AI: boom, bubble or both?

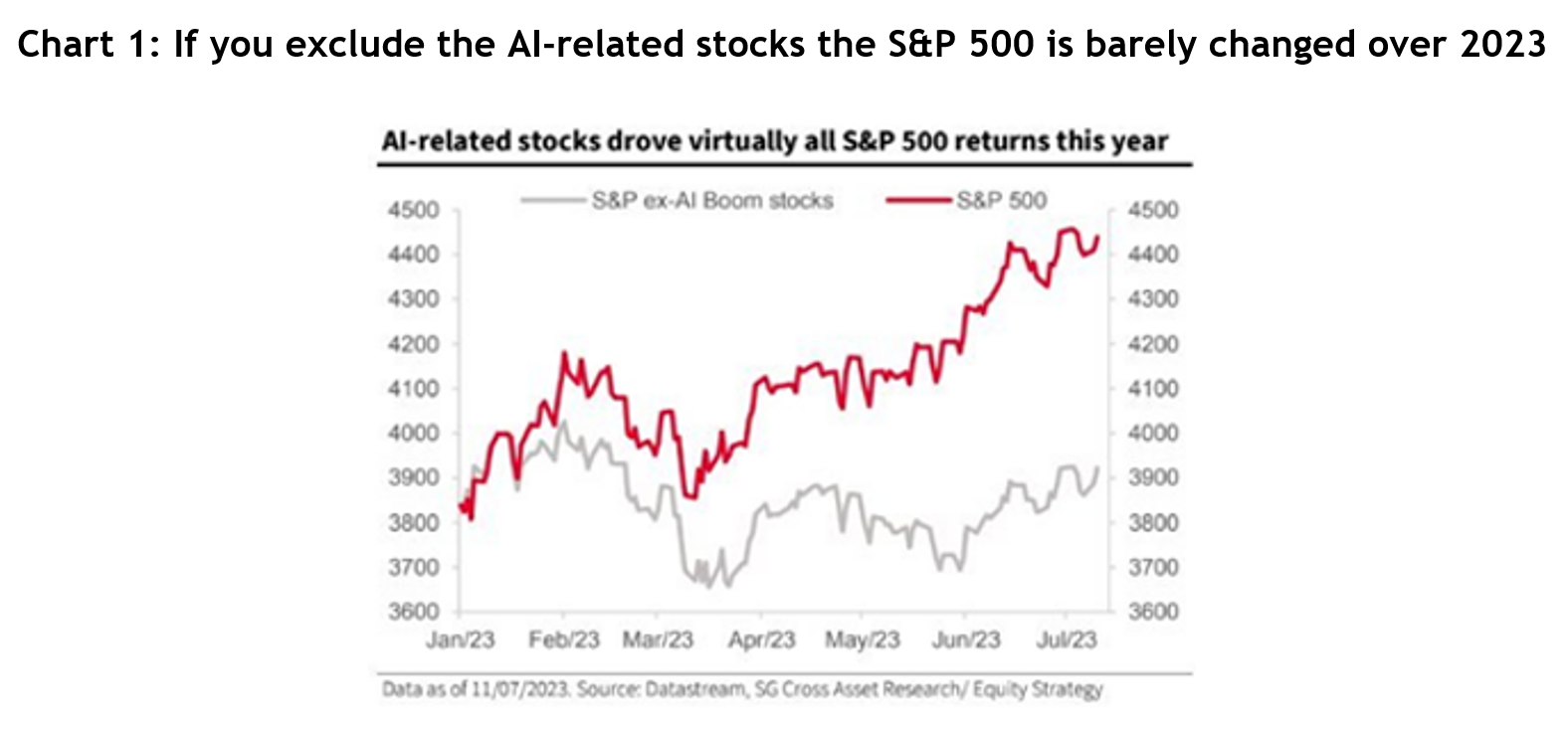

Over the first half of this year the US’s tech heavy NASDAQ index had one of its best ever starts to a year, rising 32 per cent and even the much broader S&P 500 rose a barnstorming 17 per cent.

