2022 – the scorecard

By some measures, 2022 was one of the worst years for financial markets in the last century and it was all due to central banks aggressively tackling a sharp rise in inflation.

Global bond markets suffered their worst year ever, with the Bloomberg Bond Index falling 13%, compared to the previous worst fall of only 3%.

Share markets were very mixed, with previous laggards like Australia and the UK doing relatively well (though still falling), while the US, which had left the rest of the world in its dust over the past 13 years, recording its seventh worst year in the past 100 – see chart 1.

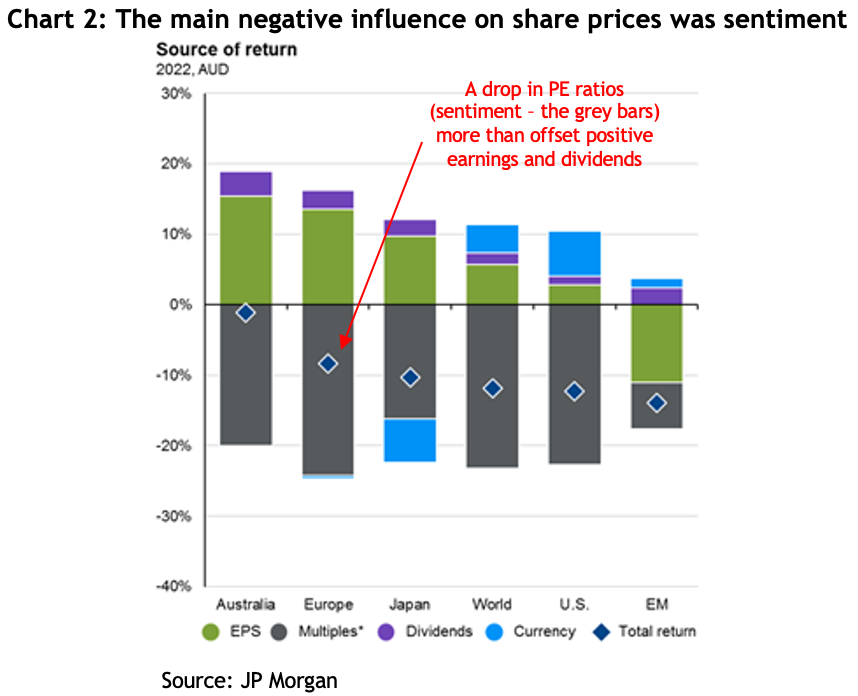

The big falls on global share markets was by and large because of ‘PE compression’, meaning the price to earnings ratio at which investors were prepared to buy stocks fell. That reflects a change in sentiment, as opposed to a fall in earnings (the opposite to what happened in the GFC). The grey bars in chart 2 show the extent to which that change in sentiment offset any positive contribution from earnings growth and dividends (the chart is in AUD which is why there’s a currency effect as well).

The huge difference in returns was due to the resurgence of ‘value’ stocks, the old fashioned sectors like resources and industrials, smashing the ‘growth’ stocks, like tech.

Lessons from 2022

Financial markets throw up new lessons all the time, here are a few of the takeaways from last year.

Be wary of central banks: as late as November 2021 the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Philip Lowe, reiterated the board’s often repeated view that inflationary pressures were not a concern to them and interest rates in Australia would not rise before 2024, six months later they began the most aggressive rate rise campaign in decades, with eight consecutive monthly rate increases taking the cash rate from 0.1% to 3.1%, with the likelihood of more to come.

The US Federal Reserve was the same and was more or less bullied by financial markets into launching aggressive interest rate rises, with seven consecutive increases taking their cash rate from 0.25% to 4.5%.

Don’t trust forecasters: out of a survey of 16 US forecasters, the lowest estimate for how the S&P 500 would go over 2022 was a 3.5% fall, the highest was an 11.1% gain, with the average being a 3% increase. The final result was a fall of 19.4%.

This just shows how tough it is to make forecasts. It’s a truism that over the long-term share prices follow earnings growth + dividends, which, according to chart 2, was about +3%. So it’s pretty understandable the average estimate came in at that level, but any strategist will tell you they hate making one year forecasts because sentiment is invariably the swing factor, and that’s simply impossible to guess.

