The 2020 recession, why this time is different.

There are number of things that make the global economic recession of 2020 different to any other we’ve seen, and while you’d never wish to go through an experience like it, there are definitely some silver linings.

The government forced the economy into recession

This was the first time in living memory that governments deliberately threw economies into recession. If you close down all but a few sectors and tell workers to stay home, obviously economic activity is going to crash.

Previous recessions have been attributable to the business cycle: typically there is a speculative build up which causes an imbalance that eventually tips over, and the worst recessions are those fueled by debt.

The standout example of this is, of course, the GFC. Building activity reached frenziewd levels in the US because buyers were able to access debt way too easily. The adjustment process was long and painful because credit, which is the lifeblood of a modern economy, all but seized up.

This time there were no baddies

When a recession is caused by excess building in some part of the economy, there is normally going to be a culprit you can point to. It might be banks, or it might be investors, but there’s a group that cops the blame and derision for crashing the economy.

That’s when the philosophy of ‘moral hazard’ argues if the culprits just get bailed out there’s no lessons learned to stop the same thing from happening again. Politicians and the media will often argue the responsible group should somehow be punished, perhaps with tighter regulations or even criminal charges.

This time (ignoring arguments about how COVID started and who or what is responsible), there is no real culprit to punish.

No holds barred support program

Because the government was responsible for switching off the economy and there was no concern about moral hazard, both they and central banks were able to throw the proverbial kitchen sink at supporting the economy.

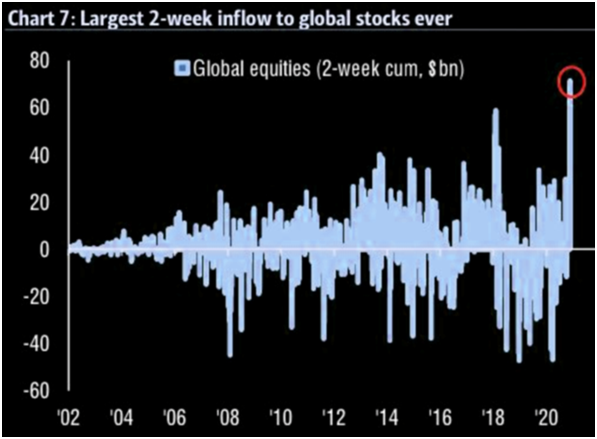

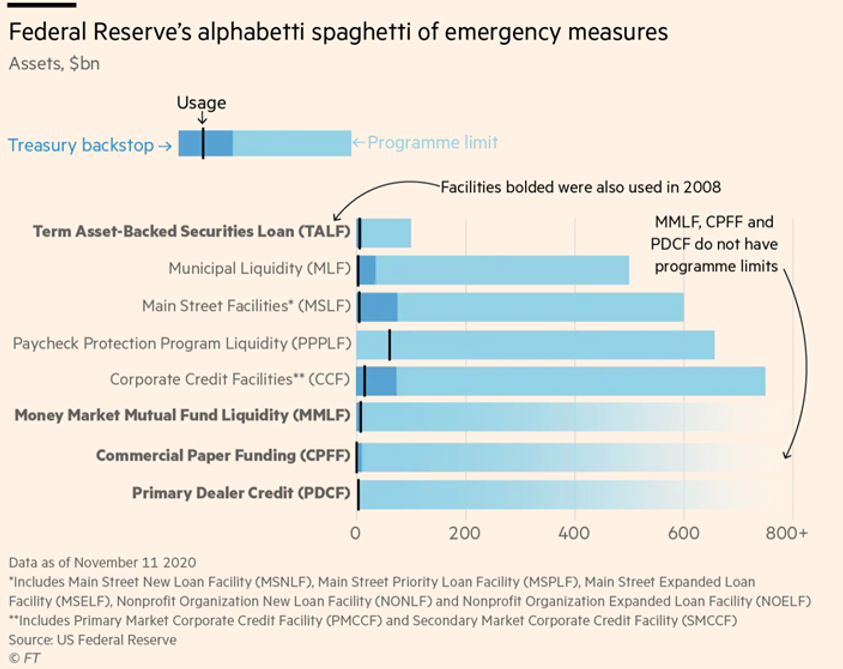

Central bankers learned valuable lessons from the GFC that they had to make sure credit could continue to flow. The range of measures undertaken was unlike anything we’d seen before, and while things were ugly for a short time, markets were once again reminded how powerful central banks can be.

