buying public spending campaigns, or governments that became over-indebted because they felt they couldn’t afford not to bail out private sector banks and property companies teetering on the edge of collapse.

Those people entrusted with the stewardship of entire countries had overseen a gargantuan mess and seemed to be making things up as they went. The result: economies all over the world were slammed into reverse, in 2009 US GDP growth fell to -2.8% and unemployment hit 10%, and EU growth was -5.4%, with unemployment eventually hitting 11% in 2013, while Spain and Greece both reached unemployment rates of 27%.

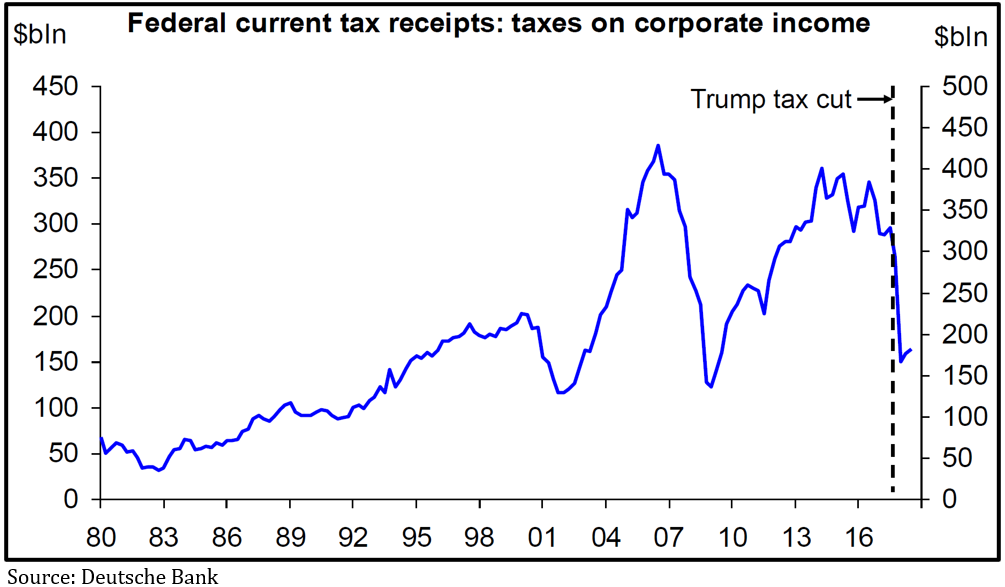

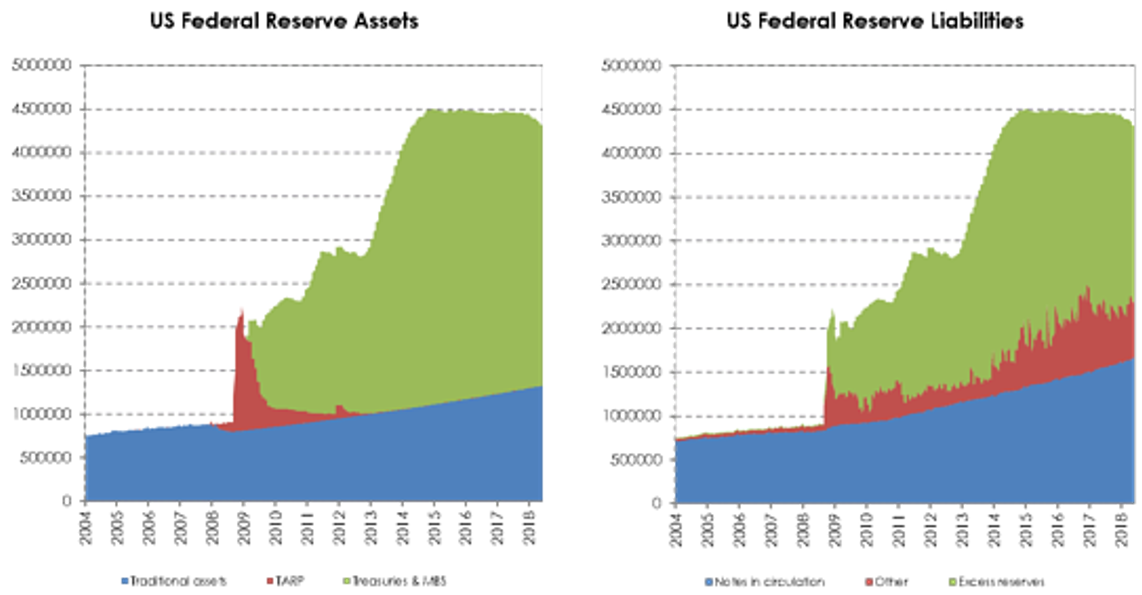

