The big spending that could keep the US out of recession

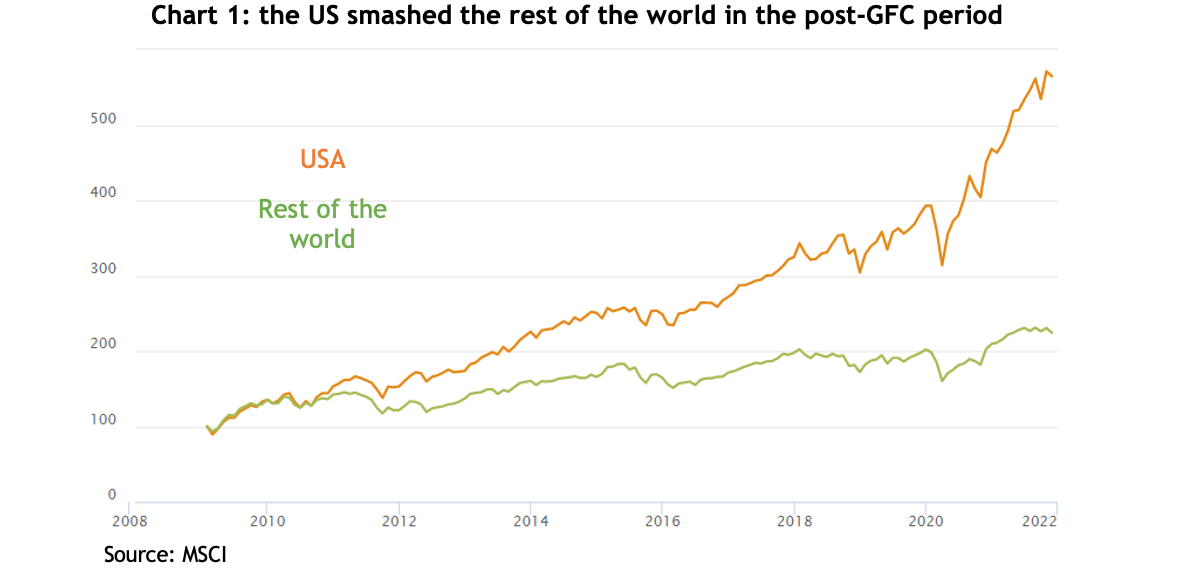

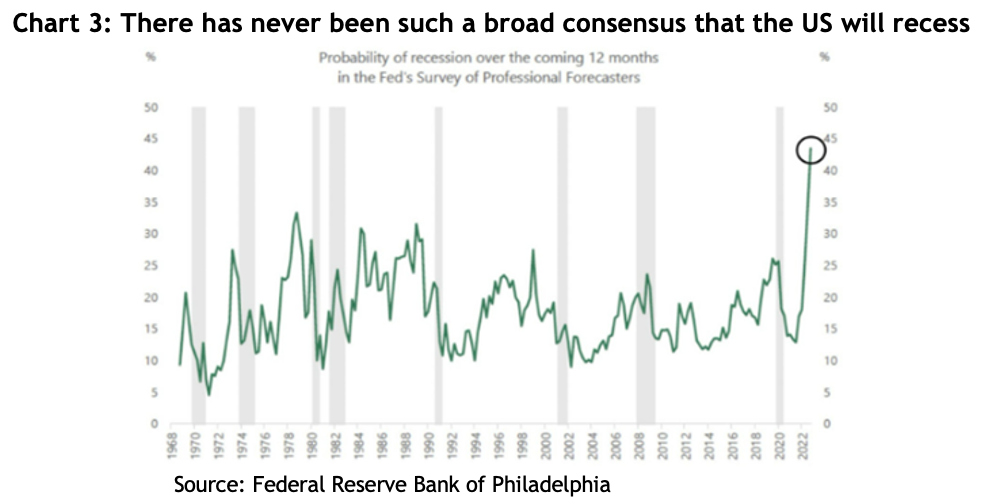

In September last year, Bloomberg reported that 100 per cent of surveyed economists expected the US economy to recess in early 2023, and strategists were warning of calamitous markets ahead. Of course, that didn’t happen, and whilst GDP growth of a smidge above 2 per cent per year isn’t going to knock anybody’s socks off, it’s far from going backwards, and the US share market rose 20 per cent to the middle of 2023.

