Part 1

Conventional economics is having a really hard time explaining what’s going on in much of the world today: how can we have such low inflation when interest rates are at record low levels? How can some governments consistently run deficits, that look for all the world like they could never be repaid, and yet their bond yields are going down, not up? How come those economies where central banks have been pumping in stimulus for years, are still showing sluggish rates of growth?

The same questions have left many investors perplexed as asset prices stay high while they read about a range of risks.

It makes sense that if conventional thinking can’t explain what’s going on, then it’s time to look elsewhere. There is one school of economic thought that’s been talking about the inevitability of declining inflation and interest rates for years. It has not just a plausible, but also logical, explanation for many of the conundrums that leave orthodox economists scratching their heads.

However, that school of thought is so unconventional, and requires such a radical change to long-accepted wisdom, that those orthodox economists, including some of the best known names in the industry, have been lining up to ridicule it. But the most common criticisms sometimes show at best a lack of understanding, and at worst, an unwillingness to think differently.

That new school of thought is known as Modern Monetary Theory, which is commonly abbreviated to MMT. The first problem MMT has is its name, which is simply not a good description of what it is.

While it is indeed modern, having been developed in the early 1990s, it could easily be mistaken as a new version of ‘monetarism’, which was the economic theory developed by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School back in the 1960s that advocated, amongst other things, that markets are best at determining the optimal allocation of resources, so the role of government should be minimised and indeed fiscal spending is not only ineffective but irresponsible, because the resulting government borrowing will end up increasing interest rates, inflationary expectations, or future taxation in order to fund it.

But if that thinking’s right, then how is it that Japan and the US, both with massive government deficits, can reduce tax rates and have falling inflation and interest rates?

MMT is, in fact, the antithesis of monetarism, arguing governments must spend in order to achieve full utilisation of an economy’s resources. In that sense, it’s closer to Keynesianism. Finally, it’s not really a ‘theory’, it’s actually a straight up application of accounting rules to explain how money works in an economy where the government controls its own currency, in other words, an economy like Australia’s.

One of MMT’s most controversial insights is that such a government cannot be insolvent, that is, it can never run out of money, however, it can go broke. How that works is a government creates brand new money whenever it injects more in fiscal policy that it takes back in taxes, so, by logical extension, it can never run out.

However, that money is effectively backed by all the resources of the economy: all the workers, machines, factories and farms. If every single one of the workers suddenly disappeared, so there’s nobody left to run the machines, then the economy’s stuffed and the money is worthless. The government would be broke.

In this sense, one of the hardest lessons to get your head around that MMT teaches us, is that treating a government like it’s a household is fundamentally wrong. A household doesn’t control its own currency, so it can easily become both insolvent and broke. If a household spends more than it earns, or takes on too much debt, it’s in big trouble.

Because a government can create money at will, MMT points out that government spending is not constrained by a lack of funds. This is where conventional economists yell indignantly that MMT is preposterous: telling a government it can spend as much as it wants is a sure-fire recipe for inflationary disaster, and they’ll often refer to Venezuela, Zimbabwe or the Weimar Republic of the 1930s as examples of what happens when governments spend money as if there were no limits.

But MMT explicitly acknowledges the existence and risks of government deficits and inflation. What it says though, in a very simplified example, is imagine the economy is like a giant department store where both the private sector and the government sector shop for the things they need, everything from hospitals, to cars, workers, or soldiers. If some of the stock is not being bought by the private sector, that means there’s excess capacity and you’d expect prices will not be rising. It follows the government is able to go to the store and keep buying things with its printed money until all the stuff in the shop is being sold before you’d expect prices to rise.

One of the critical things to remember about MMT is it’s not a policy framework, it’s simply a model of how money works in a modern economy and this has been a very brief and basic overview of what is a complex and sophisticated body of work that’s gaining increasing traction as the most logical explanation of a variety of situations that conventional economics is at a loss to explain.

Part 2

In the first part of this overview of Modern Monetary Theory, I suggested it provides the most logical explanation of what’s going on in the world’s economies that conventional economics is simply at a loss to account for.

One of the unexplained mysteries is how countries can have the lowest interest rates in history, which is supposed to stimulate the economy, with low unemployment and yet economic growth is also, surprisingly, low.

Back in the early 1980s the US central bank ‘put the inflation genie back in the bottle’ by cranking interest rates all the way to 20%. Soon after that, governments the world over happily passed responsibility for managing economic growth to their central banks in the form of targeted inflation and unemployment rates.

