It’s getting hard to find someone who isn’t despairing of politicians, of all stripes, who can’t seem to see past the next election cycle. Time after time self-interest and holding on to power take priority over long-term planning, and it’s not just in Australia. But there is at least one country that stands out as an example of politicians playing the long game in doing the right thing by their country and future generations.

Norway has long been blessed with politicians that think ahead. As long ago as the 1960s there was active debate that introducing a national insurance scheme without securing its future funding would unfairly burden future generations. So, with the best of intentions, in 1967 the government established the Government Pension Fund. It was a flop: the fund was restricted to investing in bonds and the government was allowed to raid it to help fund programs such as public housing and regional industrial development. By the late 1970s there was very little new capital being invested into the fund, and even today, it is only worth about US$30 billion.

However, Norway has also been blessed with an enormous endowment of oil, so it’s currently Europe’s biggest petroleum producer and the world’s seventh largest oil exporter, accounting for about 25% of the country’s GDP.

By the early-1980s Norway had been enjoying well over 10 years of strong oil revenues when the government came to two important realisations: one, if they kept spending all the oil revenues as they came in they would fall victim to the so-called ‘Dutch disease’, where one sector of the economy grows so strongly that it sucks the oxygen out of other sectors; and two, spending all the revenue today means future generations are deprived of the benefits of this one-time resource endowment.

In 1983 a committee proposed the creation of a fund that would look after the oil revenues, but even Norway isn’t immune to the political process. It took until 1990 for the government to pass a law establishing the Government Petroleum Fund (now called the Government Pension Fund Global), then it took another six years of working out the rules before the fund was seeded.

Critically, the pollies managed to agree that every kroner of the government’s oil licensing and tax revenues (by the way, oil companies pay 78% tax on net profits: 27% company tax and 51% resource extraction tax, and they’re still lining up to play) would be channelled into the fund and the parliament’s fiscal rules allow the government to spend the fund’s inflation adjusted return each year, which is expected to be about 4%, but they can’t touch the principal. Also, because they wanted to avoid juicing the domestic economy, the fund is only allowed to invest internationally.