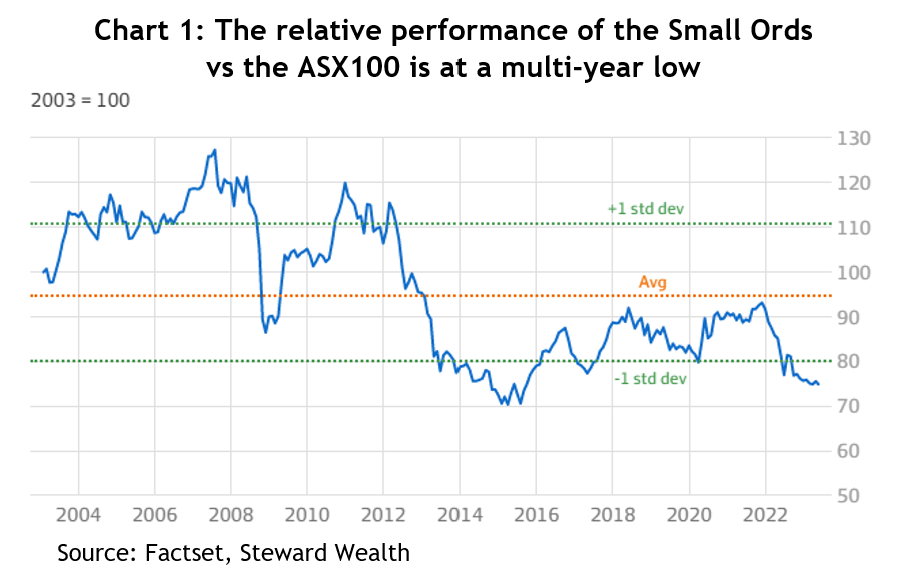

Investors could understandably be left wondering how the share market could be so positive when the vast majority of economists were still forecasting a US recession. While there’s always a bunch of reasons for why markets move the way they do, a huge component was the excitement generated by Artificial Intelligence, usually known by its shorthand of “AI”. In fact, SocGen calculated that if you strip out the AI-related stocks, the S&P 500 was only up by about 2 per cent over those six months – see chart 1.

As often happens with new technology there’s no shortage of controversy around AI, but no lesser than legendary Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen wrote, “AI is quite possibly the most important – and best – thing our civilization has ever created, certainly on par with electricity and microchips, and probably beyond those.”

Not surprisingly, analysts are falling over themselves trying to work out the implications of AI on company productivity and earnings, but at such an early stage anything they say is no better than an educated guess. It’s little wonder then that comparisons can be drawn to the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, when the whole world got swept up in the heady possibilities of the internet, and we know how that ended.

