Are Australian shares expensive?

There’s something innately comfortable about investing in companies you know and a market you’re familiar with, so it’s hardly surprising Australian investors, like their peers all over the world, have a bias to investing in their home market.

And Australia has some great world class companies, like the mining giants BHP and RIO, CSL, Cochlear, Goodman Group and James Hardie, to name a few. Plus, there’s a host of terrific domestically focussed companies that are household names too, like JB Hi-Fi, Commonwealth Bank and Woolworths.

Throw in the benefits of Australia’s famously high dividends and the bonus of imputation credits, and it’s little wonder Australian investors will typically have a weighting to ASX listed companies way in excess of the 2.5% they account for in total global share markets.

But it does pay to keep a careful eye on whether Australian shares represent good value compared to investing into international shares.

Over the long run, share markets tend to follow the growth in company earnings, but in the short run, sentiment can be extremely influential. Changes in sentiment are captured in the price to earnings (PE) ratio.

If earnings for the overall share market grow by 10 per cent in a year, and the market has risen by 10 per cent, then the PE won’t have changed (ignoring dividends for the moment). That means sentiment hasn’t played any part in the returns enjoyed by investors.

However, if earnings growth was 10 per cent and the market went up by 20 per cent, then the PE ratio has doubled, meaning sentiment has played a big role in returns.