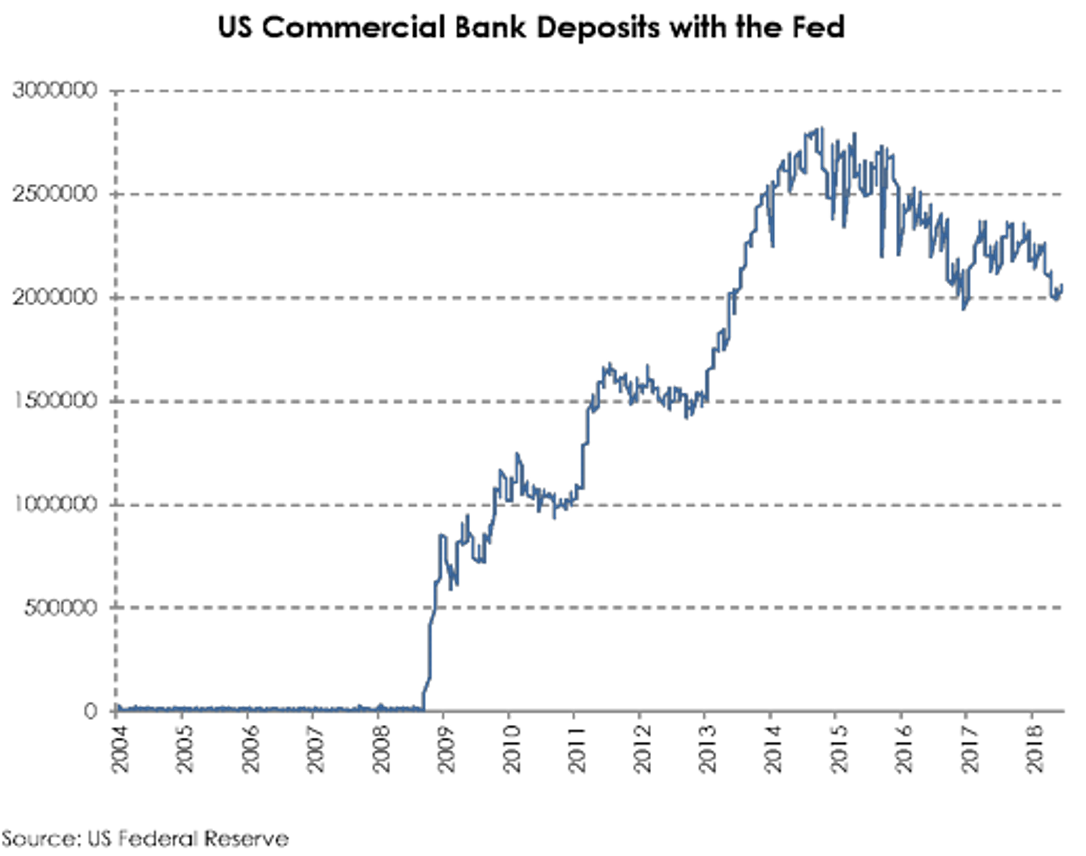

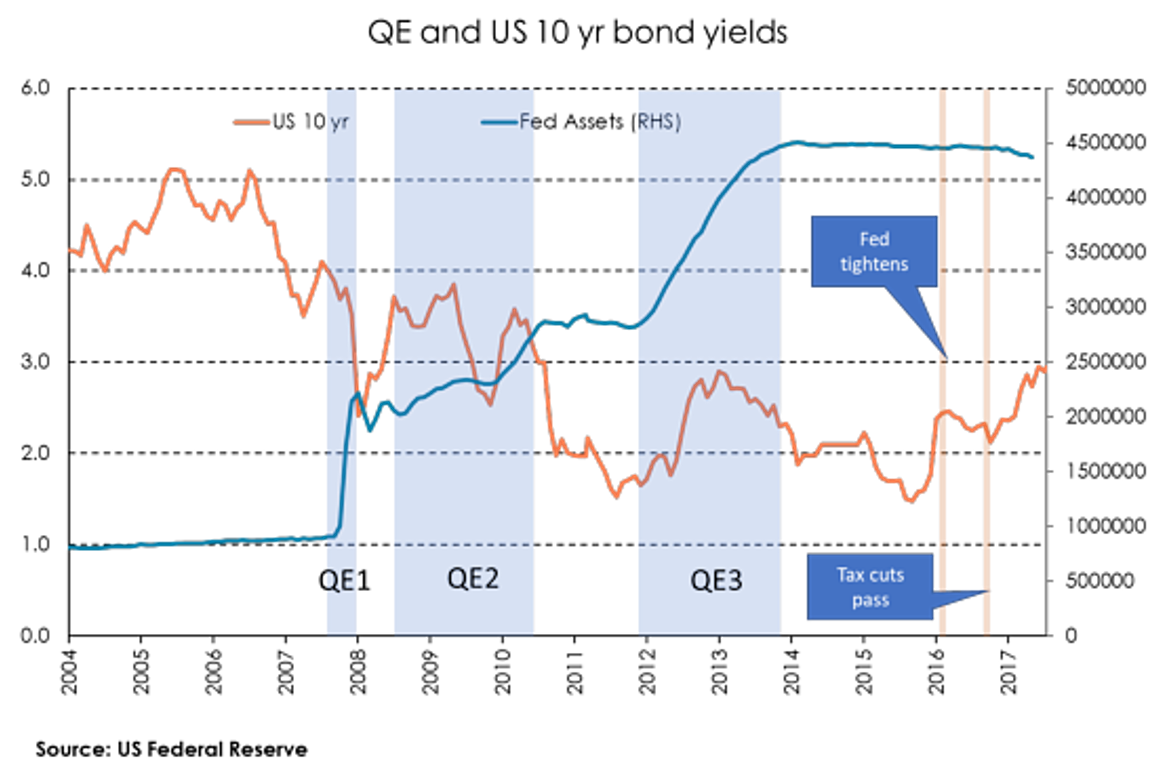

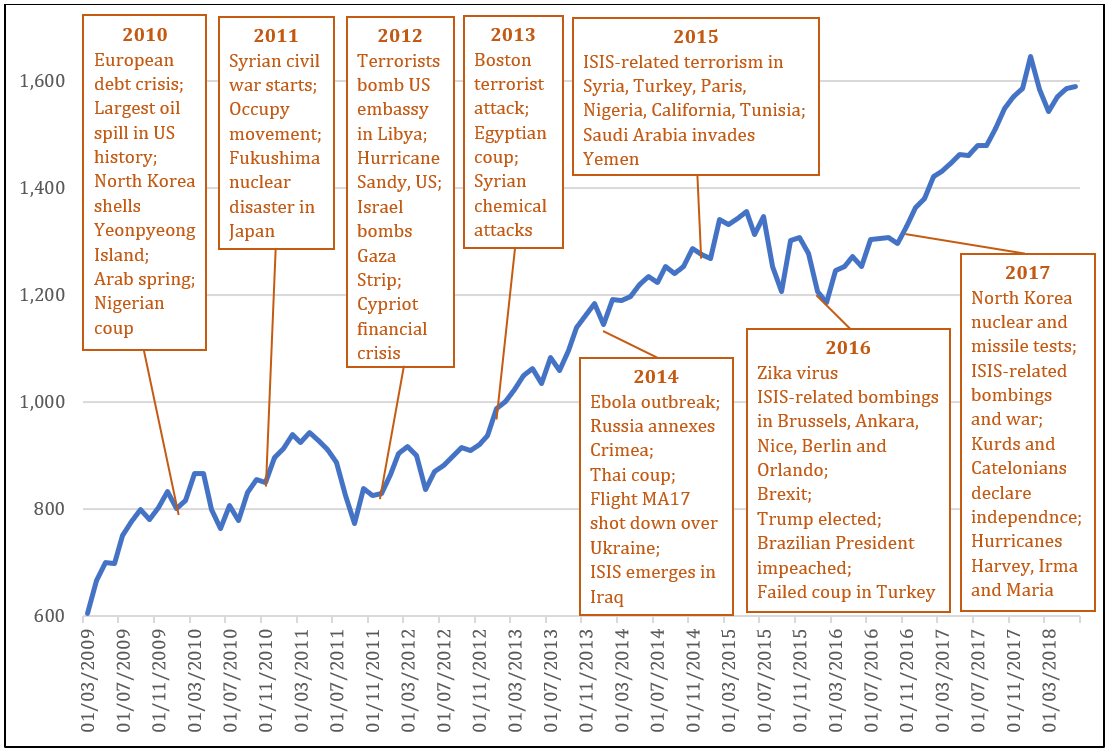

But despite plenty of evidence, and hundreds of candidates, nobody was found culpable for the greatest financial disaster in three generations. Although US banks were fined and had their lending wings clipped, Wall Street bonuses were back at record levels within a few years. What’s more, the remedy used to keep the markets from falling even further, where central banks from the US, Europe, Japan and the UK pumped unprecedented amounts of liquidity into the financial system, inflated the value of all kinds of assets, from shares, to property, to art collections, to fancy number plates – the kinds of things already wealthy people own.

Is it any wonder the average person was left feeling the system is rigged?

The growth, and growth, and growth of inequality

Inequality has become the topic du jour, but it’s worth revisiting some of the numbers. In the three decades after World War 2 the US enjoyed one of its strongest periods of economic growth as manufacturing took root and blossomed across the country. Households greedily consumed all the new-fangled appliances and most of them were “Made in the USA”, everything from washing machines, to televisions, to cars. An endless string of new factories provided well paid jobs for unqualified workers, and as the nation got richer, everybody benefited.