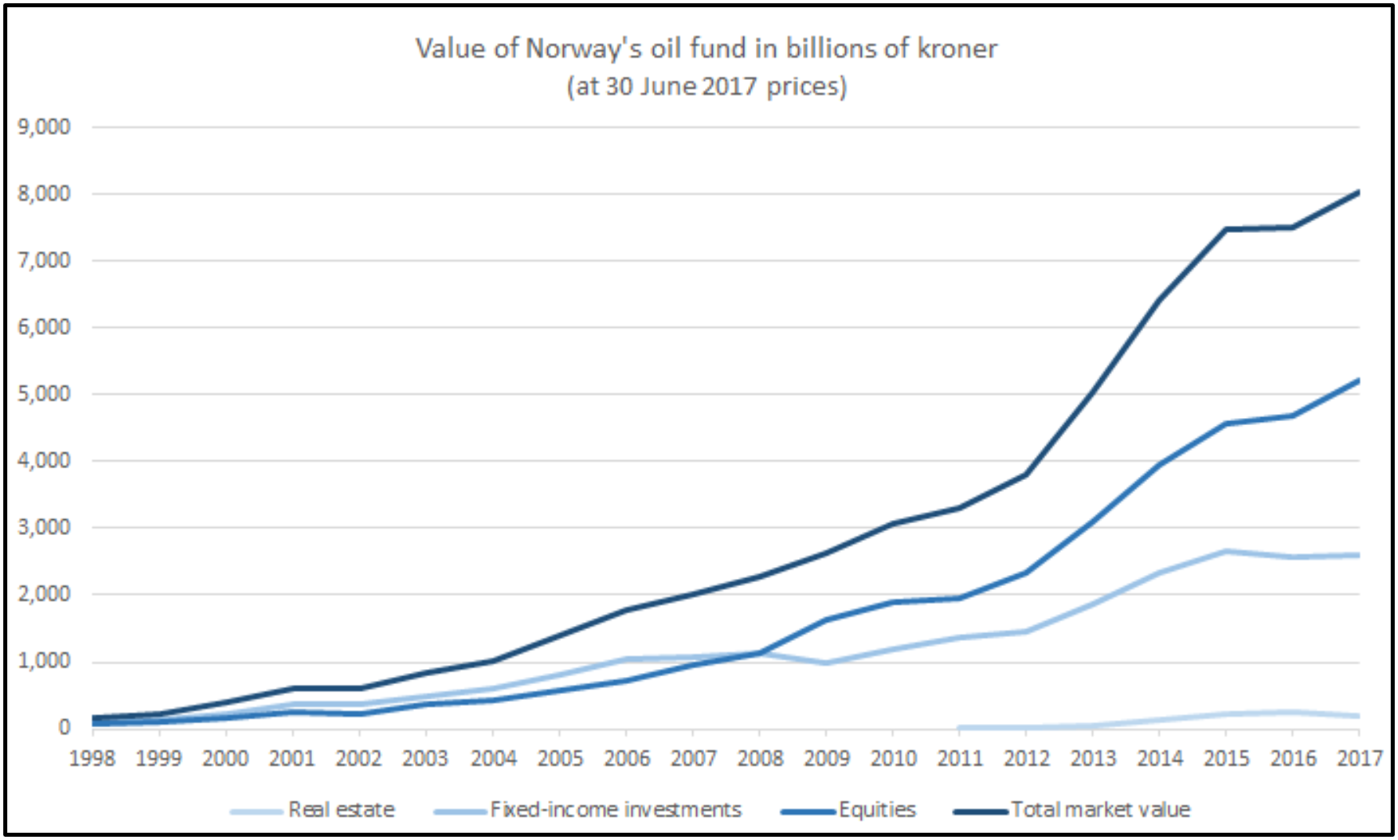