Economists tend to follow an approach where they try to fit today’s circumstances into a historical analogy, saying “I think what’s happening with inflation and interest rate rates today is not dissimilar to the 1970s/1980s/whatever period”, and base their forecasts on what transpired back then.

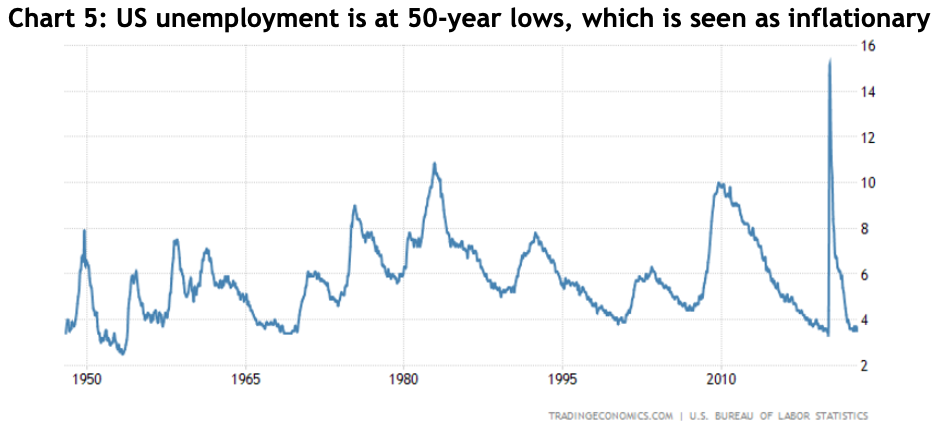

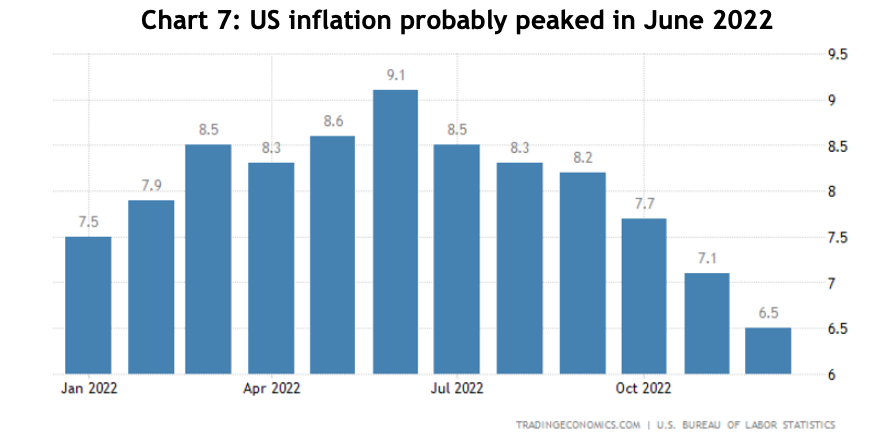

The thing is, none of those past rising interest rate episodes were preceded by the federal government shoving 25 per cent of GDP into household bank accounts, which was what happened with the COVID stimulus cheques. That massive fiscal injection had two effects: first, it set the economy on fire, sending unemployment levels to 50-year lows; and second, households had never enjoyed such a large savings buffer to cushion against rising prices. As a result, the US economy’s resilience took orthodox economists and strategists by surprise.

