No need for investors to fear QE taper

At last month’s Portfolio Construction Forum summit in Sydney, almost every presenter – from economists to fund managers – was critical of central banks for “artificially inflating asset prices” with “excessive liquidity”, leaving financial markets “addicted to easy monetary policy”.

Indeed, US journalist Christopher Leonard recently published a book called The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the US Economy, which “tells the shocking, riveting tale of how quantitative easing is imperilling the American economy”.

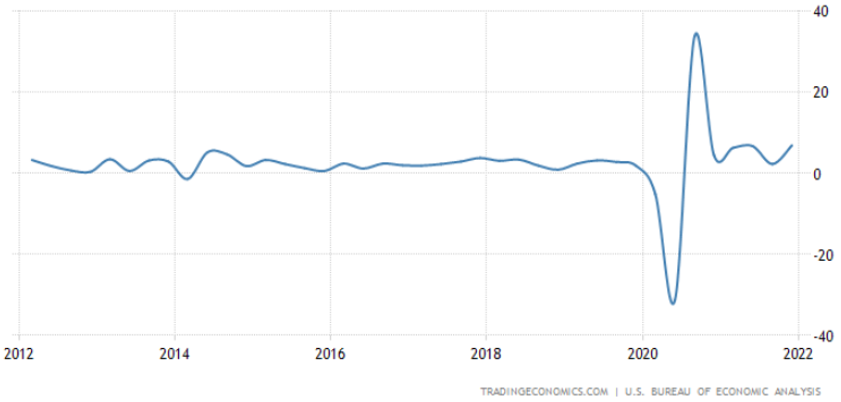

On the face of it, the numbers are confronting. Before the start of the COVID-19 crisis in February 2020, the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet stood at $US4.4 trillion. Two years later, after a program of buying government bonds and mortgage-backed securities known as quantitative easing (popularly referred to as QE), it has more than doubled to $US8.9 trillion ($12.3 trillion).

Similarly, the Reserve Bank of Australia has also conducted its own QE program, expanding its balance sheet from $180 billion before the pandemic to about $650 billion.

It sounds intuitive and seductively simple: central banks print money; they’ve expanded their balance sheets by trillions of dollars; all that newly printed money has inflated asset prices. Unfortunately, it is dead wrong but, as is often the case in financial markets, it’s the prevailing narrative that’s been repeated so often that people believe it.

In his book, Leonard describes how, under the QE program, the Fed will buy bonds off a bank by crediting that bank’s “reserve account”, which, in simple terms, is a special account that only banks who transact directly with the central bank can have. He then claims those banks are free to use those reserves “to buy assets in the wider marketplace”.

That just isn’t how it works.

What really happens is far more complicated, and far less exciting. Those reserves, which in Australia are called exchange settlement reserves, are a special kind of currency that is only transacted between the central bank and other commercial banks to make sure the billions of transactions the banks undertake daily settle every day. Those reserves are not the same as the cash used in the real world.

Central banks will also buy bonds from other institutions that don’t have a special reserve account with them, in which case they do settle with normal cash. However, according to the Reserve Bank’s website, those institutions are all credit unions, smaller banks or insurance companies. If an institution like that is holding bonds in the first place, which are classified as a defensive, fixed income asset, it is pretty much guaranteed they are not going to take the money and punt it on cryptocurrencies.

