Low inflation explains everything

Low inflation is a global phenomenon that has central bankers tearing their hair out: nobody can tell you exactly what’s causing it and, so far, nothing seems to be able to stop it. And its effects on financial markets, and therefor every investor’s portfolios, are profound. In fact, this very low inflation environment can explain an awful lot of what seems to be peculiar in markets at the moment.

Just how low is inflation?

Australia’s ‘core CPI’, which excludes the more volatile prices like food and energy, averaged 3.7% since 1983, compared to the June reading of 1.6%. That’s not far off one-third of the average.

The poster child for low inflation is, of course, Japan, where, over the past 20 years, the core CPI has averaged -0.2%.

Lower bond yields

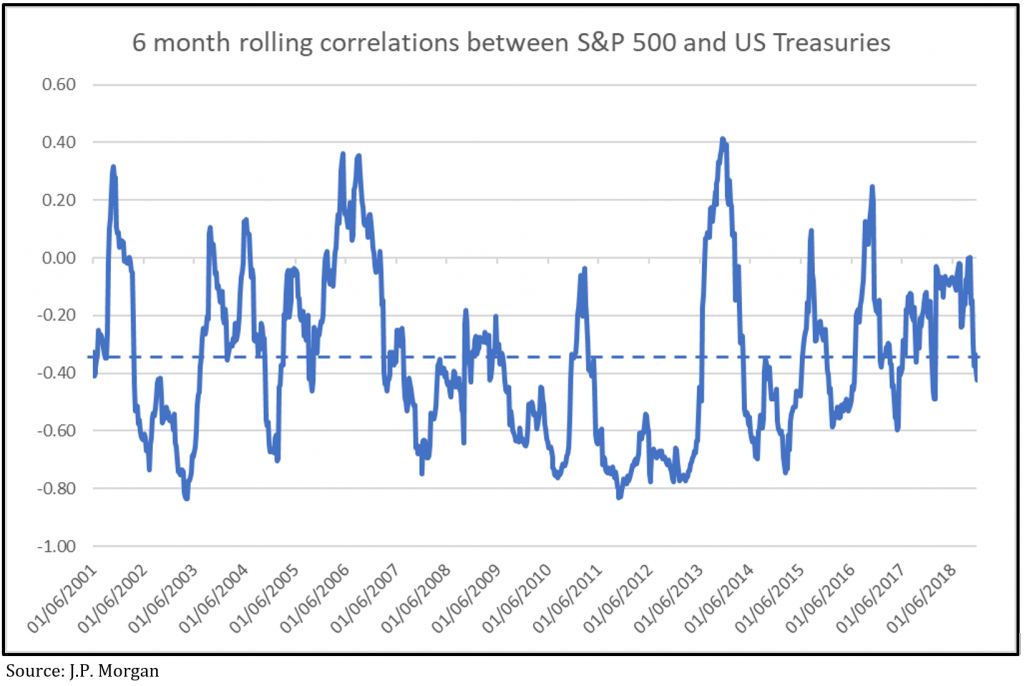

Inflation is like kryptonite for bonds: the higher inflation is, the weaker are bond prices, and vice versa. Across the world bond yields are plumbing record lows, including Australia where our 10-year bond yield is comfortably (or is that uncomfortably?) below 1%.

You might read how low bond yields indicate the bond markets are pricing in disastrous economic growth scenarios. In fact, what they’re pricing in is low inflation, and conventional economics dictates that you only get low inflation as a consequence of low economic growth. That may or may not happen, the truth is, nobody knows.

It can explain negative bond yields

There are experienced bond fund managers saying negative bond yields make no sense at all and pointing the finger at ‘central bank manipulation’. Bond markets are massive, reflecting the wisdom of a very big crowd, and they’re driven by a combination of human sentiment and some pretty funky mathematics.

If an investor has a view that disinflation (where inflation rates decrease over time) is here for the foreseeable future, then it’s perfectly rational to prefer the certainty of losing 0.4% of the value of their capital by buying a negative yielding bond, than sticking it under the mattress and losing 0.5%.