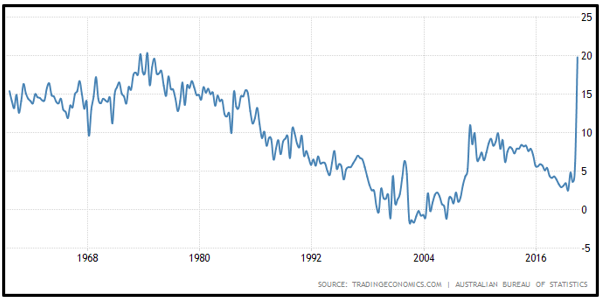

The problem is, central banks only have one weapon: short-term interest rates, also known as the cash rate. In an effort to stimulate growth over the past almost 40 years, central banks have been steadily reducing interest rates. Occasionally they’ve had to raise them when lending growth got out of hand, but the overall trend has been a steady decline.

The other side of this story is governments at the same time tried to minimise budget deficits, on the basis that conventional economic theory dictates it’s prudent economic management. However, another of MMT’s insights is that government spending creates money and activity. When a government spends more than it takes back in taxes, referred to as a budget deficit, it’s injecting money into the economy. But when it runs a budget surplus, it’s sucking money out of the economy, meaning the only way for the economy to grow is by the private sector making up for the reduction of government money in the system by running down their savings and borrowing money.

Here in Australia, the Howard government was lauded for running budget surpluses, so how did the economy grow so strongly over that period? In short, there was a credit boom. Household savings rates fell from 4% to -1%, and credit growth averaged around 12%, peaking as high as 16% in 2005. The result was household debt increased from around $200 billion to $900 billion, representing an almighty credit impulse to offset the lack of government spending.

MMT identified ages ago that relying on households to borrow in order to stimulate the economy will only work for so long, because eventually borrowing capacity maxes out and you’re left with the situation we have now, rates are the lowest they’ve ever been but credit growth is also the lowest since they started tracking it in 1977. Economists call it ‘pushing on a string’.

Not surprisingly, Philip Lowe, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, has been all but begging the government to crank up fiscal spending in order to support the economy. And he’s not the only one, central bankers across the world, acknowledging that monetary policy has reached the end game, have been calling on governments to start doing some of the heavy lifting by increasing fiscal spending.

The problem is politicians are stuck in the conventional economic mindset that presumes a government’s finances are the same as a household’s, which we learned above is fundamentally wrong, since a household cannot print its own money. A government that can print its own money is never financially constrained.

MMT does, however, acknowledge that a government is constrained by its economy’s total resources. Once government spending hits a level where it’s competing against private spending, prices will go up and inflation sets in.

Until that point, though, accumulated government deficits simply represent money the government has put into the economy that hasn’t been taken back out again by taxes. Another of MMT’s insights that conventional economists find hard to swallow, is that accumulated deficits don’t represent a burden on future generations that will result in crushing interest rates or catastrophically weak currencies as overseas investors refuse to fund our indulgent spending.

The best illustration of that is Japan, where government debt is 240% of GDP. As remarkable as it is, the government could print a ¥1,000,000,000,000,000 (that’s one quadrillion) yen note tomorrow and the debt will be instantly extinguished. Ah, but, the conventional economists scream, no one would ever trust the Japanese government again. Realistically, no one expects the government to repay that debt, ever, and it’s going up at about ¥1 million every two seconds! And yet the world continues to trade with Japan, the Yen is seen as a ‘safe haven’ currency and inflation has averaged around 0% for the last 25 years.

While MMT asserts government spending is not financially constrained, it also acknowledges some government spending is better than others. A big chunk of President Trump’s US$1.5 trillion of tax cuts went into the pockets of people who were already net savers, so the growth benefit was muted. That same US$1.5 trillion could have been used to eliminate student debt and almost all the money would have gone into the pockets of people who are net spenders, so the growth impact would have been far more pronounced.

Similarly, governments can spend on infrastructure, education, promoting R&D, or improving health, all things that underwrite long-term growth.

MMT uses iron clad rules of accounting to describe how government finances work, which is a such a radically different approach to conventional wisdom that it is understandably meeting stiff resistance, but if conventional thinking can’t explain what’s going on, then clearly it’s time to think unconventionally. With Australian households unable, or unwilling, to take on more debt to underwrite economic growth, and the Morrison government doggedly insisting it will deliver a budget surplus, the MMT school would be suggesting that does not auger well for a bright near-term outlook.