Bubble Trouble Brewing

This article by Jason Todd, a strategist at Macquarie Wealth, takes a measured look at whether the Australian share market is overvalued, and whether the tech sector is in a bubble.

The bulls versus the bears

When equity markets began to rise back in late March, we had no problem thinking that liquidity would do the ‘heavy lifting’ as long as COVID-19 cases were not still rising and economic expectations were not still falling. It was right to take this stance. Now the equation seems much harder to solve. COVID-19 cases are rising again but markets do not seem particularly concerned even though valuations have expanded by an extraordinary amount. There appears to be two schools of thought emerging to explain the current backdrop.

The first, suggests that markets are becoming irrational and are in the midst of a liquidity-fuelled rally that is fast taking on bubble-like characteristics. This view argues that investors are being driven by the fear of missing out (FOMO), paying an unjustified scarcity premium for earnings growth and that momentum rather than fundamentals matter.

The alternative view is that markets are pricing in a combination of record low bond yields, an unwavering commitment by policy makers to keep economies and the financial system afloat and the willingness to pay a premium for structural growth. This is pushing valuations higher in areas where COVID-19 has accelerated change such as technology while pushing valuations lower in areas under downward pressure such as traditional retail and property.

It is hard to say which view will ultimately prevail as we think there are elements of truth to both sides. The risk-reward for certain pockets of the market are becoming hard to justify, but in general, we do not see broad signs of “bubble trouble” across equities. Traditional warnings signs such as speculation activity are not broadly evident even if tech valuations are looking troublesome.

Are equities in a bubble?

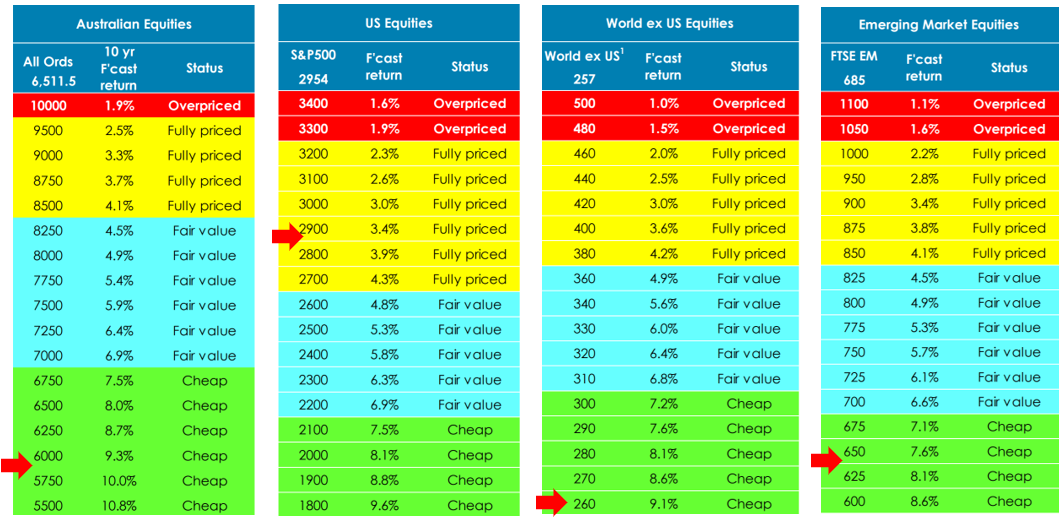

A ‘bubble’ is defined as a rapid rise in the price of an asset that is not supported by fundamentals. A typical sign of a bubble is a sharp increase in valuations to extreme levels. For the Australian market, valuations are high but outside of a reversion in the drivers supporting risk assets in general, we don’t think they have reached a self-correcting level.

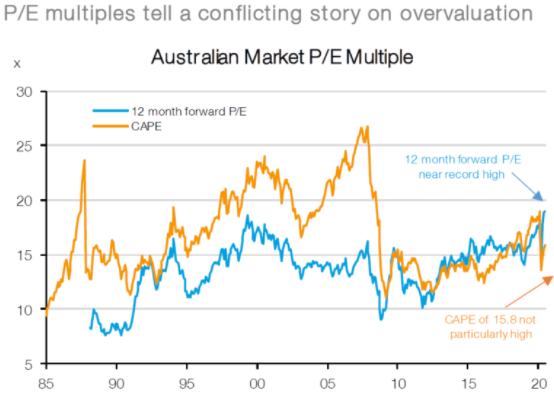

The 12-month forward P/E multiple for the Australian market has risen sharply since 23rd March and now sits at a near-record high of 19.1x. However, the P/E multiple has been boosted by the COVID-19 induced collapse in earnings which we think is not a permanent hit. In addition, the CAPE is only 15.9x. This is well below previous peaks and is below its long run average of 16.6x. So far so good…right?