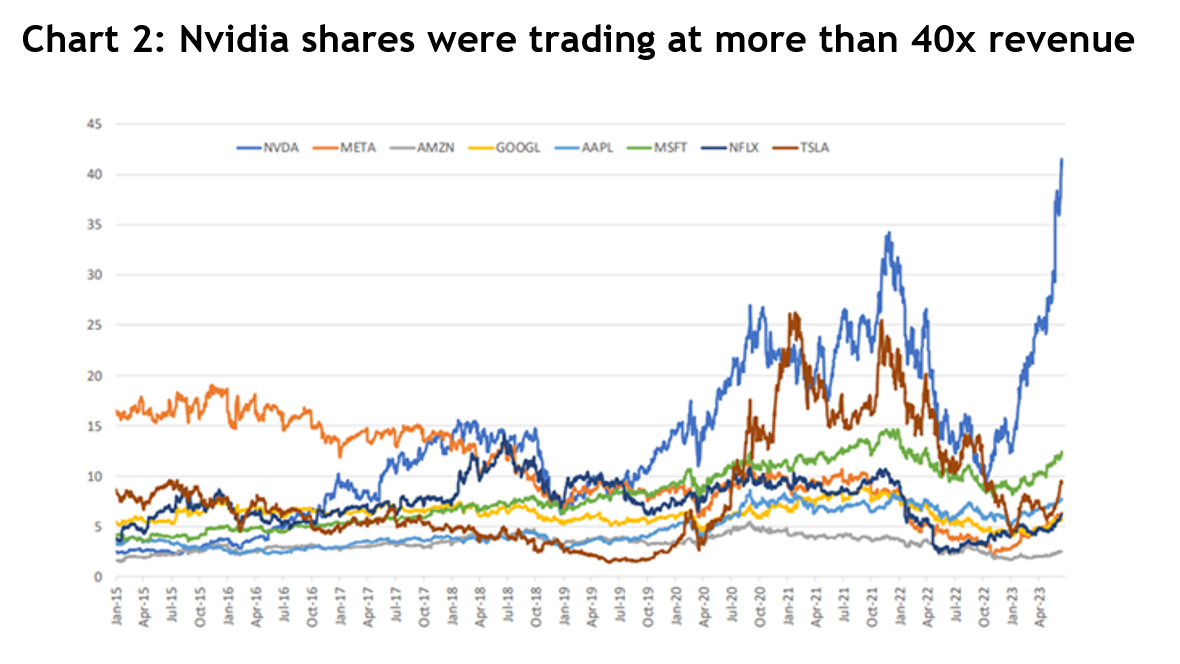

The AI boom really took off in late May after AI’s pin up child, Nvidia, not only reported first quarter earnings 20 per cent above analysts’ forecasts, but also increased its second quarter revenue forecast by a mind-popping 50 per cent – all due to AI demand for its computer chips. The shares jumped 26 per cent that day and rose a staggering 190 per cent in the first half of 2023.