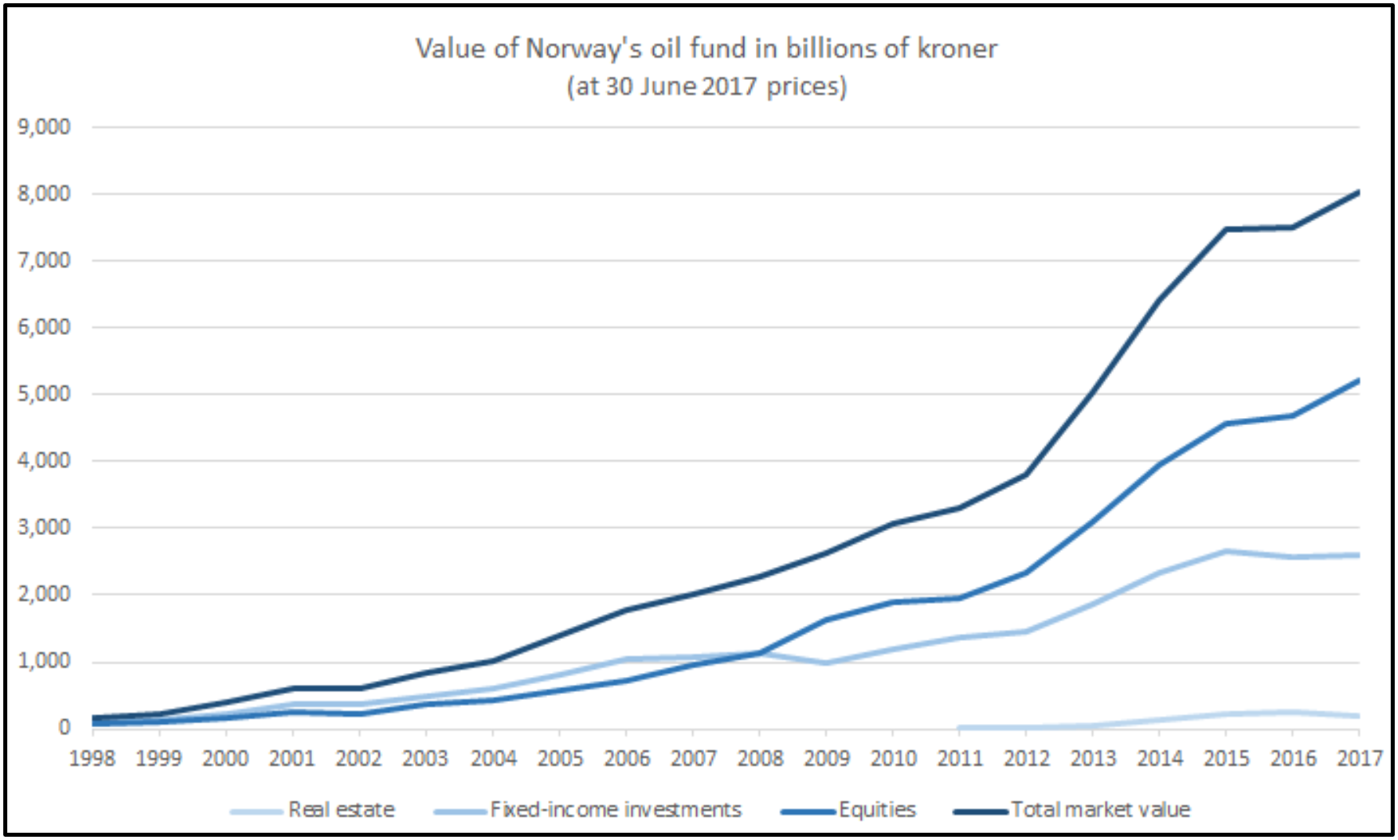

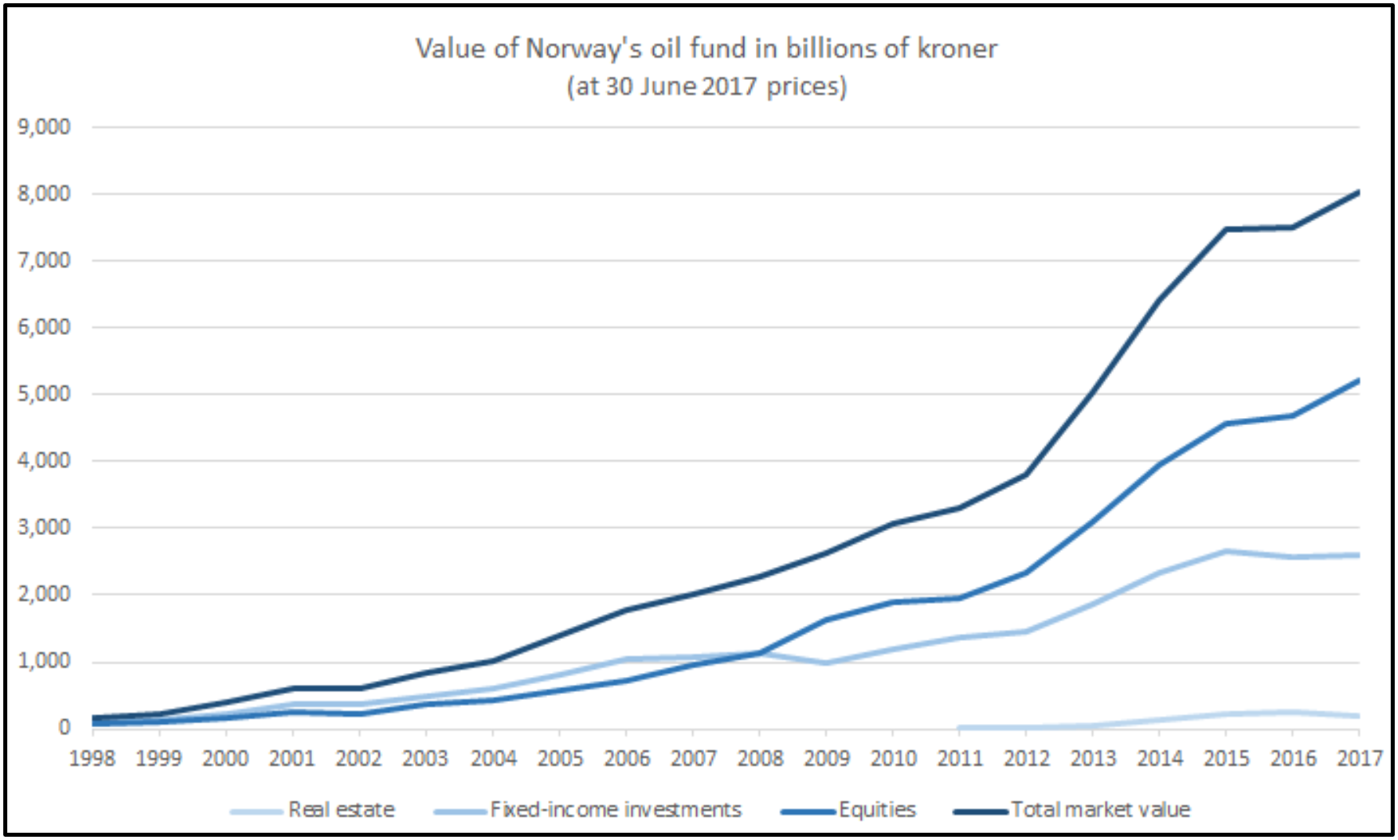