Bonds can lose money too: over the past 40 years, when interest rates were on a long-term downward trend, bonds provided a counter-correlated air bag against falls in share markets, but 2022 was dramatically different. Government bond yields fell to all time lows in 2021, which increased their sensitivity to a rise in inflation. And while corporate bonds offered a better yield, they were also susceptible to repricing on concerns that companies would be more likely to default in a rising rate environment.

Base decisions on what you think will happen, not on what you think should happen: there were plenty of strong arguments that rate increases, which are designed to reduce demand by increasing the price of credit, were not the right weapon to use against inflation that was driven mostly by a combination of supply bottlenecks and companies opportunistically increasing prices.

If interest rates hadn’t risen as much as they did, it’s unlikely share markets would have fallen as much as they did. But the fact is central banks made it clear they were going to hike rates, and that was especially going to affect the growth stocks.

The falling tide can affect almost all boats: when markets go into a broad reversal because of a PE derating, it doesn’t matter if you avoid the clearly overvalued parts of the market, like unprofitable tech stocks, because even ‘fairly’ valued sectors supported by solid earnings can get whacked too, as we saw with highly profitable tech companies like Apple and Microsoft.

The bulls vs the bears

There is, as always, a raging debate between the bulls and the bears as to what 2023 holds in store. While it’s always prudent to bear in mind what Yogi Berra apparently said that it’s always risky to make predictions, especially about the future, here are some observations.

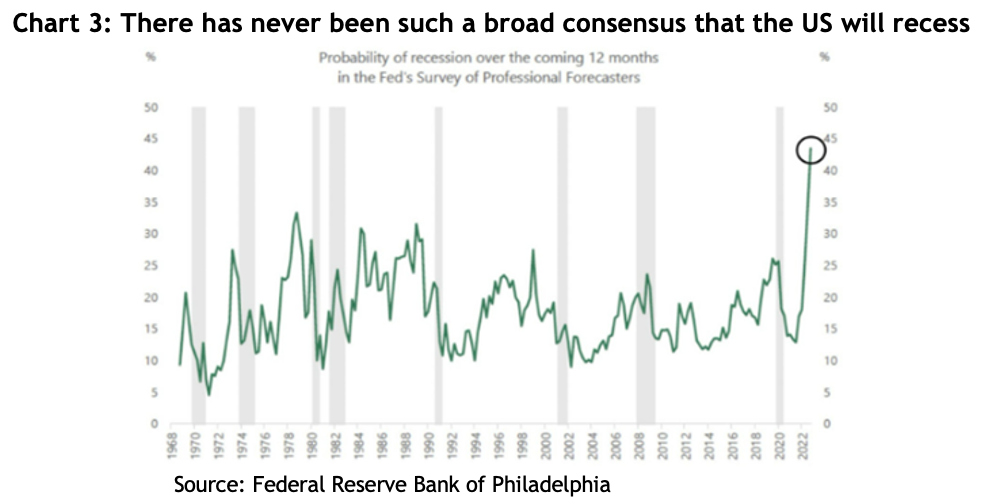

What the bears argue: the consensus view among investment banks and fund managers, especially in the US, is that the US economy will go into recession some time in 2023 – see chart 3, but that is not yet reflected in earnings forecasts.