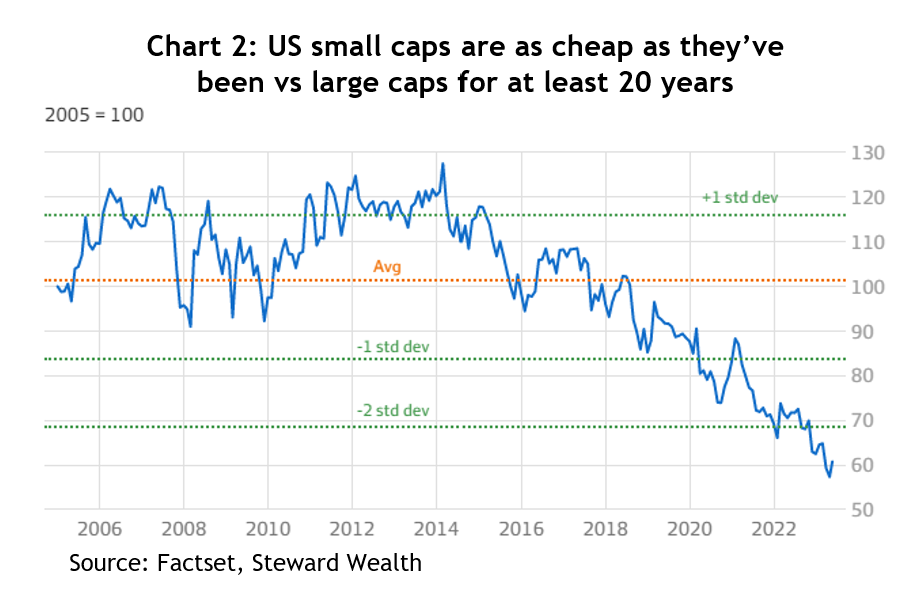

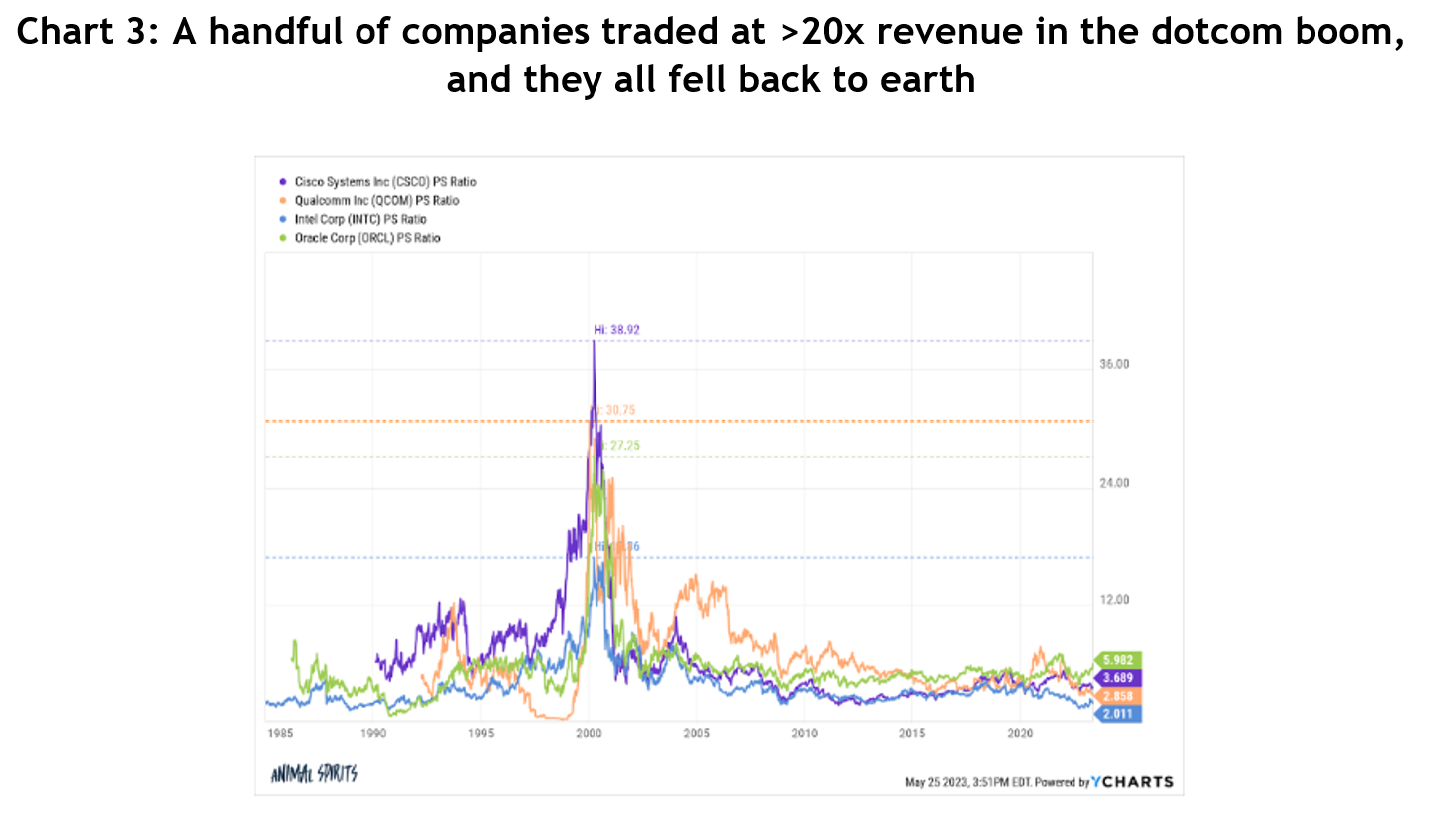

So here’s the ‘but’: Nvidia shares are trading around 40x revenue. That’s not earnings, it’s sales, before costs – see chart 2. There was a handful of companies that traded on similarly high price to sales ratios in the dotcom boom and they all came back to earth – see chart 3.