It can explain rising equity valuations

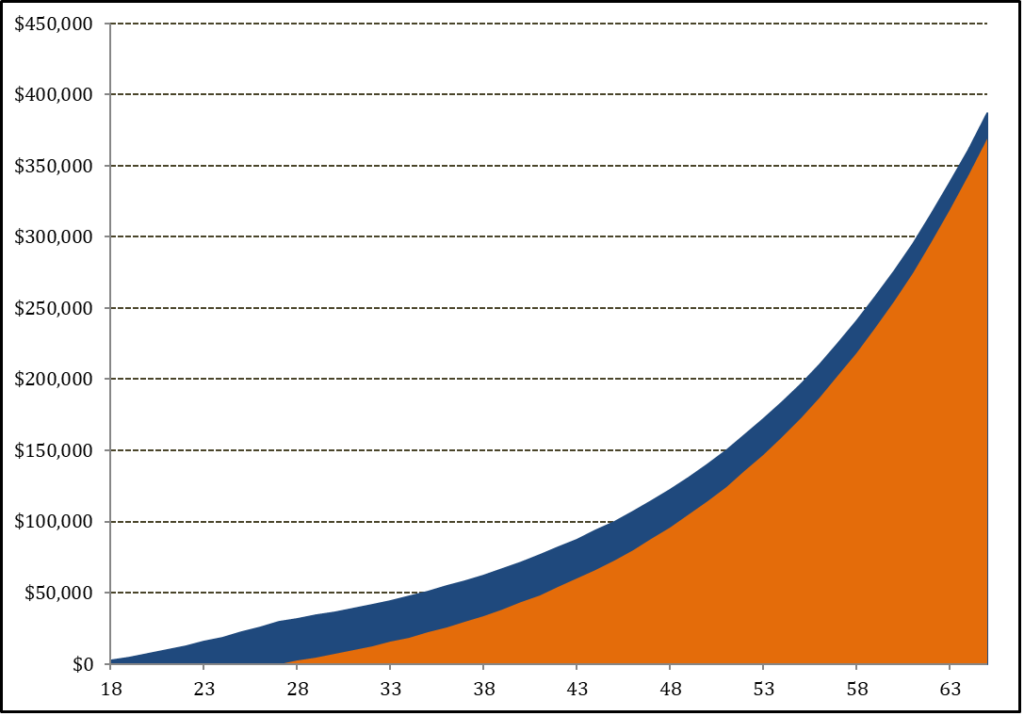

Investing 101 will tell you that a share price is supposed to reflect the net present value of a company’s future cash flows. To make that calculation you need to use a ‘discount rate’ that you apply to those future cash flows so you can work out what they’re worth in today’s money, the lower the discount rate the higher the valuation in today’s money.

That discount rate will normally be based on the ‘risk free rate’, which is typically the 10-year bond yield, but most analysts will add a bit extra to account for what they think might happen to bond yields going forward, or to reflect what they reckon might be added risks associated with the company they’re analysing.

In a recent interview, the well-known Magellan fund manager, Hamish Douglass, explained how small changes to your discount rate can have a magnified effect on a stock valuation: by reducing your risk free rate from 5% to 4%, the valuation of a business with 4% earnings growth increases by almost 20%, and a reduction from 4% to 3% sees a 25% increase.

Nothing else has changed, just your view on how long inflation will stay low, but now you’re prepared to pay significantly more for the same share. No wonder a talented fund manager friend of mine likens a DCF valuation to the Hubble telescope, where the tiniest shift can have you looking at a whole new galaxy.

Now imagine the pressure on fund managers across the world this year, with bond yields grinding downwards, forcing them to wrestle with whether or not they lower their discount rate and increase their valuations.

It can explain why so many fund managers have underperformed

Over the past nine years, so-called ‘value’ stocks have substantially underperformed ‘growth’ stocks, for example in the US by almost bang on 100%.

It’s probably not a coincidence that, according to Mercer, in the 2019 financial year, 87% of large cap Australian equity fund managers underperformed the ASX200, and in the 2018 calendar year it was roughly the same in the US. Not surprisingly, you’ll also read confounded fund managers, sounding like jilted lovers, complaining that markets are super expensive and being driven by a narrow cohort of sometimes defensive and sometimes growth stocks.

The problem is, if your frame of reference for valuations is the last, say, 40 years, you’re comparing a time of radically different inflation rates and bond yields – and therefor valuation metrics. It would not be surprising to find a lot of those underperforming fund managers are either resolutely (stubbornly?) sticking to their higher discount rate valuations or chasing their valuations higher as they begrudgingly accept lower and lower bond yields.

Those fund managers complaining about markets being expensive may end up being right, maybe inflation will go up and things will look like they used to once again, a process they call ‘normalisation’. Then again, maybe it won’t, and they’ll be left failing to adapt.

How long will low inflation last?

Because we can’t be sure of what’s caused inflation to be so low, nor can we be sure of how long it will stay that way. Who knows, this time next year we might look back wistfully on the days when we worried about inflation not being high enough, or in 10 years we may look back on the days when inflation was positive.