Australian investors love two things: property and banks. And why not, the returns from both have been spectacular over the last 30 years. Which is no coincidence, given the more money people borrowed to buy property, the better the banks did. But just as there are now strong arguments to be careful about investing in property, so too, there are plenty of questions hanging over the banks as profits get squeezed between falling revenues and rising costs and valuations are challenging.

The mutually beneficial relationship between Australia’s four big banks and the residential housing sector really kicked into gear in 1988, when the first Basel banking accord halved the amount of capital banks had to keep on their balance sheets against residential mortgages. Getting the same return on half the capital meant profitability doubled overnight, and not long after, Australian banks boasted the best Returns on Equity (a measure of profitability) in the developed world.

This rescued the banks after they’d suffered one of their worst periods in history, lending too much money in the 1980s to wheeler-dealers like Alan Bond and Christopher Skase. Given the higher profitability, not surprisingly, the banks did everything they could to push more and more debt into Australian households over the ensuing 30 years, which in turn fuelled house prices and saw home lending go from about one-third of the banks’ loan books, to now closer to two-thirds. It was a cycle that self-perpetuated: as property buyers borrowed more money, house prices went up and the banks made more money, and the banks’ shareholders made more money.

Banks do best when demand for loans is high, but in August year on year credit growth dropped to 2.9%, the lowest since the data started being recorded in 1976. That’s despite interest rates having fallen to their lowest ever and both the regulator and the government doing their utmost to encourage people to borrow. With mortgage debt having doubled in the 10 years to early 2019, Australian households are up to their proverbial eyeballs in debt, in fact we have the second highest level of household debt to GDP in the world at 120%. For context, the average for developed countries is 72%, and in the US it peaked in 2007 just before the GFC at 99% (it’s now 76%), Ireland peaked at 117% (it’s now 44%) and Spain at 85% (it’s now 60%).

In short, there’s just not a whole lot of room for residential mortgage debt to grow anything like what it has over the past 30 years.

Low interest rates are also hurting the banks. Over the past 20 years Net Interest Margins (NIM), which are essentially the after-costs difference between what banks charge borrowers versus what they pay depositors, have dropped by more than a third from 3.3% to 2.1%. Deposit rates are already very low (a quarter of Commonwealth Bank’s deposits are receiving 0.25% or less!), but banks are reluctant to reduce them much further because they’re dependent on deposits for a big part of their capital backing. That means the banks find themselves squeezed between the rock of eating into their margins whenever they cut mortgage rates, and the hard place of enormous government pressure to pass on the full RBA rate cuts.

Scott Olsson, the banking analyst at fund manager Firetrail Investments, points out that other revenue lines for the banks are under pressure as well. “The banks customarily invest their non-interest-bearing liabilities, which is about 15% of their asset base, in three and five-year bonds, the yields for which have fallen about 70% in the past 18 months.”

He also points out that about 25% of bank revenues are from fees and charges, and they’ve been under enormous scrutiny from the likes of the Hayne Royal Commission into banking misconduct. “Over the past 18 months CBA has cut about $400 million from that revenue line, and while the others haven’t been as transparent, the boards are certainly reacting to the regulatory pressure. We know Ross McEwan, the new NAB boss, cut fee revenue hard when he arrived at the Bank of Scotland and he may do that again, which would just increase the pressure on all the banks.”

Bank profits have also been flattered over the past 5 years by bad and doubtful debt charges running at 0.10-0.15% of total loans, compared to an average of 0.25% over the whole of the business cycle. That means at some point they will have to run significantly higher to hit that average, and Olsson estimates if CBA’s charge doubles, profits would fall about 10%.

The costs side of the ledger isn’t doing the banks any favours either. They’re all talking about having to slash costs, but as the old investment adage goes, it’s an unusual company that can cut its way to prosperity. Add to that the demand for increased IT spend, remediation costs for their wealth management divisions of more than $8 billion (so far) and the potential for regulators to require increased capital, and those tighter revenue lines are getting spread thinner and thinner.

As much as the banks hate cutting their dividends, those added demands on revenue have left them with little choice, and there could be more to come. ANZ cut its dividend in 2016, and earlier this year NAB cut its interim dividend by 16% to its lowest level in nine years. At its August result CBA had to increase its dividend payout ratio to maintain its dividend, and Westpac just announced a 15% cut in its final dividend with its result, together with a discounted capital raising to meet the regulator’s requirement of an ‘unquestionably strong’ level of tier 1 capital.

Margin and revenue pressures have translated into declining Returns on Equity (ROE). According to APRA, the banking regulator, only 10 years ago ROE for the four major banks was 20%, but by the end of June this year it was 11%.

Despite that, Australian banks are among the most expensive in the world on two of the most common bank valuation measures: price to book value and the price to earnings (PE) ratio. The big four banks are currently trading at an average of 1.6 times book value, which puts them bang on double the UK banks at 0.8 times.

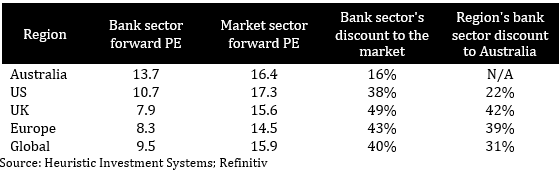

Australian banks are currently trading on a ‘forward PE ratio’, so how much you’re paying for the coming year’s earnings, of 13.7, a 16% discount to the overall market. The table below shows just how expensive that is compared to the rest of the world, where the global banks’ PE of 9.5 is 30% cheaper than Australia’s and sits at a 40% discount to the market.

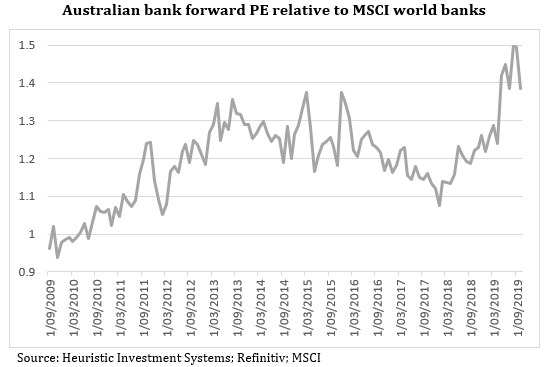

And the chart below also shows that, while Australian banks’ PEs have traded at a premium to their global peers for most of the last 10 years, it’s reached a new plateau. It’s a level that seems too rich for overseas investors, as Copley Fund Research recently reported that 91% of the foreign investors they survey have zero weighting to Australian banks, the lowest on record.

Australian investors have long loved their banks, but as Damien Hennessy, principal of Heuristic Investment Systems, points out “While it’s understandable local investors are attracted to the relatively high dividends, they need to be aware that Australian banks are expensive in both absolute and relative terms.” That doesn’t have to mean not holding any banks at all, it simply means be mindful of how much you do hold.