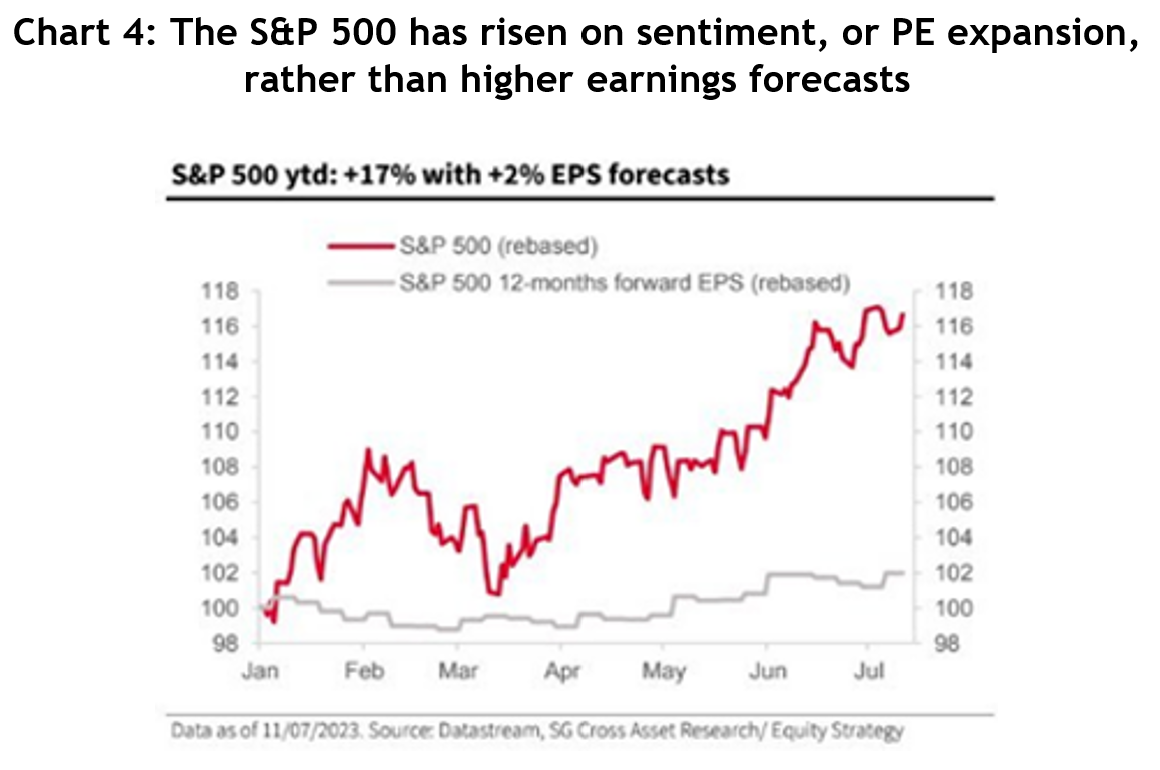

The rise in the US indices has been driven almost entirely by sentiment, the technical name for which is ‘PE expansion’. Theoretically, share prices should go up in line with the net earnings of companies, but sometimes markets get carried away over the short-term, especially when a new paradigm arrives.

Analysts currently forecast earnings will rise by 1 per cent in 2023, so the 17 per cent rise in the S&P 500 so far reflects the optimism being priced into AI – see chart 4. Share markets are always forward looking, but while the forecast for 2024 is for a respectable 12 per cent earnings growth, the S&P is already trading on a PE of 19x, a 27 per cent premium to its 20-year average of 15x.

There are some other signs of a frothy market:

- The forward PE ratio for the MSCI World Tech sector relative to the rest of the market is more than two standard deviations above its 20-year average, i.e. it’s really high – see chart 5.

