The December stock market correction was a timely reminder to get you thinking about whether your portfolio has enough built in safety features. But just like a car crash, it’s safer and smarter to worry about those features before you find out you really need them.

How much risk you’re prepared to take on in your portfolio is the single most important decision you’ll make. If you take on too much you’ll be lying awake at night worrying about when a market correction’s going to stop and battling the temptation to dump your shares and hide in cash, but if you don’t take on enough risk your portfolio could struggle to support the lifestyle you want.

The ‘risk’ in a portfolio largely comes from its exposure to growth-oriented investments, like shares and property, while the ‘air bags’ come from defensive assets, like bonds, cash and, sometimes, so-called ‘alternative investments’.

Obviously, a portfolio that’s split equally between growth and defensive assets is going to be far less volatile, but over the long-run will be expected to have lower returns, than one that’s 90 per cent growth and 10 per cent defensive.

Even defensive assets have their risks

Cash is pretty much the best air bag available for a portfolio: it has zero volatility; perfect liquidity, meaning you can access it whenever you like and in whatever amount you want; bank accounts up to $250,000 are government guaranteed, and it also has what you might call ‘option value’, in that it enables you to take advantage of opportunities if they arise.

The price you pay for that security is a low return, in fact, money held in an ordinary bank account is usually going backwards after accounting for inflation. Even the average return on a three-month term deposit after accounting for inflation has been only 0.4 per cent per annum over the past 5 years, and less if you’re paying tax on it.

Bonds are the next best defensive asset, but you need to be careful about what type of bonds they are: government or corporate.

Corporate bonds are issued by a company as a way to fund itself instead of going to a bank. Obviously there are big, safe companies that are far less likely to default on their debt obligations and they get a higher credit rating, like A-grade, and there are those that are not so safe and reliable that can get rated as ‘junk bonds’ or ‘high yield’, which is anything below a BBB rating.

It makes sense that the market’s view on a corporate bond will change in line with how that company’s performing. If a company’s struggling investors will demand a higher yield to compensate for the rising risk of default, which means the price of the bond goes down, so it’s entirely conceivable you can lose money on that company’s bond.

The problem is that same struggling company’s shares will probably also be going down at the same time. That means corporate bonds are often ‘positively correlated’ to equities, meaning they go up and down at the same time, which is the opposite of what you want from a defensive asset. Not surprisingly, corporate bonds are normally categorized as a growth, or semi-growth asset – no airbag there.

Government bonds will also have a credit rating, so if you buy the bonds of a steady, developed nation like Australia or the US, the chances of them defaulting are almost nil. Again though, the price you pay for lower risk is a lower return. But think of it like this: if you were told airbag A reduces the risk of injury by 50% and costs $500, whereas airbag B reduces the risk by 90% and costs $1,000, what would you do?

There are a few tricky parts to government bonds: first, to get exposure you’re going to have to use a fund of some sort, either an ETF which just follows an index, or a managed fund that tries to earn a bit extra; second, ‘real’ returns after inflation can be surprisingly low again – over the past five years Australian 10 year bonds have averaged a smidge over 1% – but remember their job is to be defensive; finally, and importantly, over time the correlation of bonds and shares can change.

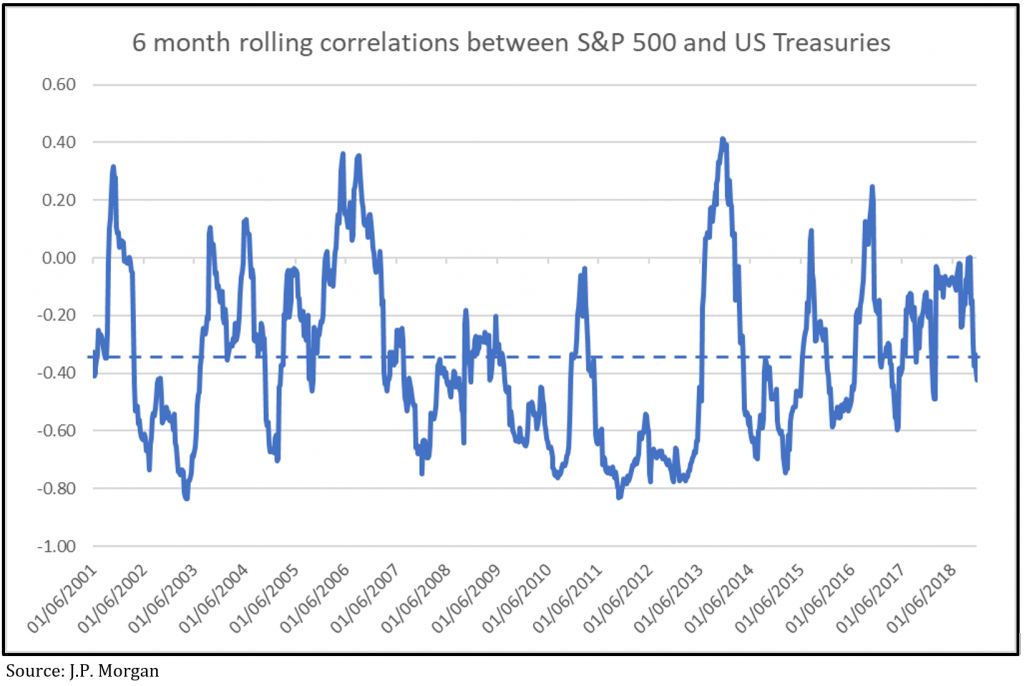

Typically investors presume government bonds are going to zig when equities zag, meaning they are ‘negatively correlated’. A great example was in 2008 when Australian shares fell 38%, while Australian bonds rose 15% and international bonds went up by 9%. But the chart below shows that since 2001, while the average of the rolling six-month correlation between US shares and bonds was -0.35, it never stood still and covered a broad range, from -0.8 to 0.4. In other words, while government bonds tend to perform well during a share market correction, there’s no guarantee.

How did bonds go over the course of the recent correction? US shares fell 20 per cent from their peak on 20 September to the December low, while the iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF rose 0.5 per cent over the same time.

Here in Australia the Accumulation Index (which includes dividends) fell 13 per cent from its August peak to the late December low, while the iShares Core Composite Bond ETF, which is about 90% government bonds, went up by 1.0 per cent.

As usual in investing, there is no perfect solution to finding an airbag for your portfolio, but the right exposure to the tried and true defensive assets of cash and government bonds should at least help stop you losing sleep worrying about the next crash.