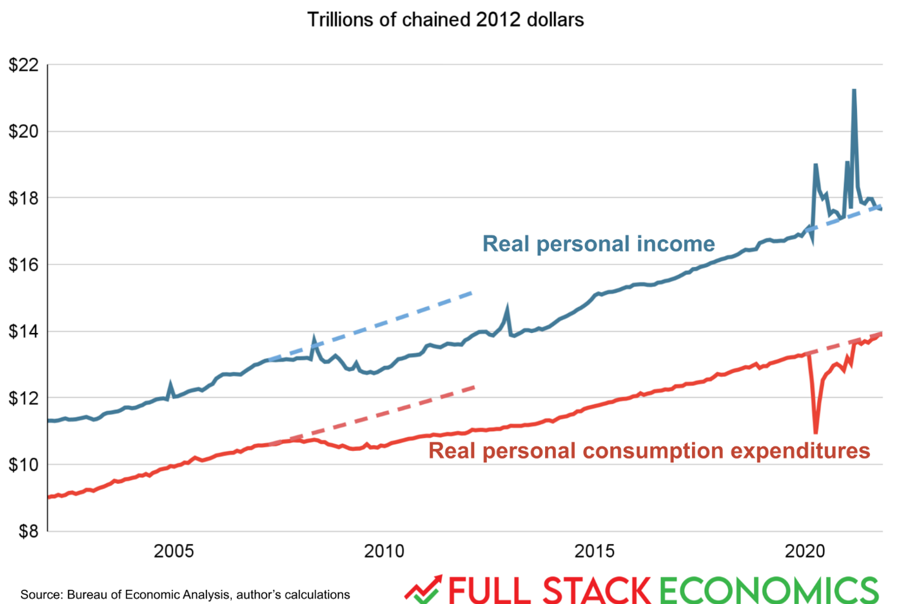

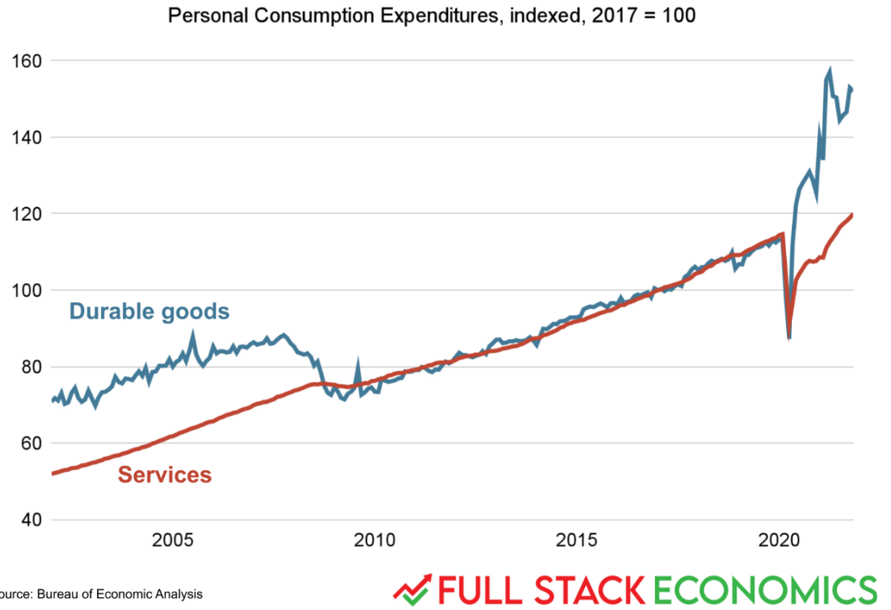

So what caused financial markets to rebound so aggressively if it wasn’t central banks printing money? It was governments, by injecting trillions of dollars, pounds, euros, yen and other currencies into economies to support them during the COVID-19 crisis.

That money was created out of thin air and is still circulating around their respective economies. In fact, governments create money in a keystroke via fiscal policy every day, with things like social security payments or any other spending program.

Many will argue it was central bank QE programs that allowed governments to run deficits – but this is not true either. Just like before QE, it’s the government spending money into existence that provides the cash for banks and others to buy the bonds. Central banks are not required to do anything other than conduct their normal daily monetary operations of targeting interest rates.