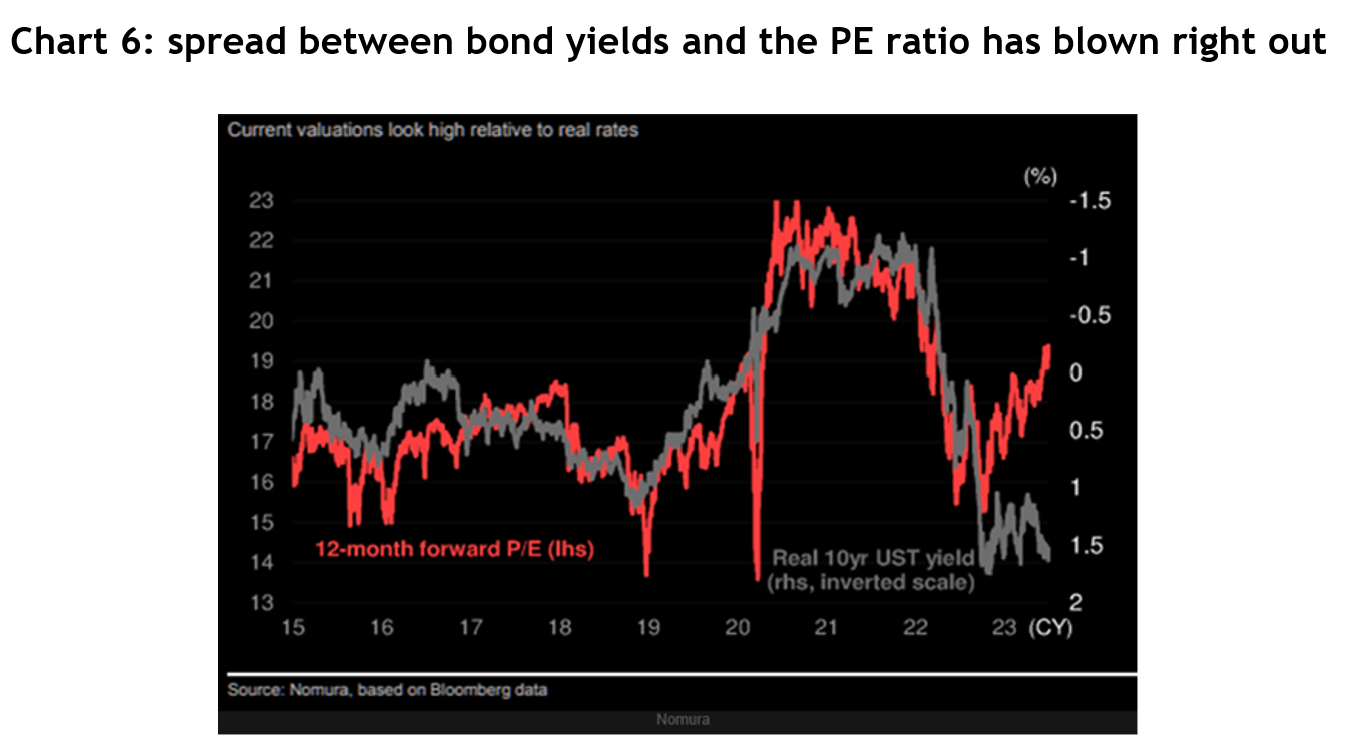

- Very low bond yields and inflation pre-COVID supported higher PE ratios, especially for the growth-oriented tech companies. But now the gap between the US real bond yield and the S&P 500’s forward PE ratio has opened right up – see chart 6.

- The S&P 500 is more than 8 per cent higher than what strategists, on average, guessed it would be by the end of year, which is the second largest overshoot in 24 years.

- Two of the best performing groups in the US year to date are non-profitable tech (+32 per cent) and the infamous ‘meme stocks’ from 2021 (+63 per cent).

