This article was written by our asset allocation consultant, Tim Farrelly. Inflation is a critical determinant of the direction of interest rates and bond yields, which in turn affects how pretty much every asset is valued. If inflation goes up, so do bond yields, which drives down asset values. So it follows that one of the reasons both bonds and equities have done well over the past seven years is because inflation has been low, but how long will that last?

By Tim Farrelly

What drives inflation?

In 1970, Milton Friedman had the answer…

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

– Milton Friedman 1970

But, by 1978, the answers didn’t seem quite so straightforward…

“Inflation is obviously a serious problem. What is the solution? I do not have all the answers. Nobody does. Perhaps there is no complete and adequate answer.”

– Jimmy Carter 1978

The historical record provides a lot of seemingly contradictory evidence as to what drives inflation. Soaring oil prices seemed to trigger the 1970s inflation episode but had little impact in the decade from 1998 to 2008 where the oil price increased by over 13 times and, yet, inflation averaged just 3% per annum.

Huge deficit spending was a key driver of the German hyperinflation in the early 1920s but seems to have had no impact on Japanese inflation over the past two decades.

More recently, Zimbabwean hyperinflation was associated with a rapid increase in the money supply but we have seen no impact on US or European inflation from the huge money supply growth over the past decade driven by Quantitative Easing.

At this point Jimmy Carter’s “It’s complicated” seems a better framework than that of Friedman. However, farrelly’s believes inflation is quite a bit simpler than Jimmy Carter believed. It would appear that there are three main causes of inflation that can act independently or in concert:

- Excessive wages growth;

- A shortage of goods and services; and/or

- Currency debasement.

Excessive wages growth

In most developed economies, wages are the key to inflation because they make up some 60% to 70% of the cost base of the economy. Excessive wages growth causes the costs of producing goods and services to rise, and businesses are forced to pass on those increases as higher prices or go out of business. Those higher prices drive a high rate of CPI inflation which employees then demand is factored into subsequent wage increases, which in turn drives cost and price increases – and so on. Welcome to the wage-price spiral.

Wages growth is not excessive where productivity growth matches or exceeds wages growth. Then we don’t get the pressure on costs or the need for price increases and so the wage-price spiral is broken. This relationship between wages and productivity was not lost on either party to the Accord between the Hawke Labor government and the Trade Union movement in the 1980s. Linking pay increases to productivity increases played a significant part in bringing Australian inflation under control in the 1990s.

Excessive wages growth can be a result of demand and supply imbalances. If an economy grows too fast, a shortage of labour can result in rising wages as businesses bid up the price of scarce workers. Typically, this is when central banks raise interest rates to take heat out of the economy and the imbalances are corrected over time.

Excessive wages growth can also come about where well organised unions create an artificial shortage of labour leading to wage increases and a wage-price spiral. This is particularly an issue in a closed economy, where offshore outsourcing is difficult. Opening up an economy to global competition significantly weakens employees’ ability to command out-sized wage increases.

A shortage of goods and services

When goods are in short supply, their price goes up. If the shortage is structural, as in a war-torn or otherwise failed economy, then the price rises are likely to be permanent and a wage/price spiral can set in.

In most developed markets, for most goods and services, this simply has not been an issue for decades. Commodities are an exception as they continue to be subject to large medium-term fluctuations in demand and supply. Prices do fluctuate wildly as a result but these imbalances tend to correct over time.

To illustrate the potential for commodity prices to influence inflation, students of the 1970s point to the twin OPEC oil shocks as the catalyst for a prolonged period of high, world-wide inflation. Between 1972 and 1980, oil prices rose from US$1.85 to over US$40 per barrel – an increase of 2100%.

Many wonder why the 1250% increase in oil prices between 1998 and 2008 had so little effect by comparison. The answer is because the 1970s increase was much larger and impacted a much larger part of the economy.

Firstly, the 13 times increase in oil prices from 1998 was from the very bottom of the market to the very top of the market, but neither the peak nor trough prices lasted for long. If instead we compare the 12-month average prices, we find an increase of seven times between 1998 and 2008 – still substantial, but a lot less than the 22 times oil price increase during the 1970s.