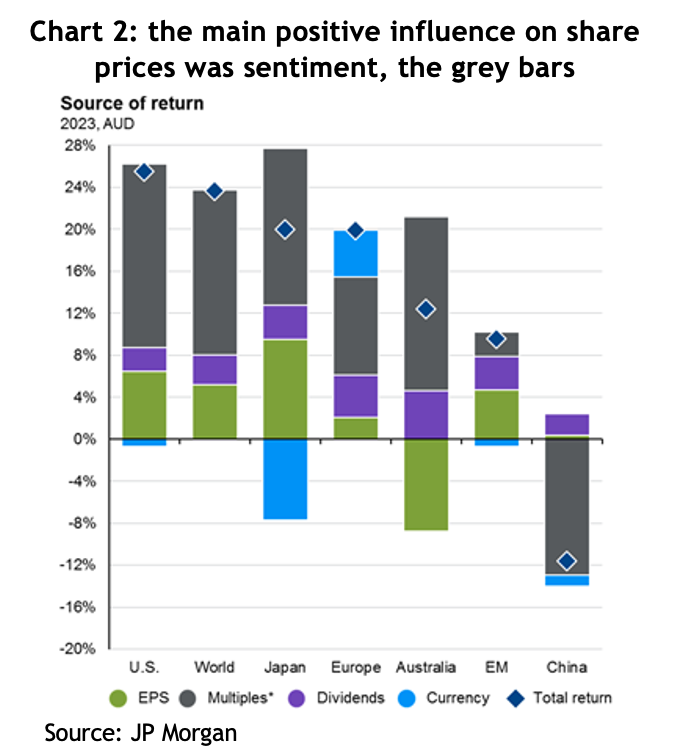

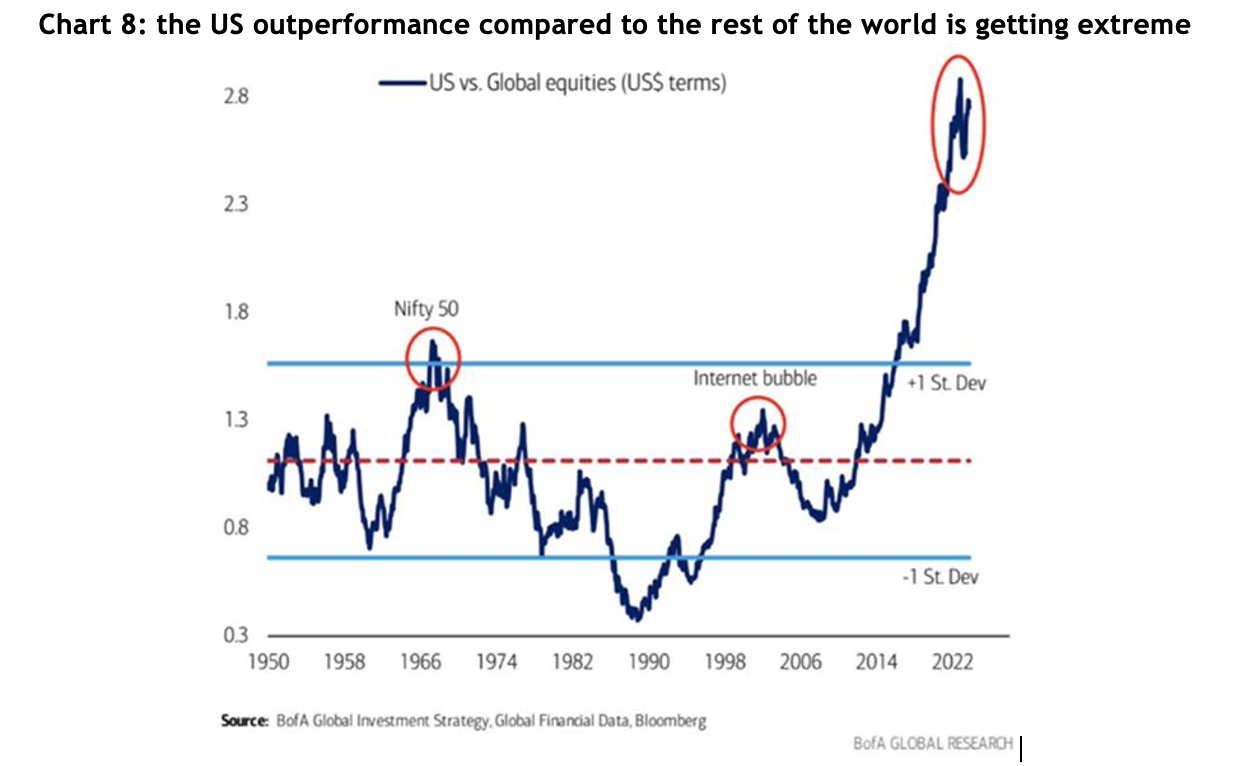

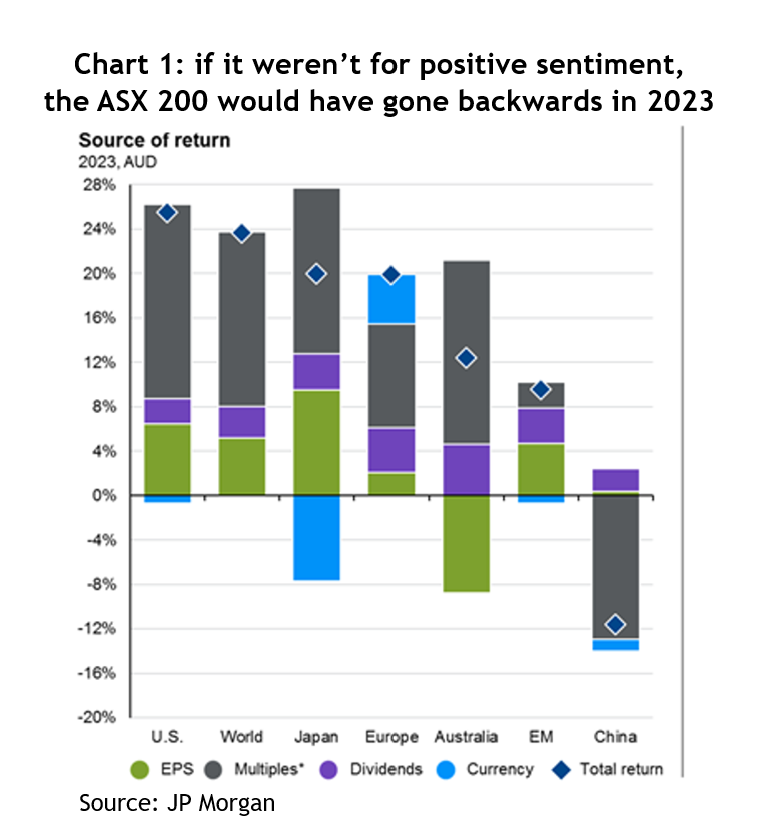

In 2023, PE ratios went up strongly across the world, in part bouncing back from being whacked in 2022. But for Australia, it was particularly important. Of the 12 per cent return from the ASX 200, a positive change in sentiment contributed about 16 per cent and dividends about 4 per cent. That means earnings growth was minus 8 per cent; not real flash when you compare it to the US’s 6 per cent, Japan’s 9 per cent, and even Europe managed 2 per cent – see chart 1.