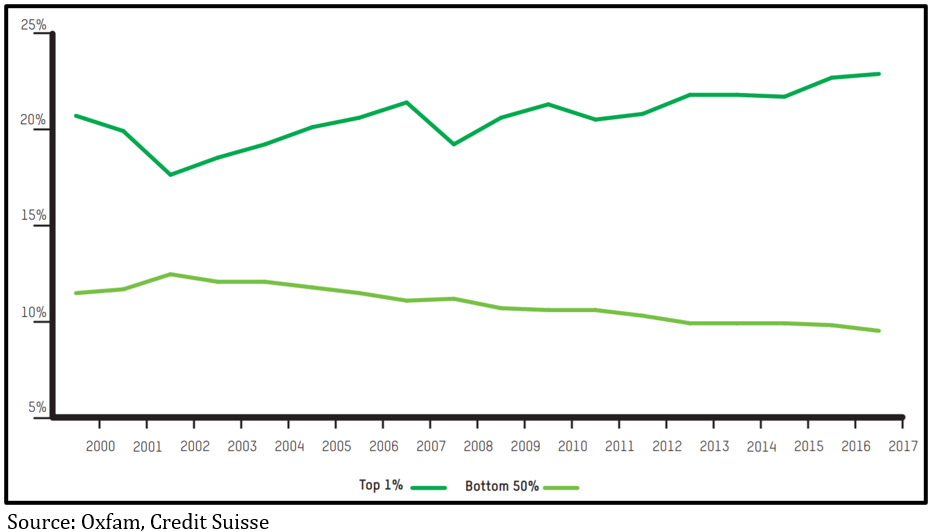

Then once neo-liberalism took hold things started to change. The US Congressional Budget Office found that between 1979-2011 the ‘market income’ for the bottom 80% of workers grew by 16%, or less than 0.5% per year; for the next 19% incomes grew three and a half times faster, at 56%, and for the top 1%, incomes grew almost 11 times faster, or 174%. In 1965, the average CEO earned 20 times the wage of the average worker, and by 2018 that number had exploded to 361 times for the CEO of an S&P500 company.

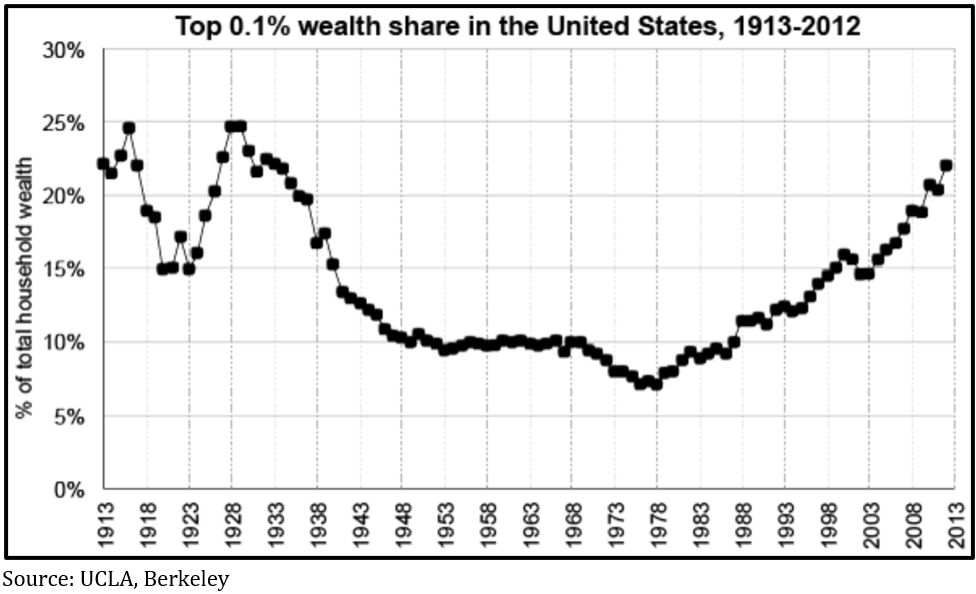

But that’s just income, the richest people also own lots of assets, often interests in companies, and the value of those assets has rocketed as well, especially since the GFC. In 1979 the top 1% in the US owned 24% of the total wealth and by 2012 that had increased to 42%, so not far off doubling. But what is far more telling, the share of wealth owned by the top 0.1% had sat around 10% for most of that glorious post-war period and bottomed out in (you guessed it!) 1979 at 7%, but then more than tripled to 22% by 2012! See chart 1.

Chart 1: The Top 0.1% wealth share in the United States, 1913-2012