The second difference is that the world has become a lot more efficient in its energy use since the 1970s. It is estimated that it now takes 60% less energy to produce a unit of GDP than it did in the early 70s.

Put the two together and we have a much lower impact on costs and prices.

With energy at around 12% of the world’s cost base in 1968, a 22 times increase would cause the cost base to increase by a total of 280%, or 17% per annum, over eight years – but only if the world continued to use energy as it did before the oil shock, which of course it did not. We became much more efficient. So much so that, by 1998, the cost base of energy was closer to 5% of the economy and the seven-fold increase over the subsequent 10 years resulted in upward pressure on costs of around 35% or 3% per annum. Very different. That higher efficiency partly explains why the CPI didn’t increase by at least 17% per annum and 3% per annum following these oil price increases. In addition, businesses were not able to pass on all the cost increases and, in the 1970s at least, profitability plummeted. Finally, the 1998-2008 commodity boom was driven by the entry of China on the world stage and the opening up of markets worldwide. The price of many manufactured goods plummeted, offsetting the increased costs of energy related inputs.

Commodity prices can still cause medium-term spikes in costs but, in a world awash with capacity, resulting inflationary pressures tend to be muted and temporary.

Currency debasement

This has definitely been a factor in many inflationary episodes. Essentially, this occurs where there is a substantial increase in the amount of money in circulation without a corresponding increase in the supply of goods and services.

Normally, currency debasement is associated with deficit spending by governments on transfer payments – payments for which the government gets little or nothing in return. Transfer payments include things such as unemployment benefits, healthcare payments, unfunded pension payments and, arguably, military spending.

However, currency debasement is not just about government spending and is not just about paper money. The Spanish Price Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries occurred where gold and silver, the currency of the day, poured into the Spanish economy, predominantly from their New World conquests, Peru and Mexico. No new goods or services were produced and, as a result, the purchasing power of gold and silver fell substantially. The more gold that was plundered, the less it became worth.

When thinking about currency debasement, we need to be very careful about what we consider to be money. Most common definitions of money include cash in circulation, at call bank accounts and very short-term deposits. Unfortunately, these definitions can be very unhelpful when thinking about currency debasement.

When it comes to thinking about whether or not a currency is being debased, farrelly’s finds it useful to think about what is happening to balance sheets – and, in particular, what is happening to household net worth in nominal terms.

Take QE as an example. We all now know that QE has not been inflationary, but many are still confused as to why this has not been the case. Thinking about balance sheets really helps.

Consider an investor who owns $1 million worth of bonds and sells them to the Fed. The investor now has $1 million of cash and, in net terms, is no better off. The investor puts the cash on deposit with their bank who in turn gives it back to the Fed. The Fed now has an additional $1 million of assets, being its bonds and a matching liability, the $1 million it owes to the commercial bank. On day one, it too has no increase in net wealth. Finally, the commercial bank has an extra $1 million in assets, being its deposit with the Fed, and an additional $1 million of liabilities, the amount owed to the depositor. Again, on day one, the bank is no better off.

In nominal terms, no-one is any richer and so there is no debasement of the currency. In this case, government bonds should also be thought of as money – and narrow definitions of money that exclude bonds confuse rather than clarify the situation.

The role of floating exchange rates

Floating exchange rates have two major impacts on inflation. They can protect one economy from importing inflation from another country and, secondly, if large, exchange rate moves can impact costs and inflation in the home country.

In the days of fixed currencies, such as the 1970s, when one country experienced inflation, it exported it to its trading partners. In a floating exchange rate environment, when one country has high inflation, its currency falls in value with the result that its trading partners don’t feel the impact in terms of higher prices for their imported goods.

The recent Japanese experience illustrates both impacts. When Shinzo Abe was elected in Japan and promised higher inflation, the Yen fell by over 20% and importers of Japanese goods saw their prices fall by 20%. Even assuming that Abe is successful in getting inflation back to 2% per annum, it will take 10 years for importers to see their prices rise. For Japan, that rapid currency depreciation meant that the cost of imported goods rose substantially and, for a while at least, they did get a burst of inflation.

