iversification has been called the last free lunch in investing. By spreading your exposure you reduce your risk – if one part of your portfolio is zigging hopefully another part will be zagging. But there’s a lot more to a diversified portfolio than just buying bank shares as well as resources.

We met with a new client recently who was confident his portfolio was diversified because he had a sizeable chunk invested in the big four Australian banks for good dividends, as well as the big resources companies if there was a growth cycle that lifts commodities prices, plus there were various other holdings. He also described himself as a conservative investor, because he didn’t trade very much.

In fact, his portfolio was far from conservative because he had very high concentration risk. For a start all his eggs were in the Australian equities basket. There is a natural bias to invest in your local share market, because it’s full of companies you’re familiar with, from supermarkets, to banks, to retailers and, hey, the Australian economy’s done super well not having experienced a recession for a record 25 years.

But there are several risks in this strategy. First, familiarity with a brand doesn’t mean you know how the underlying business is going. On the face of it a few years ago Woolworths seemed to be doing fine with the share price at an all time high, yet it dropped 45% over the next couple of years. Similarly with Telstra, whose brand has been ranked as the most valuable in Australia, has almost halved over the past couple of years.

Secondly, the Australian share market is not a good reflection of the domestic economy. The finance sector accounts for 35% of the share market but only around 10% of the economy. Likewise, resources are 18% of the ASX 200 but even at its peak in 2010 was only 8% of the economy.

Probably the most obvious argument to not be entirely invested in Australian equities is that the ASX 200 is about 2% of global market capitalisation and what drives our market can be entirely different to what drives overseas markets. For example, information technology companies make up 24% of the US’s S&P 500 index and have more than tripled over the past five years, whereas IT is 2% of the Australian market.

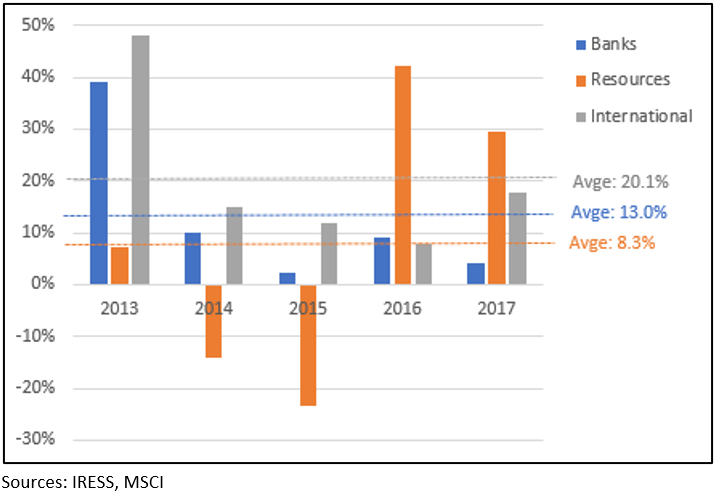

Chart 1 compares the performance of the big four Australian banks (including dividends and franking), the big two resources companies (ditto) and the MSCI All Country Index ex-Australia over the past five years, and shows how different sectors and markets can give very different returns over the same period. In fact, you can see the average return from the international markets was 2.5 times the resources and 50% more than the banks.

Chart 1: Australian banks and resources returns over 5 years vs MSCI All Countries ex-Australia

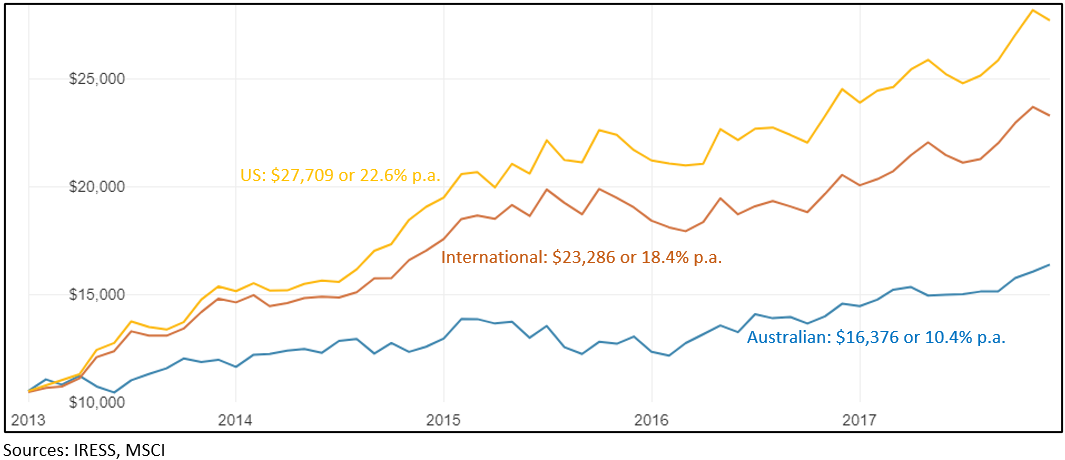

Chart 2 is another way of looking at the same thing and shows the returns you would have seen from investing $10,000 in Australian shares, compared with US and international shares, over the past five years to the end of 2017.

If you’re a brilliant stock picker then you should be able to do well whatever market you’re investing in, just look at Warren Buffett’s record. The unfortunate truth though is the 87-year-old Sage of Omaha has obsessed about investing since he was 10 years old. Realistically there are very few of us who are anywhere near good enough to make a living off share investing, let alone become a billionaire.

If you’re prepared to admit your fallibility, then the safest way to build in both protection and performance to a portfolio is through genuine diversification, across asset classes and geographies.