Source: Factset, IRESS, MWM Research, July 2020

Is there bubble trouble in pockets of the market?

We do not think Australian equity valuations are anywhere near bubble territory and nor do we think other traditional indicators of bubble-like behaviour are evident. However, we cannot say the same for Australian technology stocks which are now trading on an eye watering 60x forward earnings!

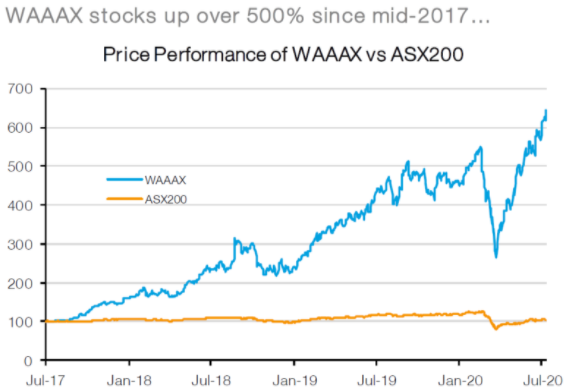

These valuation metrics look even more concerning when only the WAAAX stocks are considered (Wisetech, Afterpay, Appen, Altium and Xero). These 5 stocks have seen prices rise more than 500% over the past 3 years versus the broader ASX200 index which has barely risen above 0% over the same period. This has pushed 12-month forward P/E valuations for WAAAX to a new all-time high of 168x versus a paltry 19x for the ASX200.

Source: Factset, IRESS, MWM Research, July 2020

Part of the extraordinary price appreciation and valuation re-rating has been due to a much stronger and less cyclical earnings outlook, but it has also been fuelled by record low interest rates which disproportionately benefit high multiple/long earnings duration stocks. In fact, the WAAAX stocks have seen earnings grow 2.5x over the last 3 years – an impressive outcome versus the broader market which has seen earnings decline. However, this has been dwarfed by the near 6-fold increase in share prices over the same period!

Source: Factset, IRESS, MWM Research, July 2020

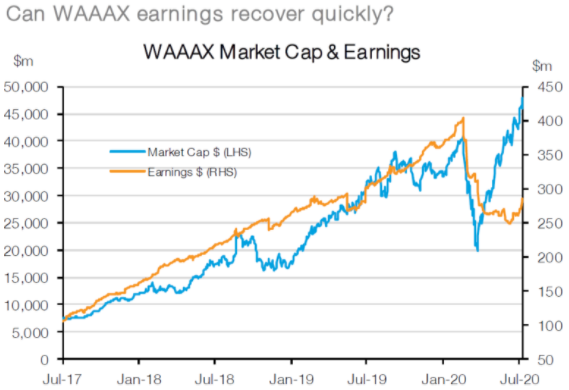

To put this in context, the WAAAX stocks have seen earnings increase by A$181m and their market cap expand by a staggering A$41bn. Back in 2017 investors were willing to pay 71 for each $1 of earnings and now these same stocks are commanding 168 for each $1 in earnings. In other words, investors have been willing to ‘pay up’ for the superior earnings performance of WAAAX stocks but at an increasingly higher and higher rate.

Is there a global growth stock bubble?

The re-rating of growth stocks is not unique to Australia. The WAAAX ‘bubble’ is part of a larger issue relating to the willingness of investors to bid up stocks which have a strong, structural, and/or transparent earnings growth outlook. ‘Growth’ stocks (of which WAAAX is a component) have been fiercely bid up as one of the few sources of structural earnings growth in the Australian market.

In other words, in a world where earnings growth is scarce, any earnings growth has become more valuable. This has also been seen in the recent performance of the FAANG’s (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Alphabet – formerly Google). This collection of stocks has also seen valuations ratios explode in recent years with momentum rising even faster in recent months because of an acceleration in their earnings outlook thanks to COVID-19.

Source: Factset, IRESS, MWM Research, July 2020

The other big factor, ultra-low interest rates, has also played a part. All other things equal, a lower discount rate would not only increase the fair value P/E multiple of the market generally but would also increase the dispersion between high and low P/E stocks. However, the current unprecedentedly high P/E dispersion exceeds the extremes seen during the Tech bubble of late 1999/early 2000, which suggests caution may be merited.

What’s the right price for “scarcity” value?

In a world where earnings growth is scare, what is the right price for the rarest of structural earnings stocks like technology, which the market is assuming can access that growth? Is it 50x future earnings, 100x future earnings, an eye watering 168x future earnings or something even higher? Only time will give us the right answer, but we think it is worthwhile trying to determine what conditions would need to prevail in order for these stocks to maintain these multiples (or the alternative – what would need to change for these stocks to suddenly lose their scarcity premium?). Gavekal’s Louis Gave believes there are 4 factors that would drive this reassessment:

- An improvement in the macroeconomic growth outlook and higher interest rates.

