Private credit is redefining fixed income

Private credit is redefining fixed income as an asset class, with returns as high as 10 per cent plus attracting an explosion of interest. But all that attention has drawn the usual cowboy operators, so smart investors need to be careful.

What is private credit?

Private credit is investing in loans made by non-bank lenders that can cover a broad range of purposes and borrowers.

Normally a private credit lender raises money from investors and doesn’t use debt, so zero gearing. That makes these companies very different to a normal bank, where the loan book will be dozens of times bigger than the bank’s equity.

Taking out a private credit loan is almost invariably much more expensive than borrowing from a commercial bank, with interest rates currently as high as 12 to 13 per cent. So why are borrowers flocking to private credit lenders?

Why the boom in private credit?

After the GFC, banking regulators around the world forced commercial banks to beef up their balance sheets, requiring them to back their loans with more equity to absorb potential losses, especially loans to sectors that had a history of high default rates, like commercial building and property development. That same regulatory crackdown caught up with the Australian banks in 2016, when their regulator, APRA, declared it wanted them to be the best capitalised banks in the world.

After that, it became far more profitable for Australian banks to lend for residential property, because they didn’t have to set aside as much equity on their balance sheets. Consequently, they all but abandoned some parts of the commercial lending market.

Spotting a huge, and growing, opportunity, private credit groups sprang up to fill the gap. Often staffed by the same experienced credit teams from the big banks who were now twiddling their thumbs, they got backing from investors with the prospect of outsized returns relative to the risk.

The result: EY estimates the Australian private credit market grew from $35 billion in 2016 to $109 billion by the end of 2022, a 21 per cent compounded annual growth rate. The global private credit market was estimated to have grown at 15 per cent per year between 2000 to 2022, reaching more than $1 trillion.

As often happens, Australia is a bit behind the US, where Foresight Analytics estimates non-bank lenders control about 50 per cent of the market for commercial real estate loans, and in Europe it’s about 25 per cent, while in Australia it’s around 10 per cent, but growing strongly.

What’s the attraction for investors?

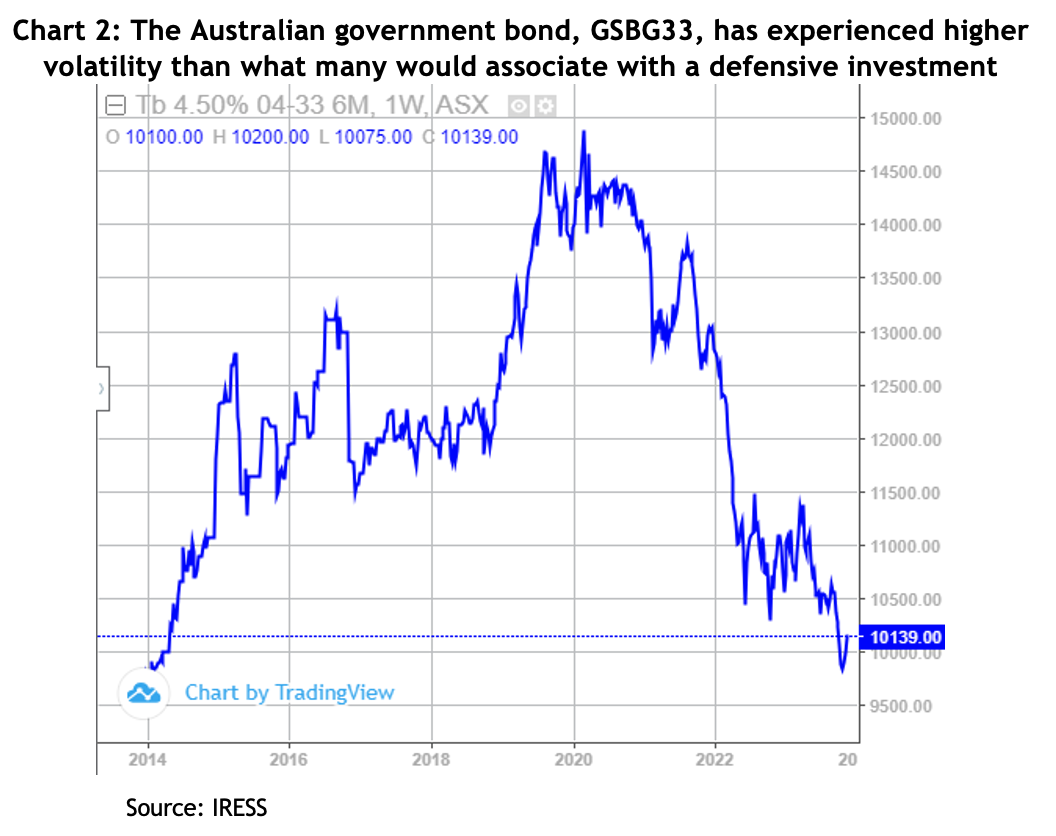

Fixed income plays two roles in a portfolio: first, to provide some income, and second, to have little, if any, correlation to growth assets like shares, in other words, be a defensive asset.

Income-wise, over 2023 there were a number of private credit funds that returned well above 10 per cent, even as high as 12 per cent. For context, the Australian 10-year bond yield peaked at 4.95 per cent.

In terms of low correlation to shares, the word “private” is the critical part. Unlike corporate or government bonds, private loans are not normally traded on public markets, which makes them far less volatile because there is no day-to-day repricing, the fancy name for which is “mark-to-market risk”. In 2022, when bonds and shares both fell heavily, well-managed private credit funds continued to pay their interest and the unit price never changed.

The other attraction is security. For example, a private credit fund that lends to property developers will take a mortgage over the project, including the land, just the same as when a bank lends to a homeowner. Usually, the lenders require a loan to valuation ratio between 60-65 per cent. That means if the deal goes pear-shaped and the private credit manager repossesses the property, it has a 35-40 per cent buffer before investors lose any money.

In addition, the lender will also normally take a charge over other company assets as well as get a directors’ guarantee, meaning their personal assets are on the line as well. Plus, Australian lending rules are tilted very much in favour of the lender, enabling them to impose onerous covenants on the borrower.

There’s a lot to like about investing in private credit, but its popularity has drawn a lot of new operators, not all of which are experienced in credit analysis and some of which are under pressure to get investors’ money to work so are not as fussy about who they lend to. On top of that, some private credit deals will tie up your capital for up to 18 months, or even “semi-liquid” funds will take 2-3 months to get your money back. It pays to do your homework carefully.