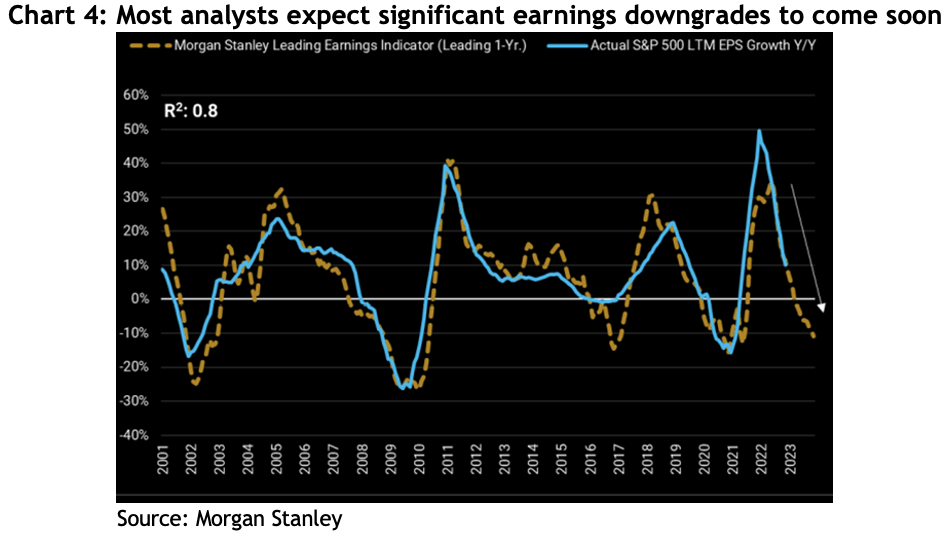

Once again, we are seeing a growing consensus that the US economy is going to recess next year, which brings with it the usual talk of America sneezing and the rest of the world wrestling with swine flu.