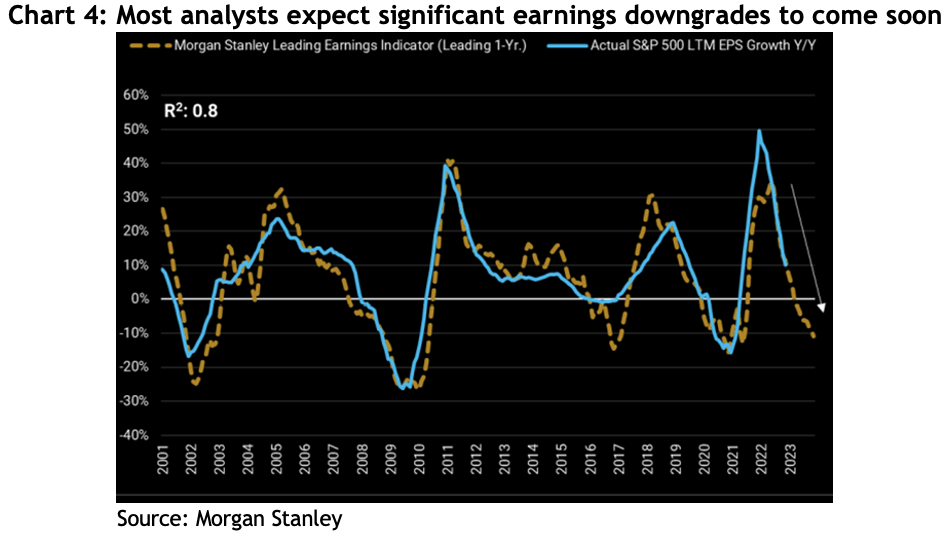

After recent downgrades, the consensus forecast for US earnings in 2023 is roughly flat, whereas in past recessions earnings have typically fallen 15-20% – see chart 4. As we pointed out above, markets normally follow earnings, so the consensus forecast for the S&P 500 this year is a 20-25% drop to new lows (between 3000-3300), before a recovery toward the latter part of the year (consensus is 4038 by year end).

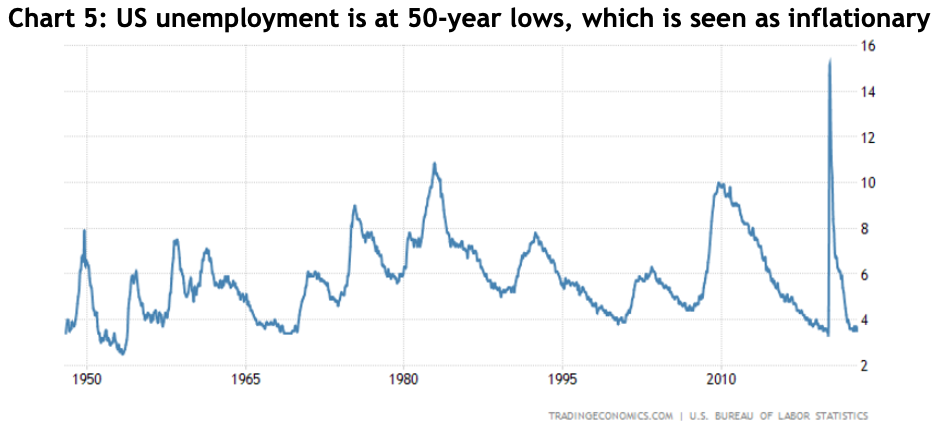

The expectation of a recession is based largely on the fact that there has never been an inflationary episode like we’re in now that hasn’t required the Fed raising rates so much that it drives the economy into recession. That view is reinforced by the US reporting its lowest unemployment rate in 50 years, which is generally seen as a harbinger of wage-driven inflation: orthodox economic theory argues there’s an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, and the Fed governors have repeatedly made it clear they are prepared to sacrifice jobs to reduce inflation, i.e. they will keep raising interest rates to choke the economy.

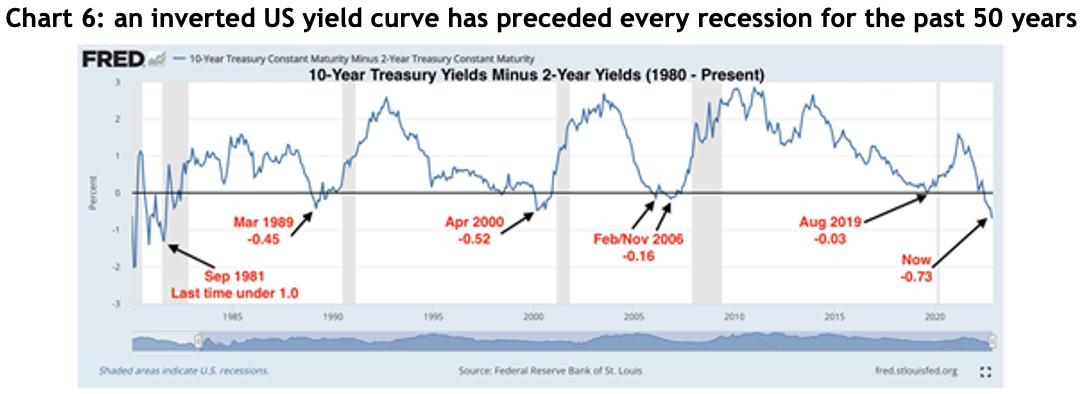

Finally, the bears point to the ‘inverted US yield curve’, meaning the yield on 2-year government bonds is higher than the yield on 10-year bonds – see chart 6. Every US recession for the past 50 years has been preceded by an inverted yield curve.