In this way, an exchange rate shock can generate an inflationary shock in the country experiencing that currency fall. Consider an economy for which imports make up 20% of GDP. A fall in the currency from $0.75 to $0.50 would have the impact of raising the cost of all those imports by 50%, for an overall increase in the nation’s cost base of 10%. This will almost certainly translate into an increase in prices, however perhaps not by the full 10%. Firstly, the impact often takes time. Importers often hedge their currency exposures and wear some of the increase by way of reduced profit margins. Further, there are substitution effects where local products takes the place of imports, or low cost substitutes are found for the same goods. Finally, manufacturers double their cost cutting efforts so as not to price themselves out of business. Nonetheless, there is a price impact and it can be significant.

The challenge is to ensure that the one-off shock does not become the catalyst for an ongoing wage-price spiral, which is where the central banks enter the picture.

The role of central banks

Most central banks today have an explicit inflation target – generally between 2% and 3% per annum. This is a relatively new phenomenon. Germany led the way in the 1970s when it successfully began using monetary policy to informally target inflation. In terms of adopting a formal inflation target, New Zealand led the world when, in 1989, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand became the first central bank in the world to adopt an explicit inflation target. The RBA followed suit in 1993.

One of the strengths of the inflation targeting approach is that it helps ward off the onset of a wage-price spiral following a one-off shock to prices such as a rapid currency depreciation or an external commodities price shock.

To date, central banks around the world have been extremely effective in using formal inflation targeting to bring inflation under control – some would argue too effective, but that is a discussion for another time.

When it all goes wrong – the Weimar Republic, 1919 – 1923

Excessive inflation is rarely a result of just one thing going wrong – like a plane crash, there needs to be a series of errors. To get to hyper-inflation, everything has to go wrong.

Germany in the early 1920s just about collected the full set. A combination of strong labour unions, large deficit spending, a complacent Central Bank and external shocks in the form of major currency devaluations all created a wage-price spiral financed by ever faster printing of money. The end result was that inflation went from 37% per annum in 1920, to 3000% per annum in 1922, to a total collapse of the currency and economy in 1923. But we are a long way from any of that today.

Where are we today?

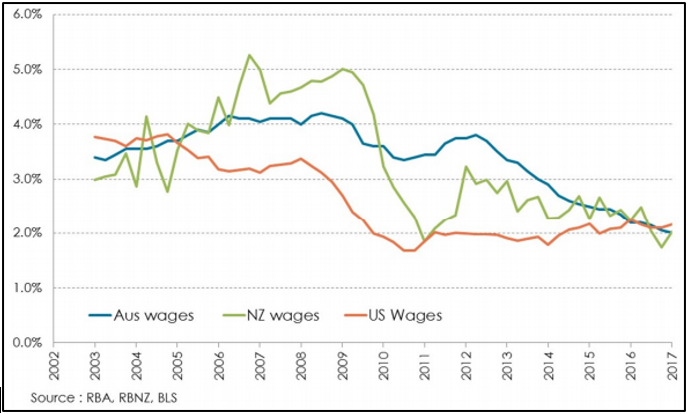

Australian investors should be mainly interested in Australian inflation and NZ investors in NZ inflation. Domestic inflation will drive domestic interest rates and domestic real returns. It is also useful to keep an eye on the US, as monetary policy there clearly impacts markets worldwide.

Going forward, the inflation outlook in Australia, New Zealand and the US is relatively straightforward. We have minimal currency debasement and the prices of manufactured goods are generally continuing to fall as globalisation and technology drive down costs.

From today’s standpoint, wage inflation is the key to inflation – and it is falling. Figure 1 shows average two-year wage inflation in Australia, New Zealand and the US. We use the two-year change to take out some of the noise in the data and to show this very clear picture – wages growth is at historically very low levels in Australia and New Zealand and, in fact, in most of the developed world.

Figure 1 : Wages growth %pa (two-year average)