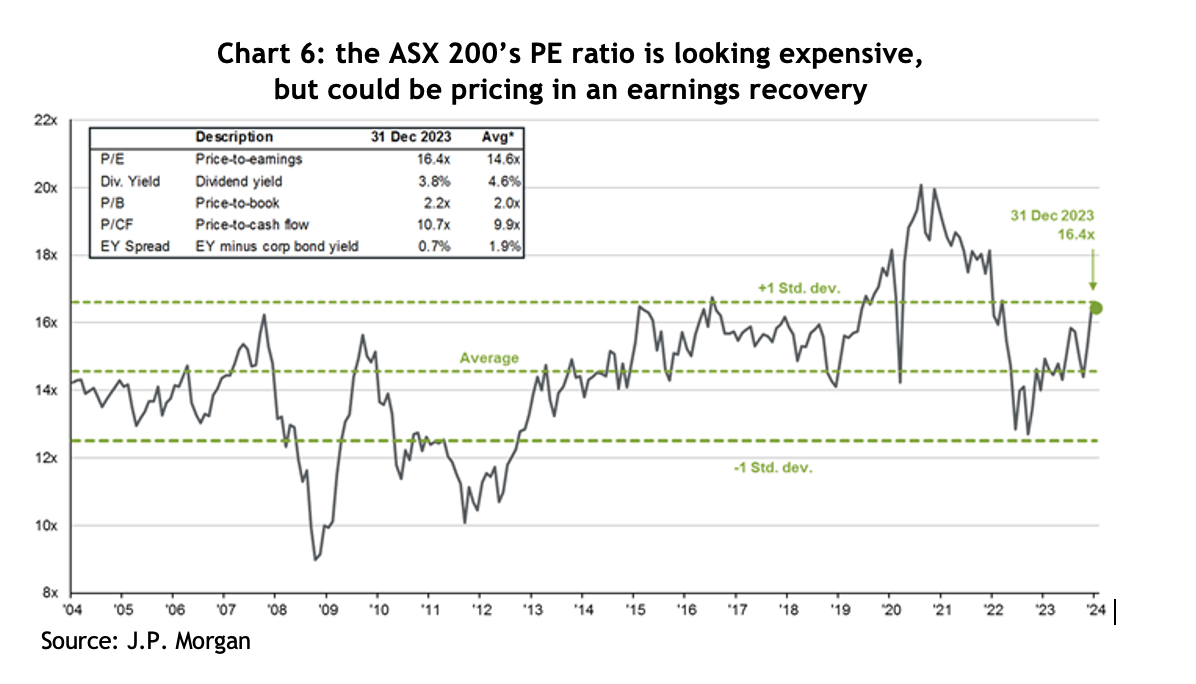

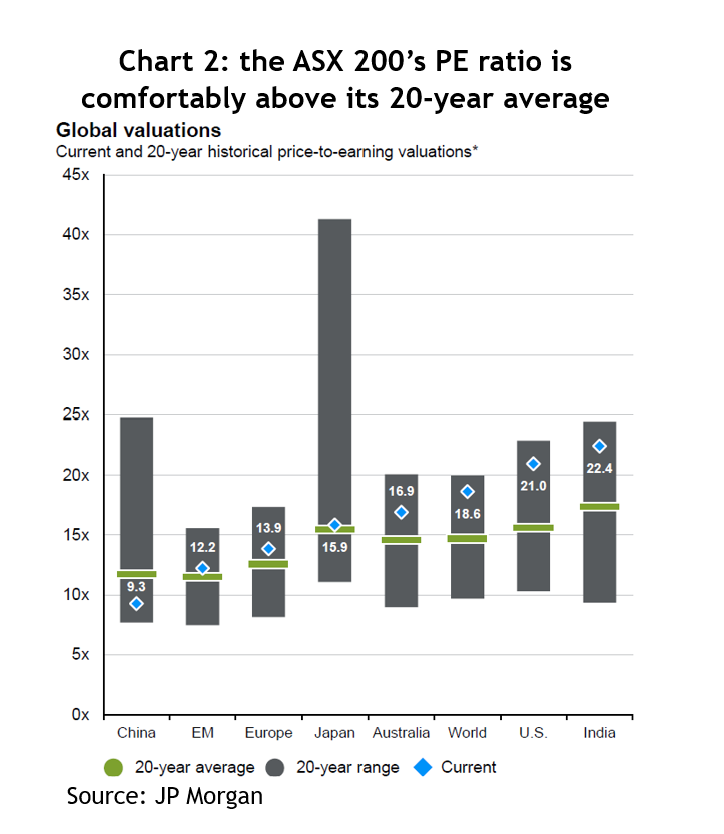

At the end of March this year, the ASX 200 was trading on 16.9 times forecast earnings, which makes it pretty pricey compared to its 20-year average of 14.9 – see chart 2. But that optimistic outlook isn’t matched by what analysts are forecasting earnings growth will be, which for the calendar year of 2024 is barely above zero and for 2025 is about 2 per cent.