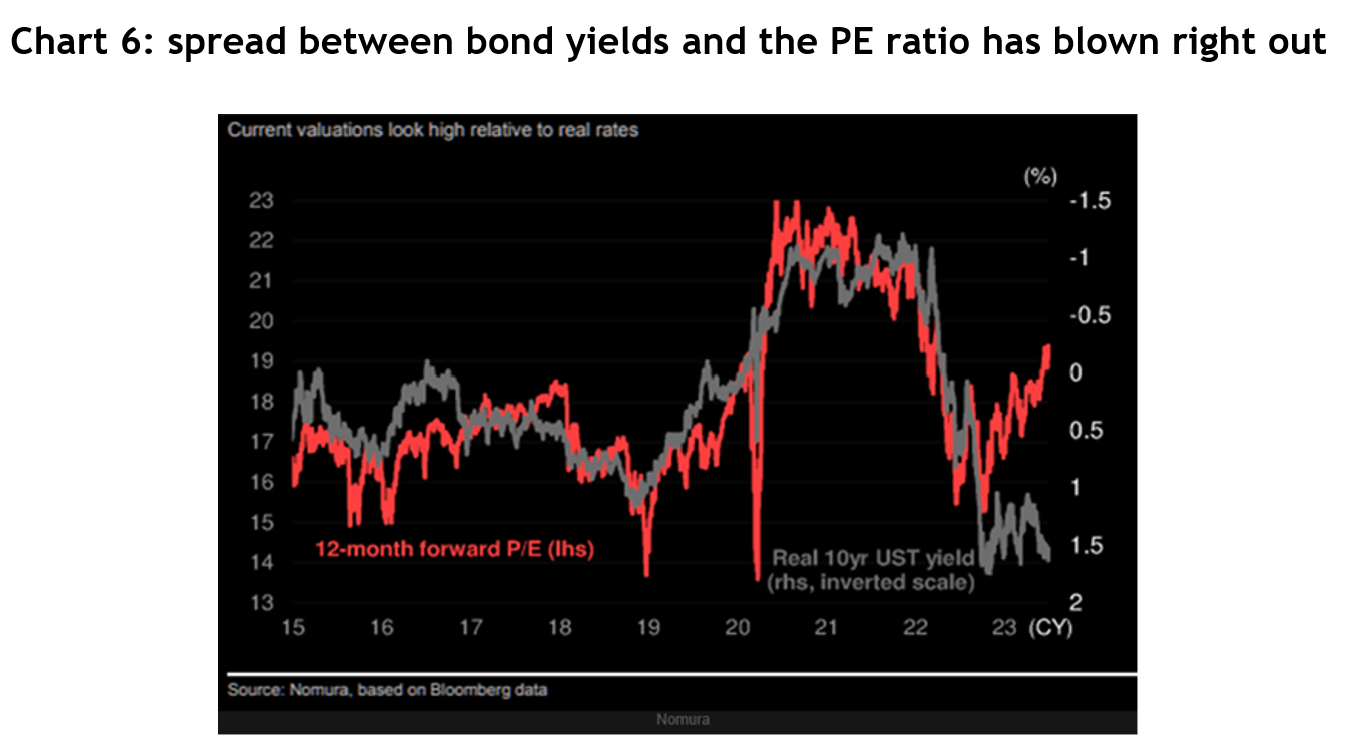

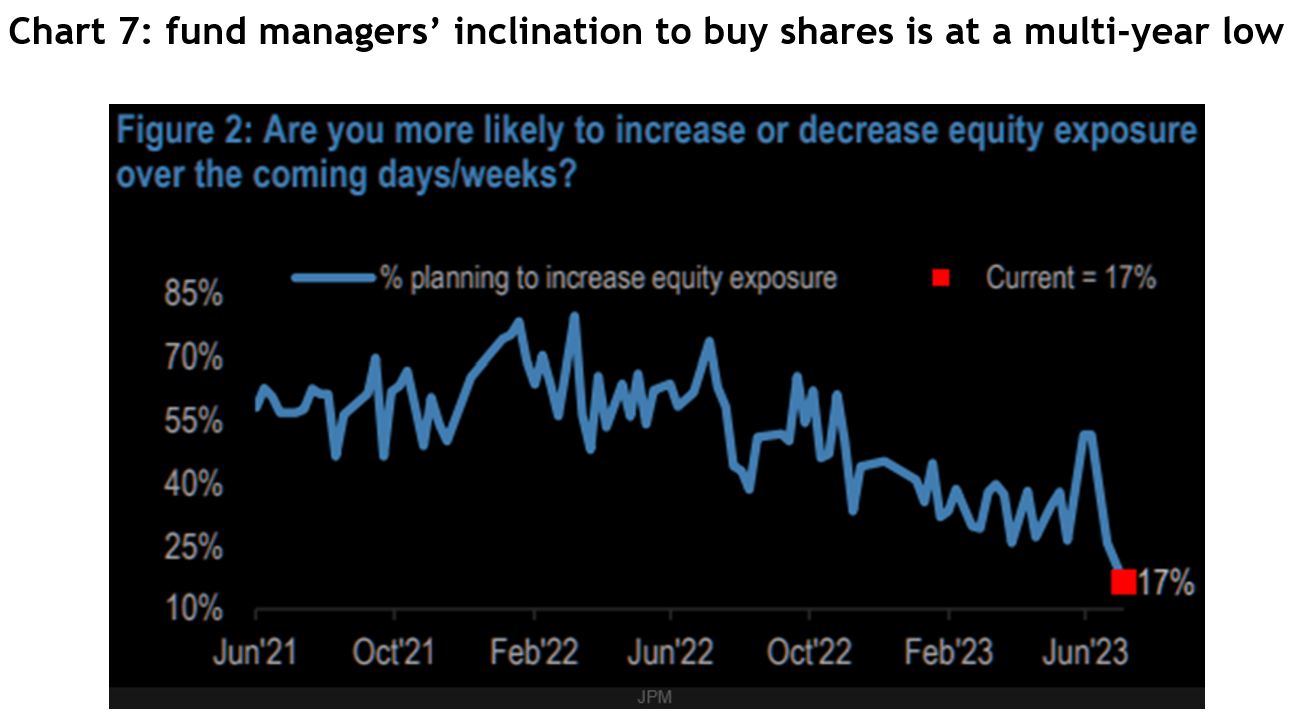

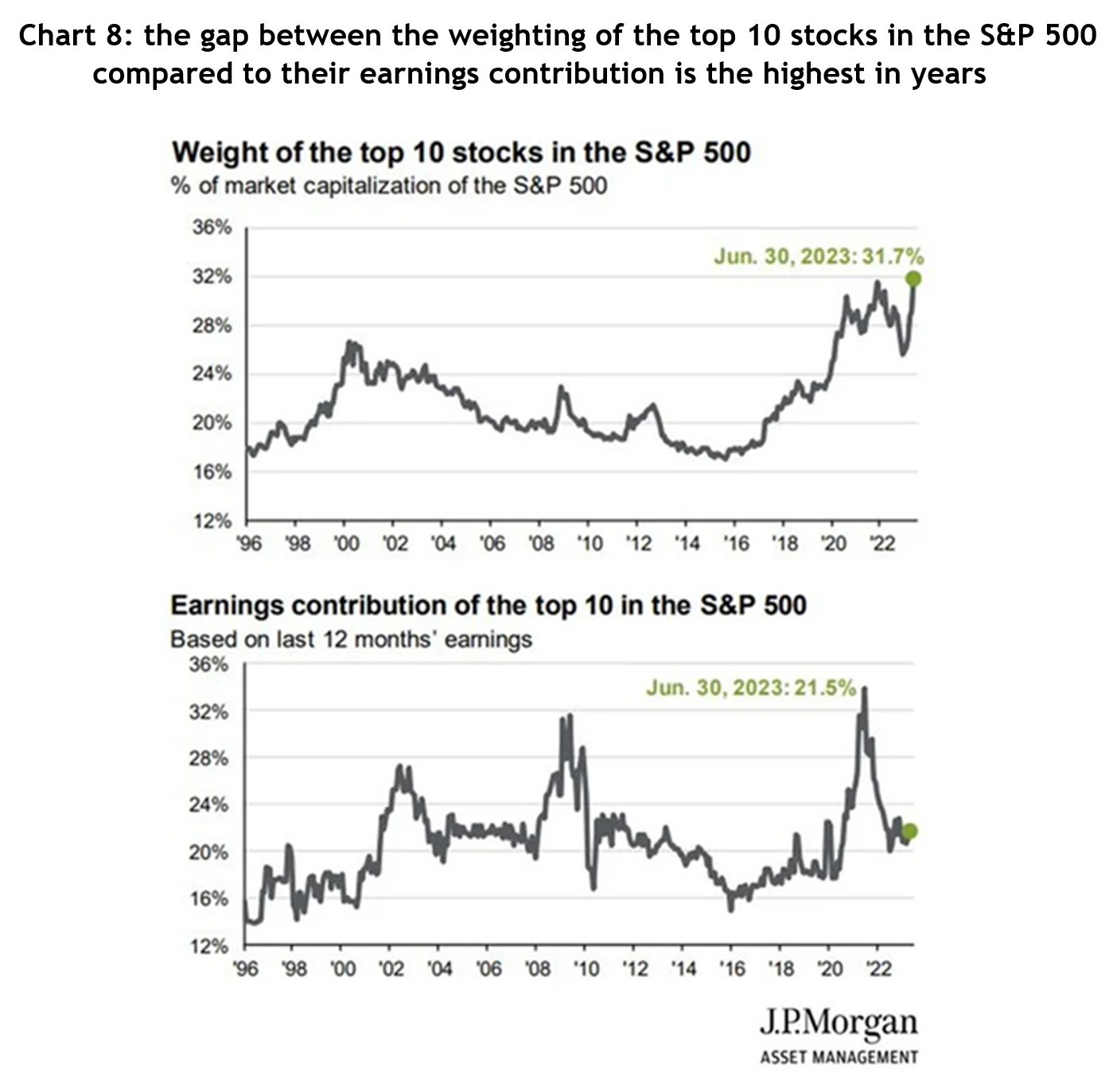

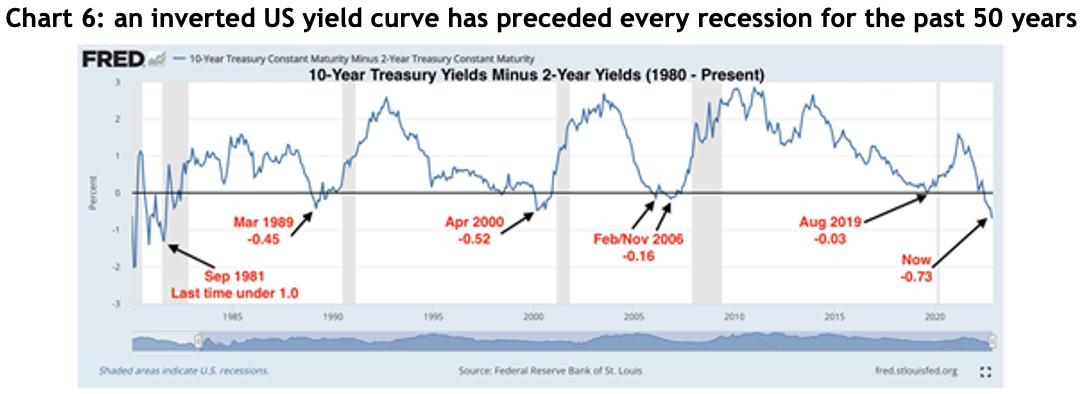

Concerns that the Federal Reserve is going to increase interest rates again, that rising bond yields will make shares increasingly less attractive, that the now long-standing inverted yield curve will somehow work its voodoo, that consumer confidence is falling, and households are running out of those excess savings, combine to paint a grim picture. Throw on top of all that a dysfunctional US congress and an approaching election plus the ongoing problems China is experiencing and it’s clear why the bears are once again on the prowl.

However, if you look hard enough, just like last year, there are some signs pointing in the other direction; signs that tend not to feature in most forecasts. And, again just like last year, they revolve around some significant fiscal injections and consumers that might be in a better spot than economists give them credit for.