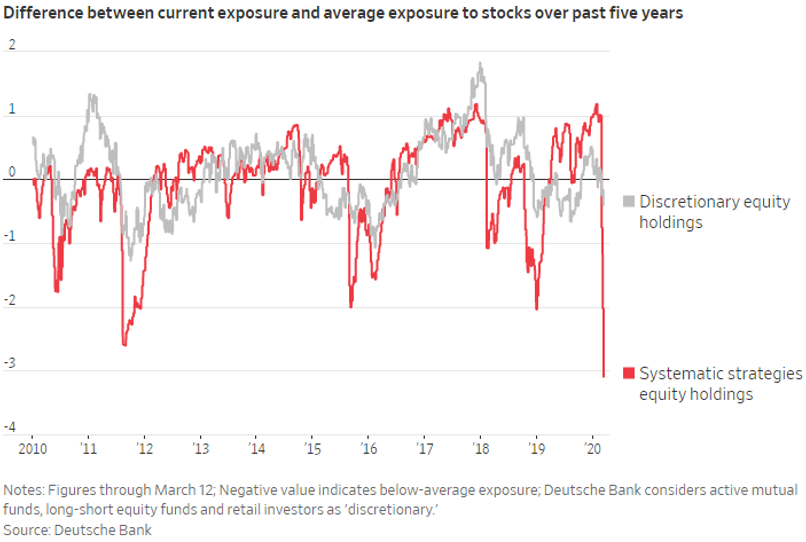

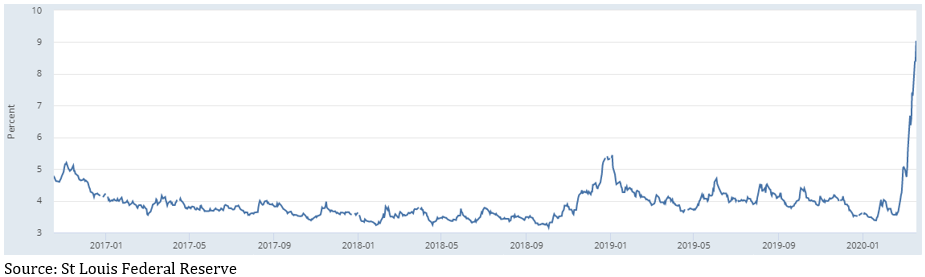

Remarkably, US financial markets have clearly recovered strongly despite the Federal Reserve barely tapping a range of the programs they announced – see chart 1 below.

Chart 1: US financial markets have recovered despite many of the Fed’s announced measures barely being utilized

The Bazooka

By far the most important support measures were from governments. One after another, governments wre throwing massive amounts of newly created money into their economies. Programs like JobKeeper in Australia and its equivalents overseas were critical in supporting families that otherwise would have been in dire financial circumstances.

The critical part is that it was newly created money, which governments can do directly, but central banks can’t. The central bank programs can help create new money by encouraging people to borrow (loans also create money) but that was going to be tough when the media was full of stories about the global economy crashing.