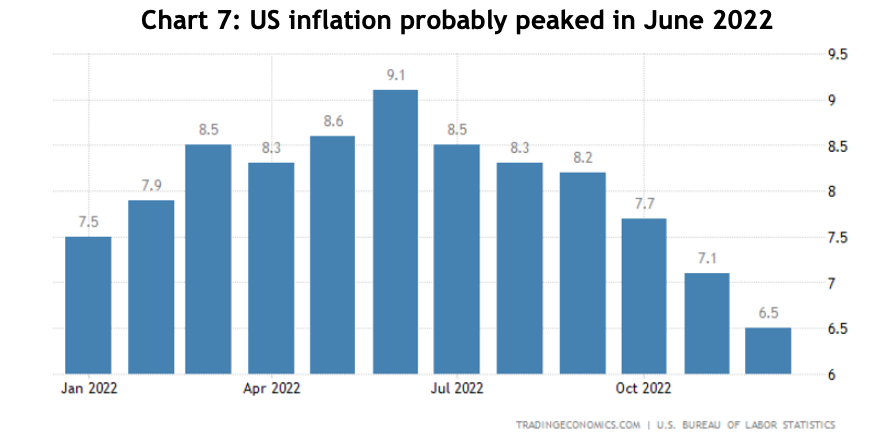

What the bulls argue: it looks for all the world like US inflation peaked in June last year, and it’s now declined for six consecutive months – see chart 7.

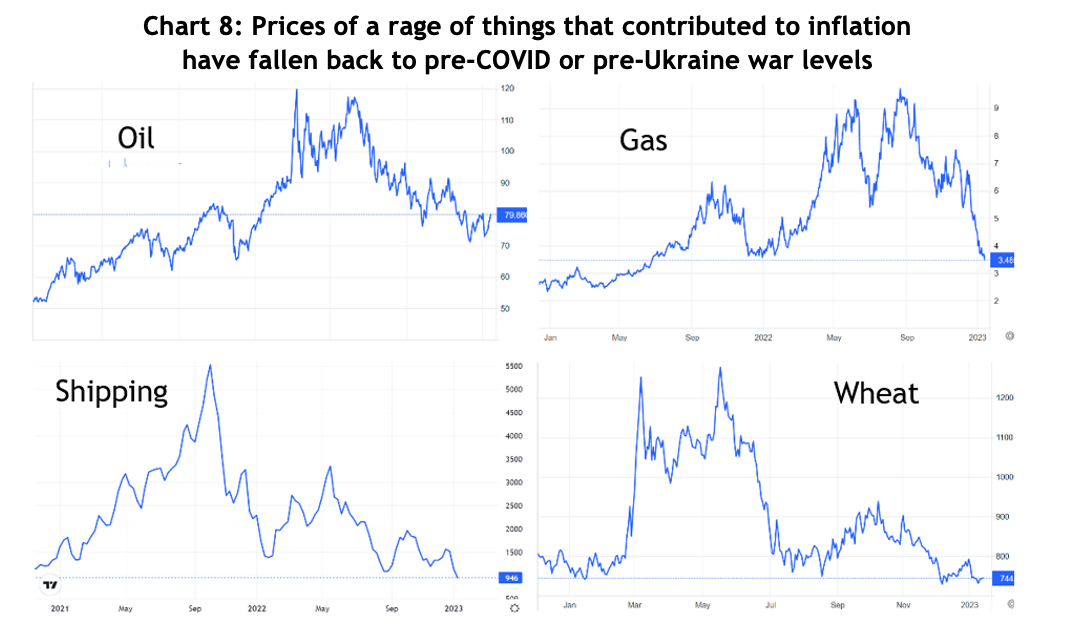

A range of things that caused prices to spike last year have fallen dramatically: freight costs are back to pre-COVID levels, oil and gas prices are back to pre-Ukraine war levels, as is wheat, semiconductor supplies have all but normalised, lumber is below where it was in 2020, etc. – see chart 8.