The first of those fiscal injections is the interest the US government is paying on the more than USD33 trillion of bonds that are on issue, which has risen over the past three years from USD500 billion per year to more than USD900 billion. That may not be going into the pockets of the people who would spend it all, but it’s still going into the economy.

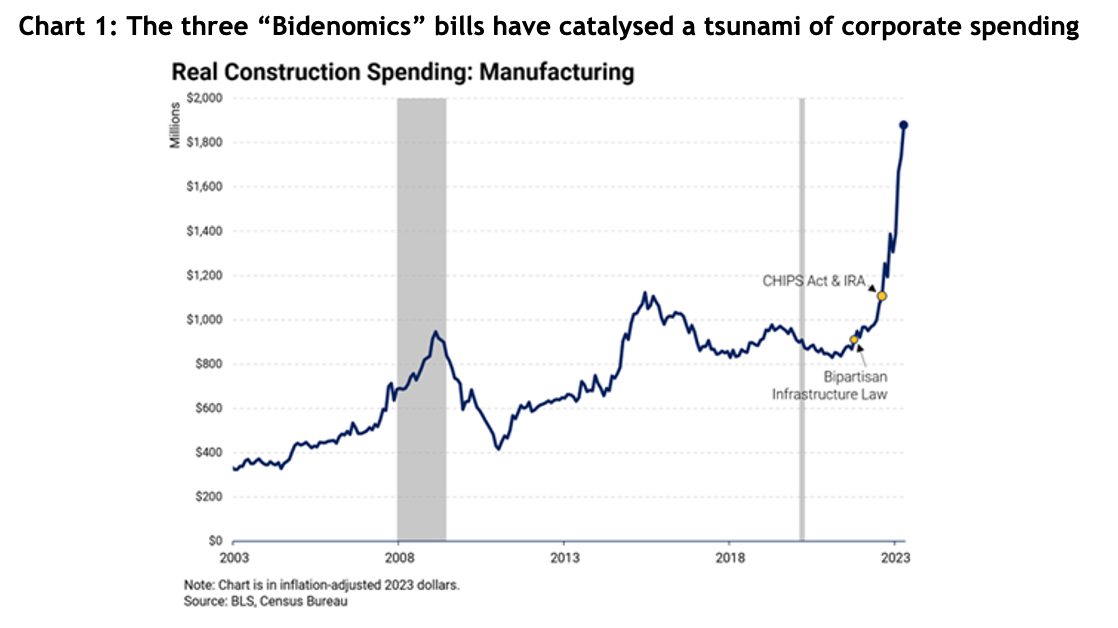

The second is the three signature pieces of legislation that have been dubbed ‘Bidenomics’, the CHIPS Act, the Infrastructure Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which between them earmark more than USD2.25 trillion of government spending.

Between them, that amounts to more than 12 per cent of the US economy being injected through government spending programs, which are on top of the usual budget items. What’s more, the IRA, which basically invites any company with a decarbonisation project to apply for tax deductions, rebates or subsidies, is open ended, and Goldman Sachs estimates the amount being spent has increased from the original projection of USD780 billion to more like USD1.2 trillion.

When you add them up, it’s a ton of money being thrown into the economy, and those three government policies have catalysed a tsunami of corporate spending, with data from the US Treasury showing real manufacturing construction spending doubling to USD1.9 trillion over the year since they were passed – see the chart below – and non-residential construction spending in general is up 15% since the infrastructure bill. Overall, private sector spending has gone up three times more than public spending. In other words, the government’s policies are crowding in private sector spending.

Regrettably, Australia is in the opposite position, with the federal government boasting of a surplus, which is sucking money out of the economy at a time when households spending is coming under a lot of pressure.

As for US consumers, while it’s true they’ve almost run out of excess savings from COVID, there’s still a base level of savings, plus household bank deposits are more than four-fold higher than pre-COVID at USD4 trillion. Then there’s the 50 per cent rise in money market fund balances to around USD6 trillion and a similar rise in home equity to almost USD32 trillion.

In other words, American consumers have a lot left in the tank to maintain that legendary appetite for spending.

It’s still entirely possible the US economy will hit a recession-sized bump in the road, but it’s far from a certainty. Smart investors will know better than to put their faith in economists and strategists who get things wrong as much as they get them right.