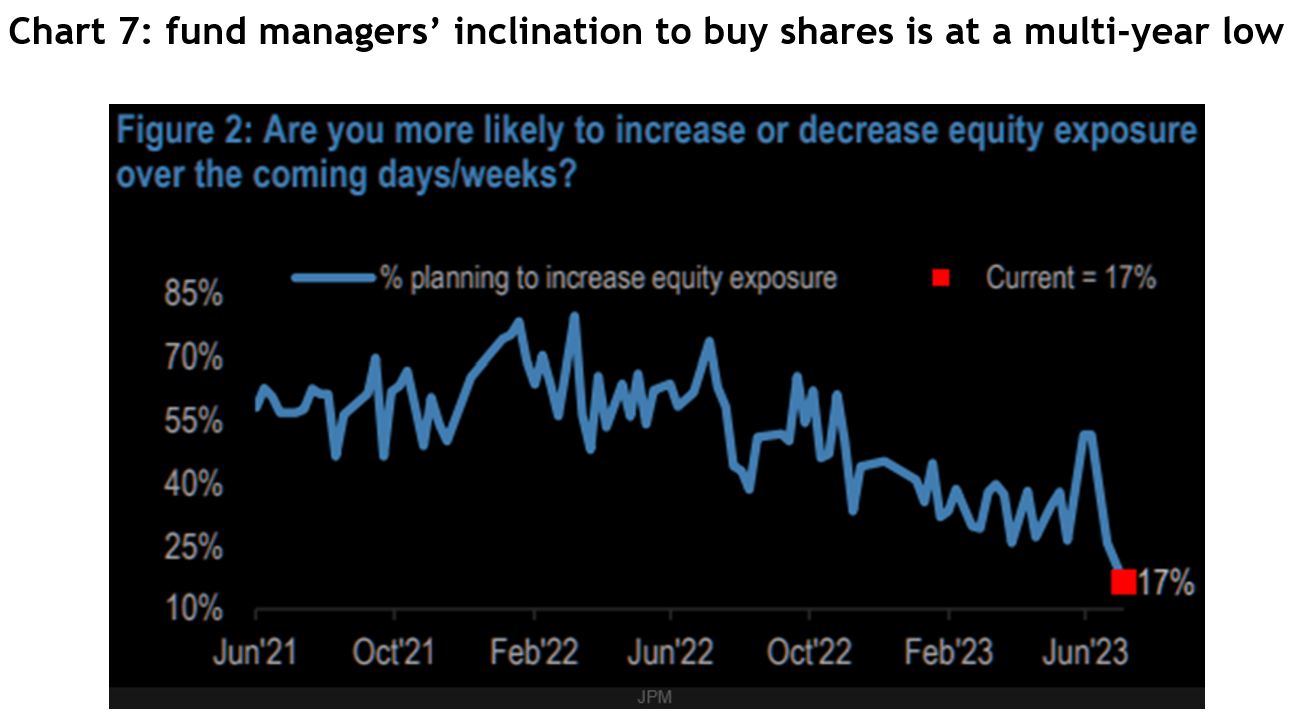

- The weekly J.P. Morgan fund manager survey reported only 17 per cent of managers were planning to increase their equity exposure over coming weeks, down from 50 per cent at the end of May.