A quirk of how the US reports its inflation rate is that it compares the most recent month to what happened 12 months before. However, former Fed vice-chair Alan Blinder commented last week that if you instead annualise December’s monthly CPI number, which was -0.1%, the US is now experiencing disinflation!

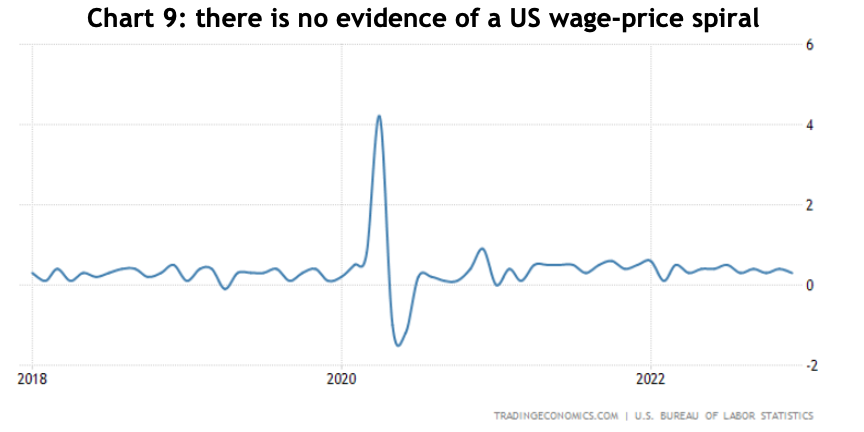

Also, the December US jobs report was full of good news: although the US economy added 223,000 jobs over the month, average hourly earnings growth was only 3.4% for the year, so lower than the inflation rate and slowing – see chart 9. There is absolutely no evidence of the wage-price spiral the Fed is so concerned about. These are all arguments militating against the Fed continuing to raise interest rates.

What about the risk of recession? US research group, Renaissance Macro, commented that “recessions don’t happen when real incomes net of government transfers (pension payments and the like) are on the rise and this is up 3.2% annualised since June.” In other words, households are doing OK, which should underwrite consumer spending.

Also, last year the US economy added 4.3 million jobs and Carson Investment Group pointed out that of the 17 previous years where the US added more than 3 million jobs, only once did the following year go into a recession, 1972.

What about the scary inverted yield curve? Last week, Professor Campbell Harvey, the economist who came up with the indicator, said he believes this time it’s a false signal.

What about the record that inflation has never fallen without the Fed pushing the economy into a recession? Two things: first, this inflationary cycle is different to previous ones insofar as it’s easier to identify the causes, like people being locked in quarantine only able to spend on goods and consequent supply chain bottlenecks, all of which are turning, or have turned, around, and second, there has never been a time when a rising interest rate cycle was preceded by a government injecting 25% of GDP directly into households. Even the lowest quartile of households are still sitting on net savings.

What about the prospects of earnings downgrades? Again, the ginormous amount of money from those fiscal injections is still bouncing around economies, which will help underwrite corporate earnings for a while yet. Also, historically the S&P 500 has bottomed out on average 6-9 months before corporate earnings – see chart 10. Another way of looking at that is the share market is a forward looking indicator and has a knack for factoring in all the news that’s out there well ahead of economists and analysts. The S&P 500 fell 27.5% at its worst, and it’s now down 17%, meaning it may well have already factored in all the nasty prospects of earnings downgrades.

Other economies and markets: I’ve focused on the US because that’s where all the best information and data is available. However, for Australia, the monthly inflation rate is still above 7% and hasn’t shown signs of slowing anywhere near as clearly as the US, partly because of the effects of floods on food prices, the reintroduction of the petrol excise and the high cost of housing. It’s considered a certainty the RBA will raise interest rates for the ninth time in a row when they next meet in early February, but Governor Lowe has indicated the board is prepared to be less aggressive and wait to see if their handiwork has had an effect. It’s difficult to find an Australian economist forecasting a recession.