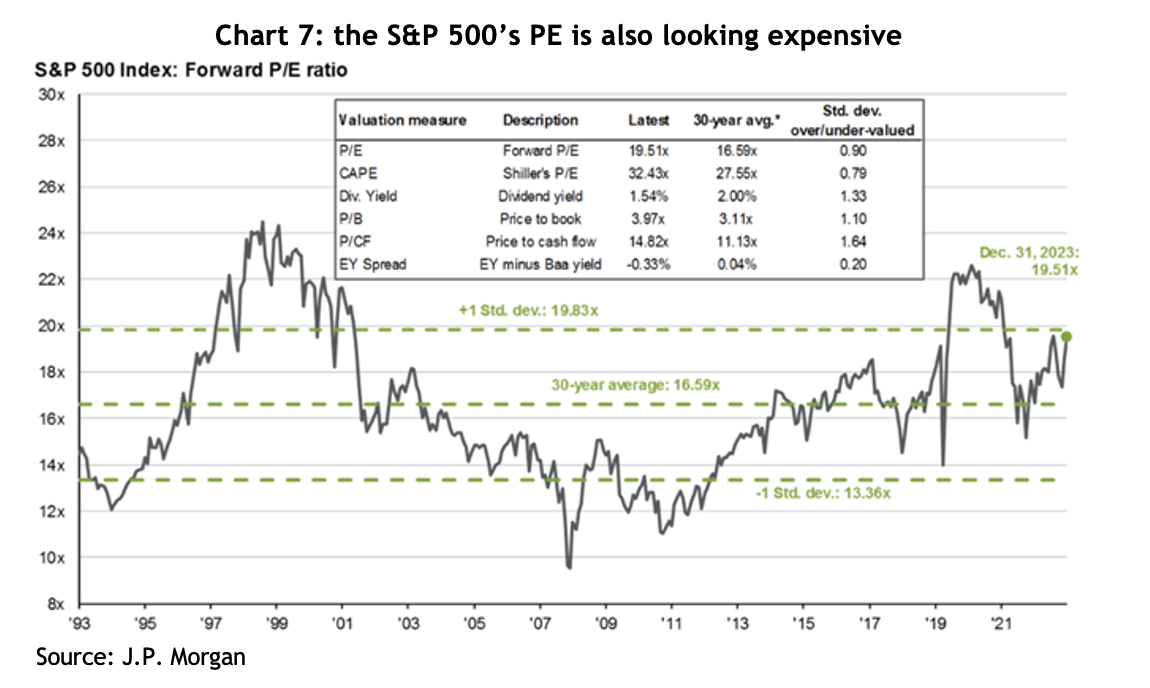

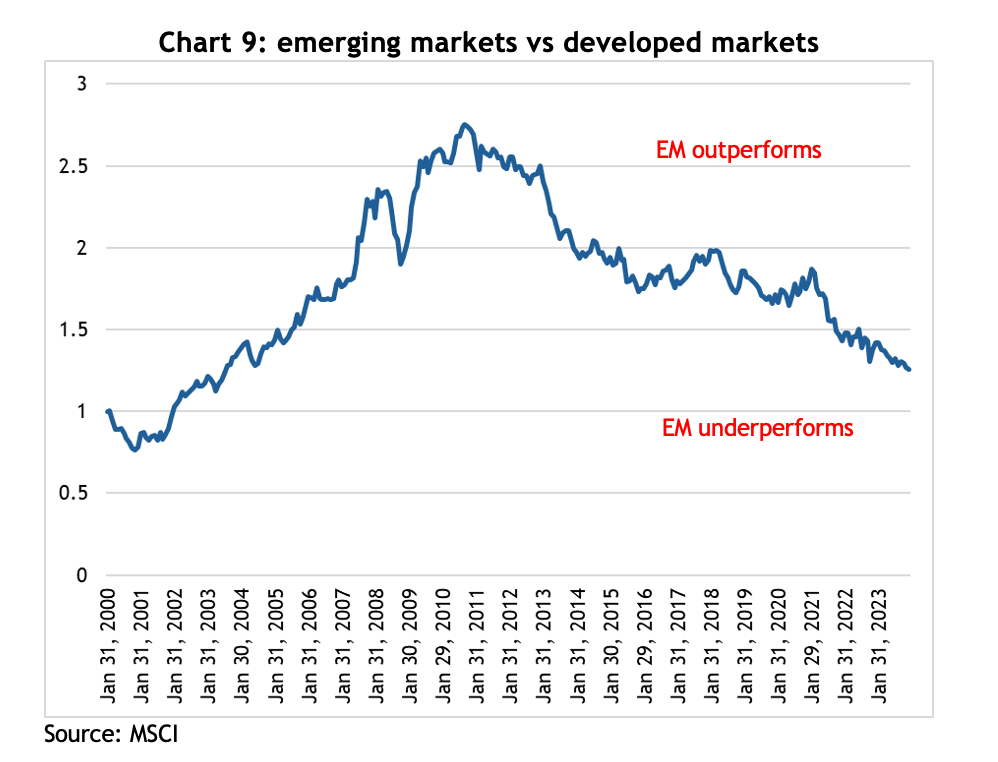

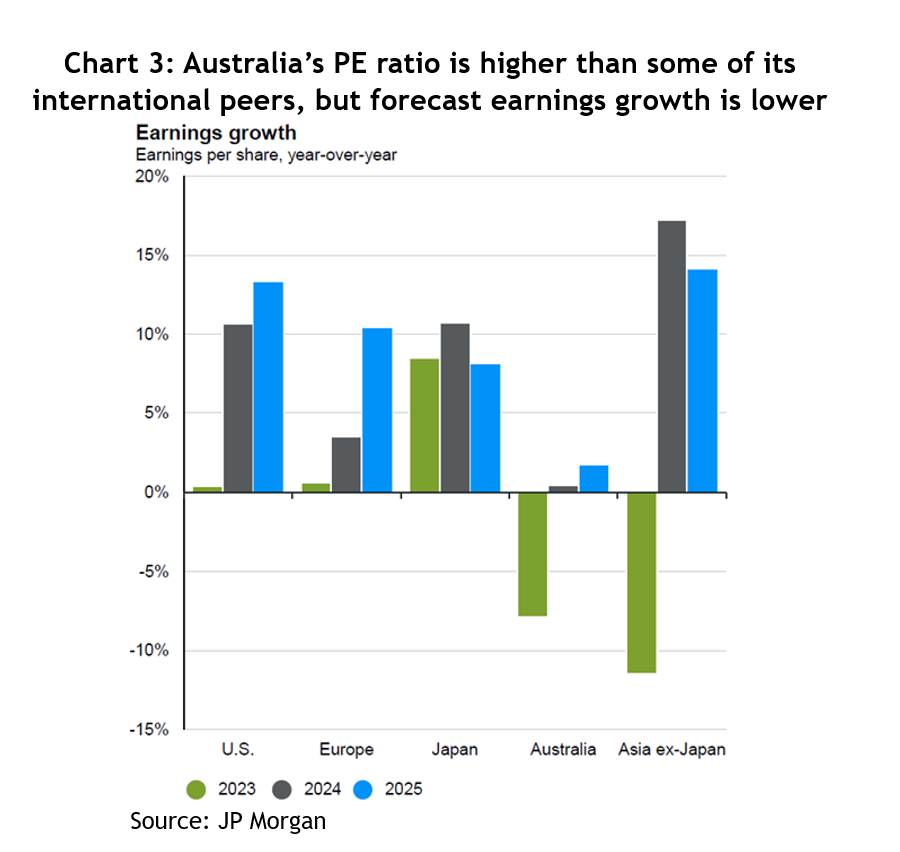

Meanwhile, other international markets have much more favourable metrics. While the US is trading on a higher PE of 21x, its forecast earnings growth for 2024 is 11 per cent and for 2025 it’s 13 per cent. Europe is trading on 13.9x, with earnings growth forecasts of 3 per cent and 10 per cent. For Japan, it’s 15.9x, 11 per cent and 8 per cent – see chart 3.

Even if you add the 1.4% average extra return from imputation credits, it still leaves Australia looking expensive compared to other international markets.

How much to allocate to international markets and how to do it are the obvious questions. The amount, or weighting, depends on a bunch of different considerations, like how any change would be funded. Does it mean selling holdings that would crystallize a capital gain? Do you have an income target for the portfolio? If yes, how much comes from fixed income versus dividends? If you have to make regular withdrawals from the portfolio, such as a pension, would you be comfortable funding that through a combination of income and harvesting capital gains?

As for the how, there’s an enormous range of exchange traded funds (ETFs) available on the ASX that enable a smart investor to lift their international allocation. If you’re happy just to follow an index, Vanguard gives you a one-stop solution with its Global Shares ETF (VGS), or you can get US exposure to the S&P 500 or NASDAQ.

Alternatively, there are ETFs that use an algorithm to work out what holdings it will buy. A very popular one is VanEck’s International Quality ETF (QUAL), which holds 300 of the world’s highest quality companies and includes the likes of Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Nike, Johnson & Johnson and Unilever.

There’s no shortage of ways to help break free from the home country bias, it just takes a bit of digging, or, if you don’t feel confident to do that, ask an adviser.