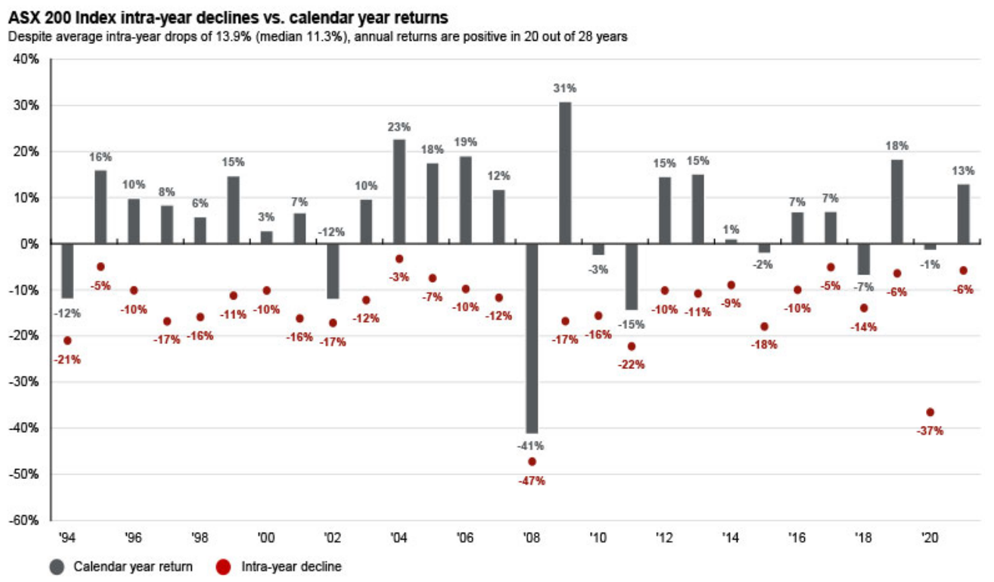

That the central bank QE programs did not drive the share market means the tapering of QE, or allowing their balance sheets to shrink, does not necessarily have a negative impact on the share market.