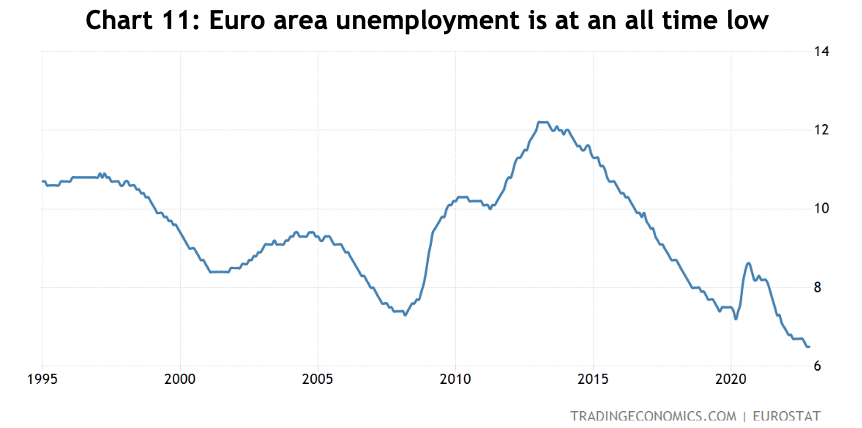

Europe was considered a basket case, but even there, a surprisingly mild winter has meant the nightmare scenario of energy shortages appears very unlikely and inflation also looks like it peaked in October and has fallen since. The natural gas price has fallen more than 60% from its peak in August and is now trading below where it was before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Unemployment in the Euro area is at its lowest since its inception and, although 6.5% is still significantly higher than the US or Australia, it is trending downwards – see chart 11. There are some brave souls arguing even Europe won’t go into recession.

Thoughts on where to invest

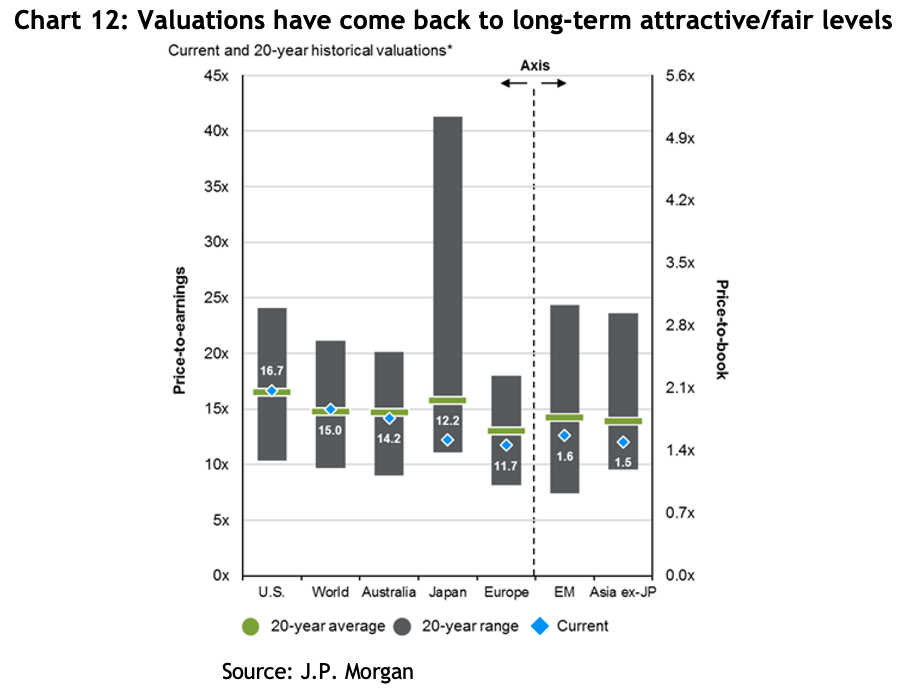

A benefit of the global selloff is that valuations have come back to relatively attractive levels. They might not be as bargain basementish as after the GFC, but they’re a lot better than late 2021 – see chart 12, especially for Japan, Europe and the emerging markets.

Not surprisingly given the Australian share market didn’t fall as much as others, it’s only just below the long-term average PE ratio and the US is a smidge above.