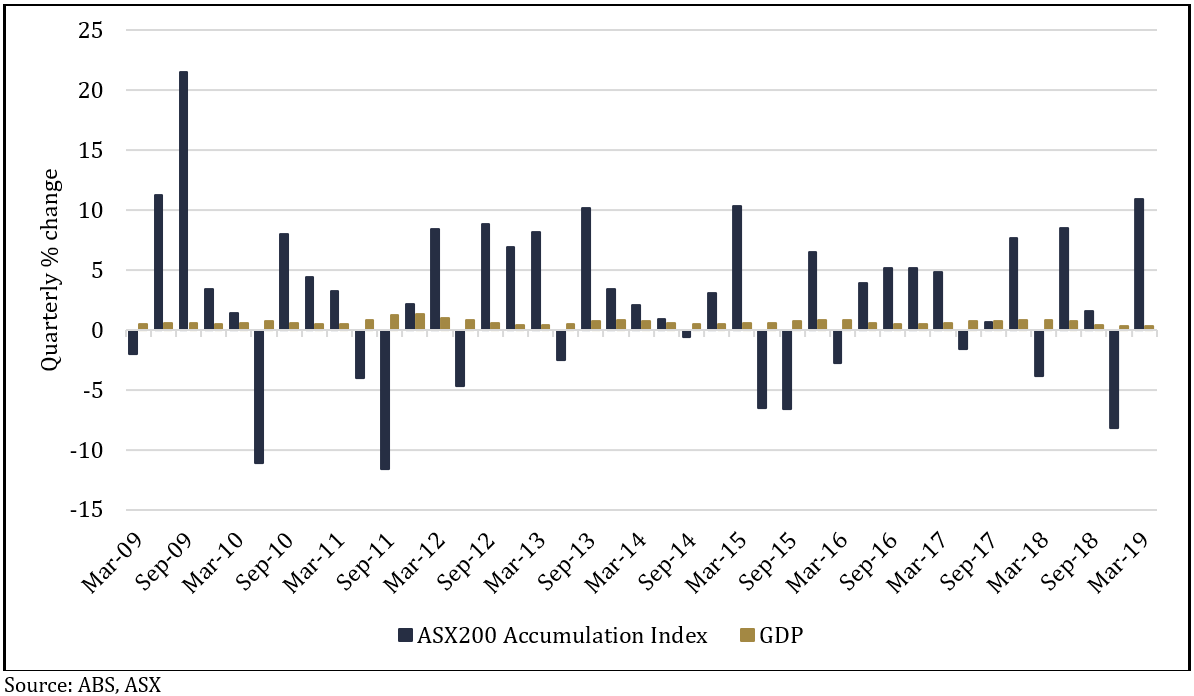

This is the opposite to what happened after the GFC, where, especially in Europe, governments preached from the gospel of austerity. Spending cutbacks sucked money out of economies and saw them slow to a grinding crawl.

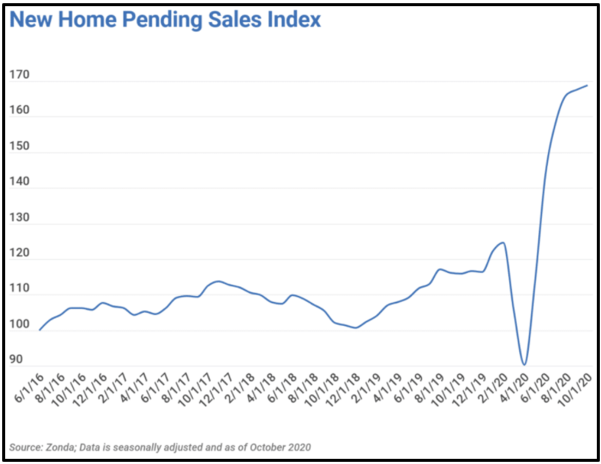

Economies are on fire

Some of the data showing how sharply economies are bouncing back is remarkable. Here in Australia, we’re seeing restaurant bookings up to 50-80% compared with the same time last year, new car sales leaped 12% from last year and Commonwealth Bank credit card sales were up 11%. They are huge numbers and it’s not just because lockdown restrictions were eased.

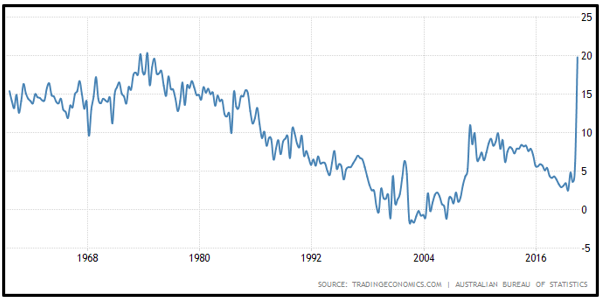

The Australian government’s COVID support programs amounted to 13% of GDP. It’s hard to overstate how massive that is. In the wake of the GFC, the Chinese government ‘rescued’ much of the developed world by announcing a spending package equivalent to 12% GDP (clearly the absolute amounts are hugely different, it’s the proportion that’s significant). The early withdrawal of superannuation adds anotehr 2% to that. The household savings ratio hit almost 20% in the June quarter, only a fraction less than the highest it’s been in the past 60 years.

That’s an awful lot of pent-up spending power.

The silver lining

Ever since the end of the GFC, central banks have pleaded with governments to raise fiscal spending to help increase economic growth. But most governments, including Australia’s, were obsessive about balancing budgets and instead were more intent on reducing spending (the obvious exception to that was $1.2 trillion Trump tax cuts, which helps explain why the US economy was doing so much better than most others).

It’s taken the unique circumstances of the pandemic to show the power of fiscal spending to drive economic activity: low income families suddenly had enough money to go to the dentist and get the car fixed, and the money they spent doing that got spent again and again.

If governments take the lessons on board, it’s possible it could be the first step toward abandoning the flawed dictums of neoliberalism and addressing the massive wealth inequalities that lie at the heart of so many other problems we face. That would be a great silver lining.

Want to take advantage of the expected economic growth?

Call Steward Wealth today on (03) 9975 7070 to learn how.