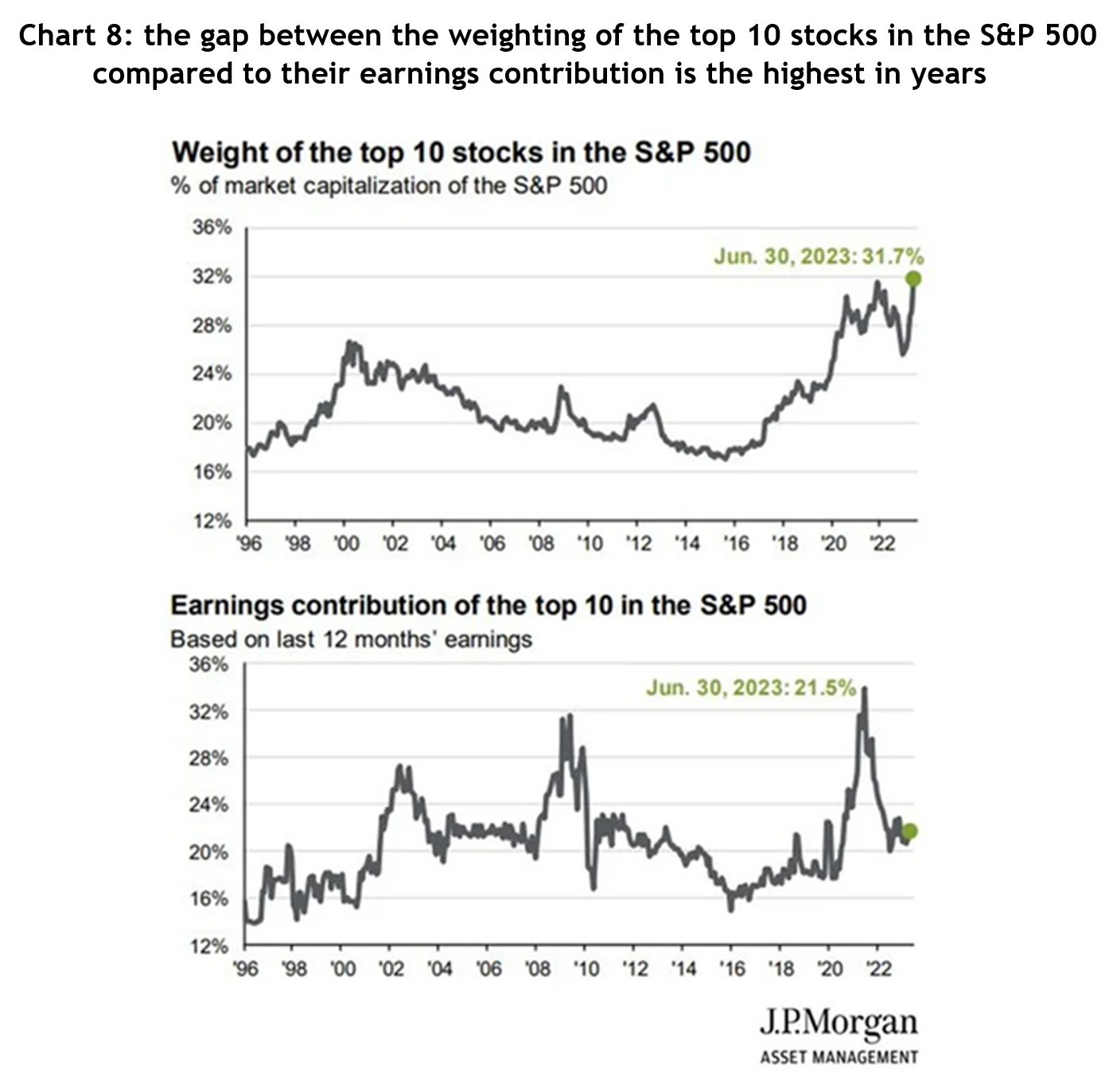

- The weighting of the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 at the end of June was the highest in more than 27 years at 32 per cent, but their contribution to earnings growth was the equal lowest in over 20 years at 22 per cent- see chart 8.

You only need to play around with Chat GPT to know that AI is very special and will be a game changer, and it is progressing astonishingly quickly. At the end of day, even if this AI-inspired rally really is a bubble, we know bubbles can last a lot longer and go a lot higher than anybody expects. Smart investors will know it’s worth having some exposure, but maybe just don’t bet the farm on it, yet.