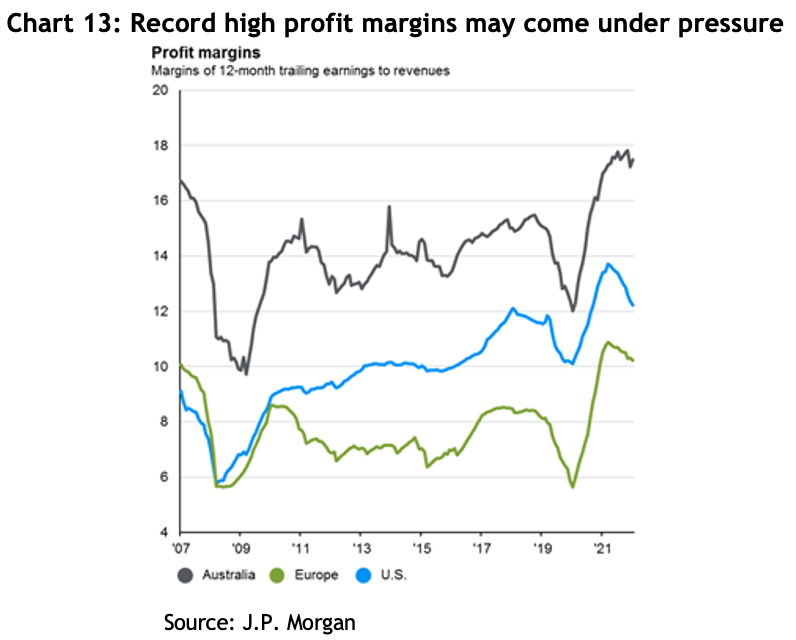

Record high margins: one issue is the record high level of margins in both the US and Australia – see chart 13. For the US that has largely come from the tech sector, not so sure about Australia, although it’s noteworthy that Australian margins have been higher the whole time. In 2021, of the 70% earnings growth reported by US companies, 50% came from margin expansion. It would not be surprising to see margins come under pressure.

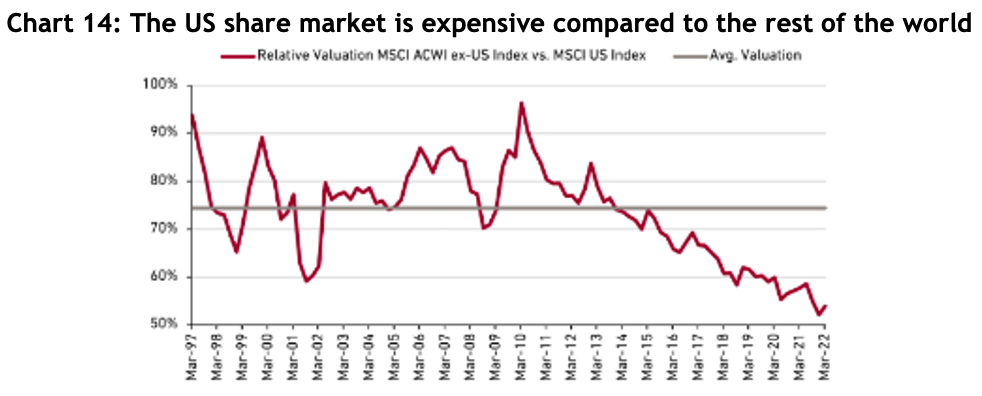

Outperformance of the US: since the GFC, US shares returned 14.1% p.a., which was 38% higher than Australian shares and 33% more than international. Chart 14 shows the extent to which the US has become expensive compared to the rest of the world, based on a combination of PE, price to book value and price to cash flow (the chart is only to March 2022 but it’s unlikely to have changed significantly since then). The point here is this chart has historically reverted to the mean, will it do so again?

As always there are great arguments on both sides as to why the US should or shouldn’t continue to do well versus the rest of the world. It remains a source of corporate and financial innovation with the lion’s share of globally recognised brands. However, it is expensive compared to the rest of the world, and the Republican dominated congress looks like it will be held to ransom by a handful of extreme views that could well wreak havoc with the government’s finances.