- Markets stop seeing technology companies as having scarcity value (i.e. government regulation).

- Another scarce asset becomes popular (i.e. gold? Bitcoin?); and

- Technology stocks disappoint.

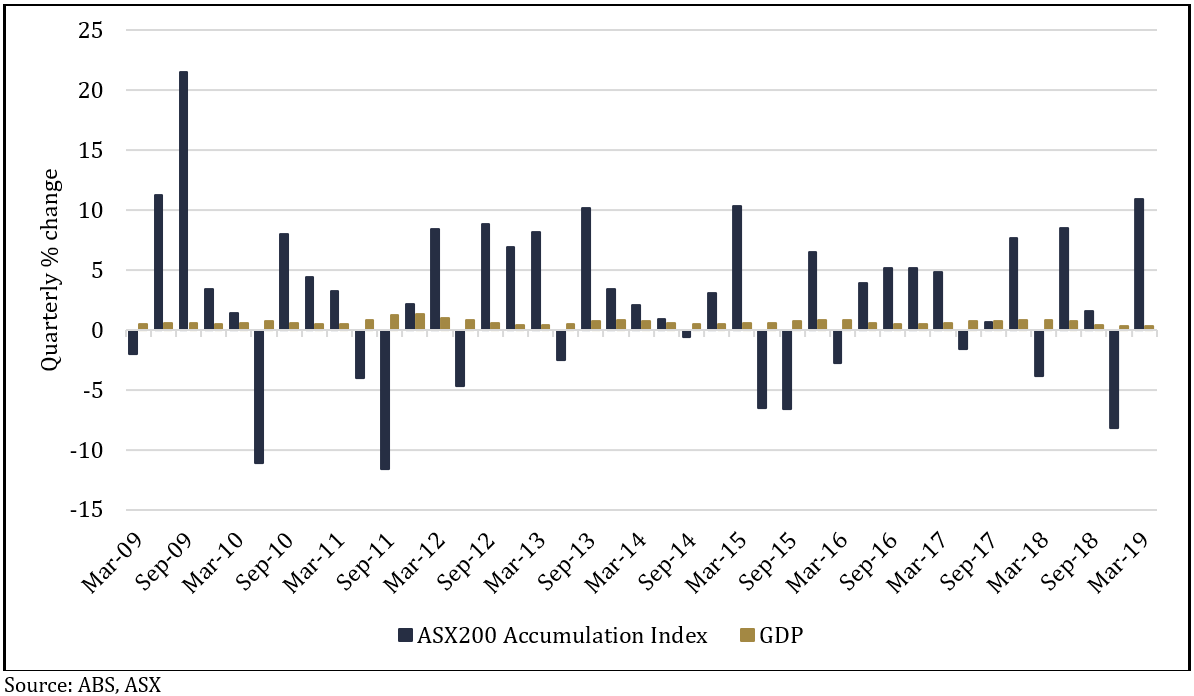

We think equity markets are optimistically priced and waiting for economic fundamentals to catch up, but they are not at an extreme (bonds are even more expensive). Similarly, retail sentiment is bullish but not exuberant, cash levels have come off their highs, but remain exceptionally elevated and capital raisings are still being gobbled up (predominately by institutional and not retail money). On the other hand, there have been some anecdotal signs of rising market ‘madness’ in the US with investors fiercely bidding up bankrupt companies, retail account openings have exploded (in part because many have been stuck at home) and some daily price moves have been extreme.

The technology sector is another kettle of fish. In the US, valuations are high but nothing in comparison to our own WAAAX stocks. On the other hand, there are still few signs of speculative activity stretching more broadly into financial assets and the scale of global (and domestic) liquidity injections is nothing we have seen before. We are not saying that fundamentals don’t matter because in the end they always do, but it is quite possible that the combination of easy money and a slightly better cyclical outlook push multiples for both technology and the broader market even higher!

Over the coming 12 months, we think investors should maintain a pro-growth portfolio allocation (overweight equities versus bonds and cash) and be prepared to look through any near-term fluctuations or use weakness to reallocate back into the equity market. Despite near-term risks, we think the downside risks are more likely to slow the recovery rather than put the cyclical recovery at threat. This could lead to a more drawn out rebound, but if economic growth and corporate earnings continue a path back to trend, then, in combination with record low interest rates, this will be sufficient to propel markets higher. In addition, while valuations for equity markets are not overly appealing, they are even worse for the bond market with yields not far from their lower bound and as a result bonds continue to give away a substantial yield premium to equities.