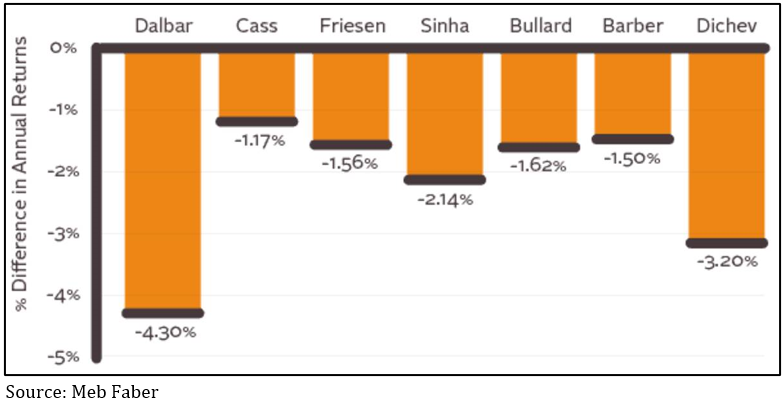

A classic mistake

What would you do: you’re 67 years old and about to retire from General Electric with a company pension. You hold US$1.8 million worth of GE stock, which accounts for 90% of your investment portfolio. Do you sell some of your GE and diversify or sit on it because it’s a blue chip company?

This was a topic discussed on a recent episode of one of my favourite podcasts, called Animal Spirits, where two American financial bloggers chat about things they’ve found interesting over the past week. It was actually a thread on Reddit posted by the retiree’s son, who was asking what his dad should do having held the shares for years and being “quite stubborn”, which presumably means he wanted to hang on to them.

There were some 124 comments on the post. While I haven’t read all of them, my sense is that most were arguing he should keep the shares, with quite a few pointing out the 4% dividend yield would pay him US$72,000 per year. I’ve no idea what the guy ended up doing but, given what’s happened to GE shares in the nine months since, there’s a really good lesson to be had for anybody.

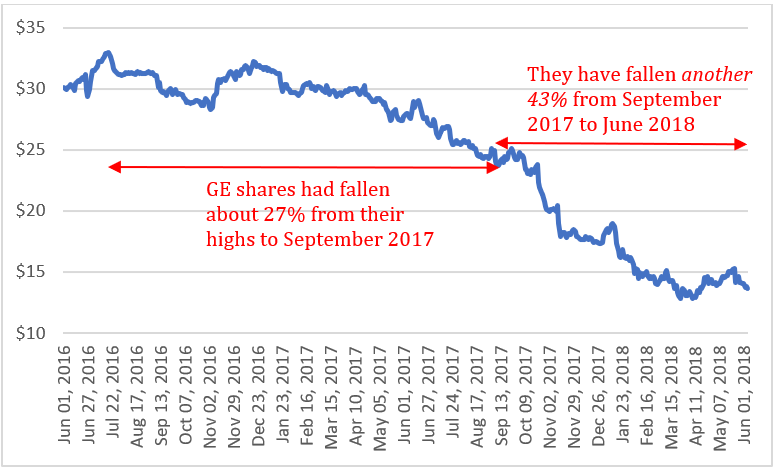

When the original question was posted in September 2017, GE shares were trading at around $24, having fallen about 20% in the previous year and compared with a peak of about $33 in July 2016. GE has been one of the great blue chips of the American market, so it’s not surprising that a lot of people expected it would rebound. Alas, today the stock is trading around US$13.60 after revealing problems with its power generation division, amongst other things, and cutting its dividend in November 2017 – see chart 1.

Chart 1: the GE share price has fallen more than 40% since September 2017

Source: investing.com

So if the retiree didn’t sell any of his shares, the holding would now be worth just over US$1 million and at the current yield of 3.5% he’d be receiving around US$35,000 in dividends.

So lesson number 1 is concentration risk. This guy had 90% of his investment portfolio tied up in a single stock, which is also the company that’s going to be paying his pension. That’s an awful lot of exposure to have to a single company, blue chip or not.

It’s often said it takes concentrated exposure to get rich, but you diversify to stay rich. While we can all name exceptions to that rule, when you’re that close to retirement the way the equation stacks up is very different to when you’ve got 20-30 years of work ahead of you.

Lesson number 2 is about what’s called ‘sequencing risk’, which is taking a big hit to your assets when you’re not going to be able to make up the lost money through work. He needed to do the sums: his total investments were worth US$2 million, plus he was going to get a pension. Could that amount of money have supported the lifestyle he wanted in retirement? If the answer is yes, then it makes sense to take steps to protect the capital, if it’s no, then how much more money do you need and what’s the best way to get there?

Just as importantly, he needed to ask himself how he would feel if the total of his investments dropped to US$1.8 million, or US$1.6. If the answer is he would have felt pretty miserable and stressed about the future, again, he needed to protect the capital.

When you’re about to retire is not the time to take the attitude of ‘those shares have fallen so far already, surely they won’t fall further’. Any share can go to zero, even those considered to be blue chips, just ask holders of Enron shares. And while of course there may be tax considerations in selling a big holding, it is risky to allow tax to be the main determinant of your investment strategy.

This scenario is yet another example of where our human biases can get in the way of making sensible decisions. It’s also another example of where it can be a good idea to get objective advice.