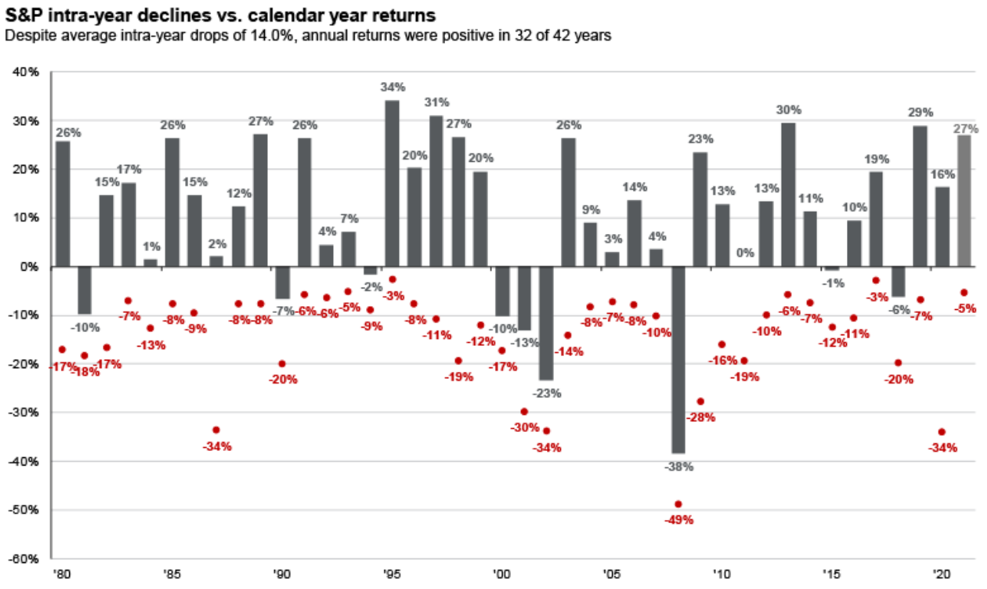

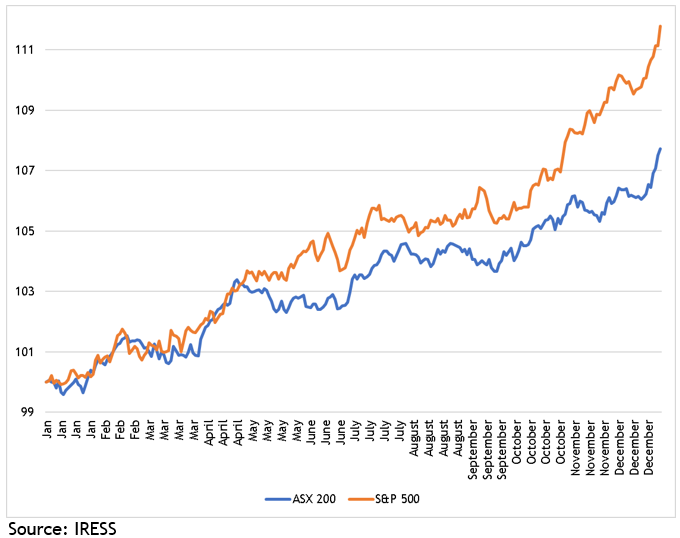

Chris Bedingfield, a portfolio manager at Quay Global Investors, points out that in the first three QE programs, the S&P 500 went up by an average of 2.2 per cent in the month after a QE “event”, be that the commencement, announcement of tapering, or conclusion of QE. On average, regardless of whether the announcement indicated an easing or tightening of central bank policy, a month later US equities were higher.