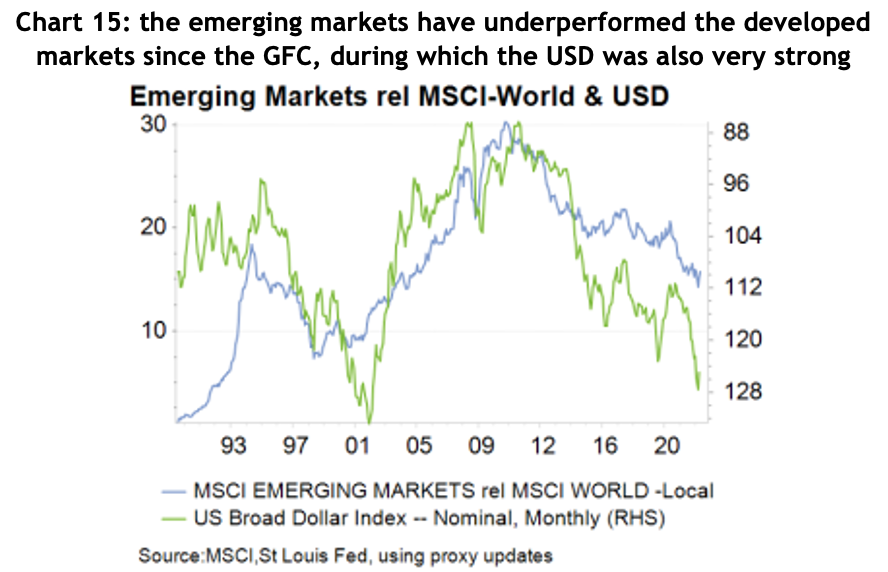

Will the emerging markets return to favour? Chart 15 shows the emerging markets smashed the developed markets over the 10 years up to the GFC (the rising blue line) and has underperformed since. At the end of 2022, the PE ratio for the emerging markets was 34% lower than the developed markets.

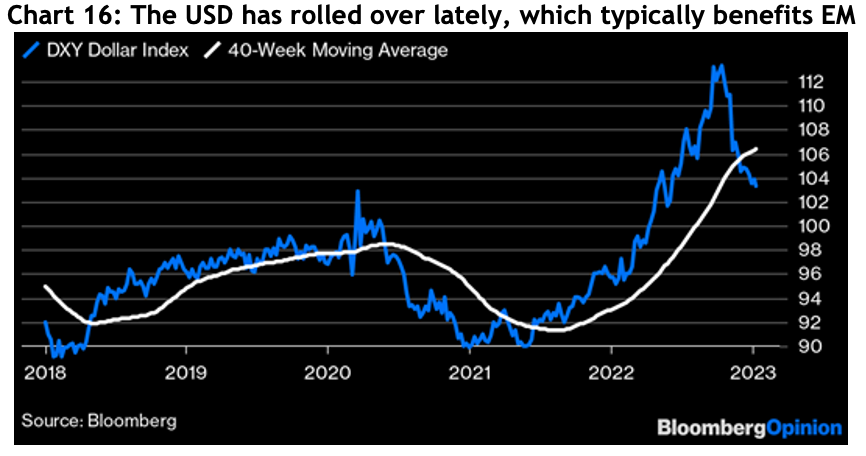

The emerging markets tend to do poorly when the USD strengthens, and it has just come off one of its strongest years ever, rising 22% at one point. Chart 16 shows the USD has rolled over dramatically, which should support EM.

Looking ahead

As always, there are compelling sounding arguments on both sides. On balance, it would be surprising to see economies fall into a deep recession when unemployment levels are at 50-year lows and household incomes are healthy. Inflation appears to be falling at a rate that would justify central banks pausing, or at least slowing, to see what effects the interest rate rises they’ve already pushed through will have.

Having endured some significant losses in 2022, global markets have started 2023 strongly. Indeed, the ASX has had its best start to the year since 1988, three quarters of stocks in the S&P 500 are more than 20% off their lows, Europe has bounced 20% off its lows and the UK is only 2% off its all-time highs.

We know when markets turn positive it can be difficult to put your finger on why it’s happening at the time, but then they tend to run hard as investors play catch up. There is no assurance we won’t revisit the lows, but it’s looking less likely and after a tough year last year, you can see light in the proverbial tunnel.

The views shared in this article are the author’s views and don’t necessarily reflect those of the whole firm.