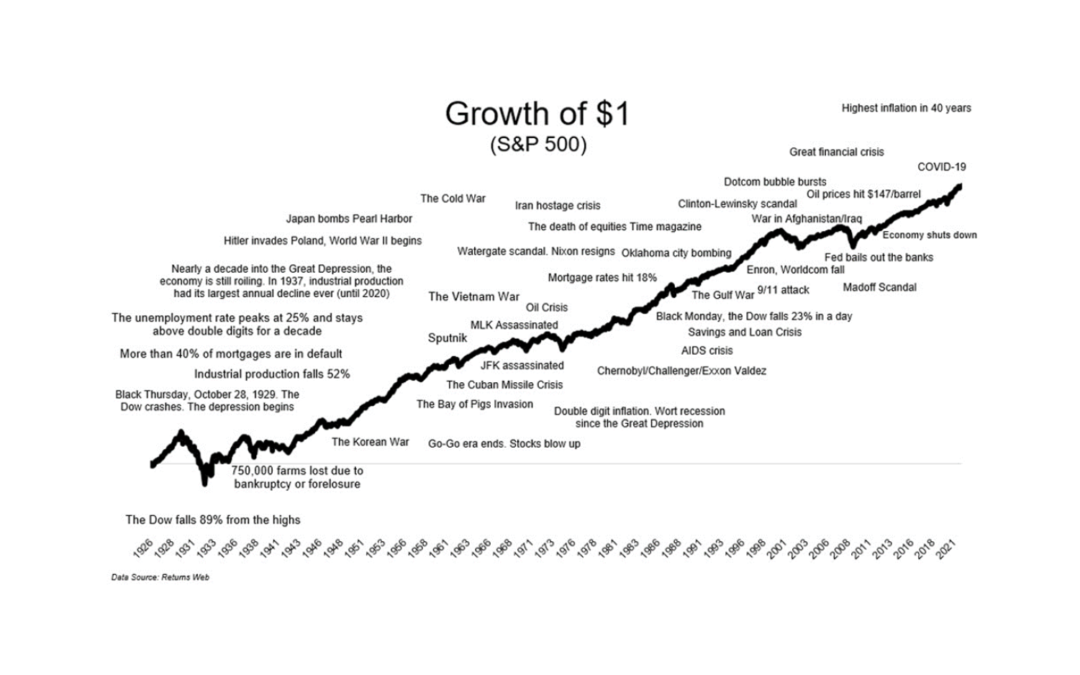

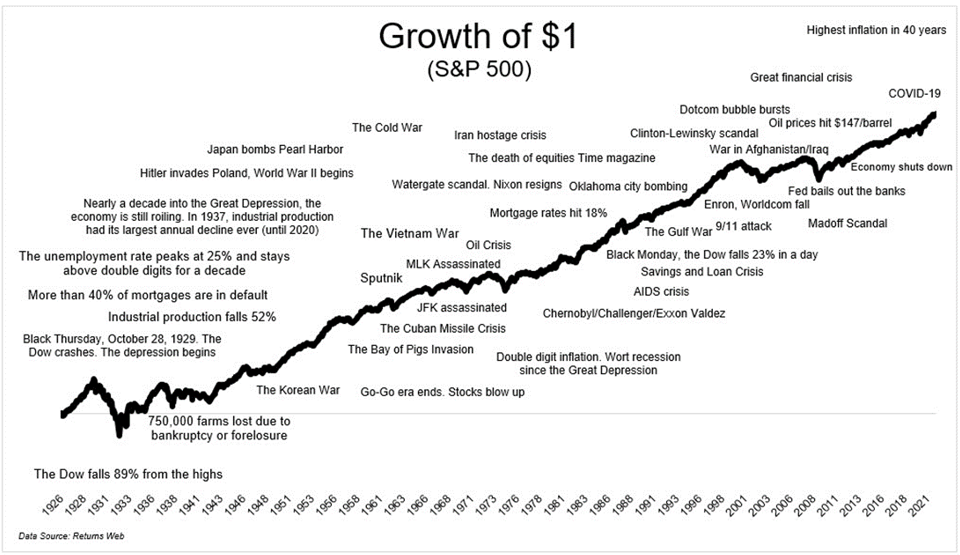

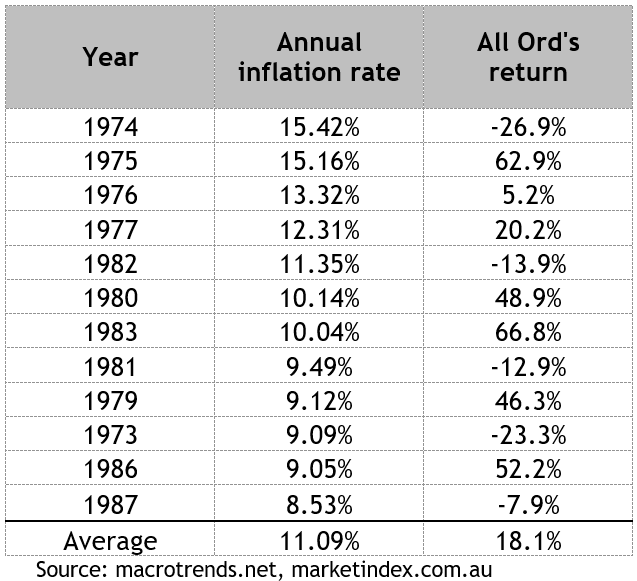

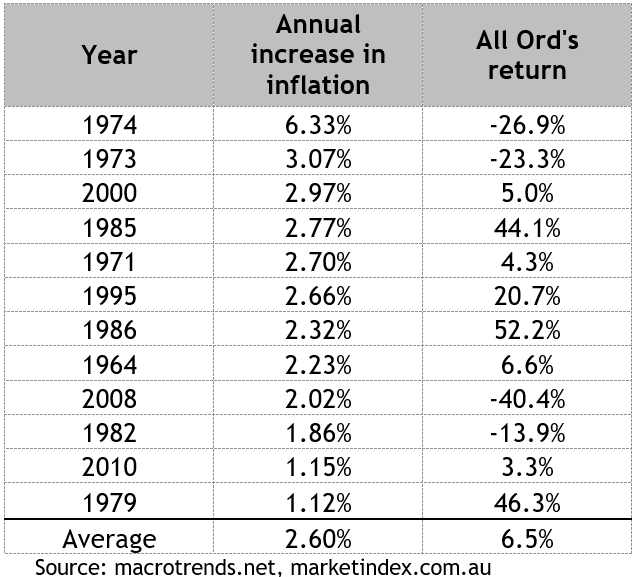

That does not mean share markets cannot fall – but if they do, it will have more to do with other factors, like valuations, fear, geopolitics or even inflation rather than central bank actions.