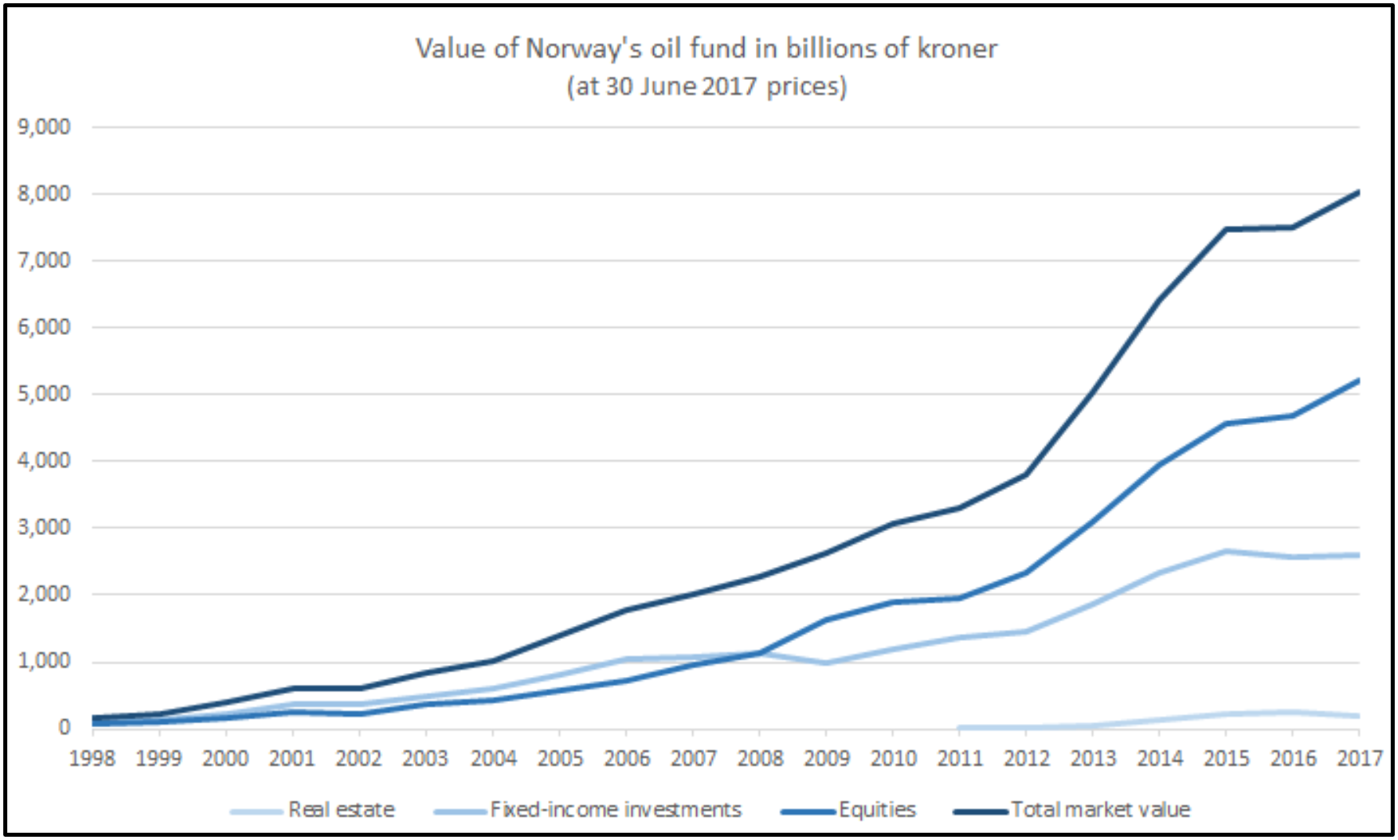

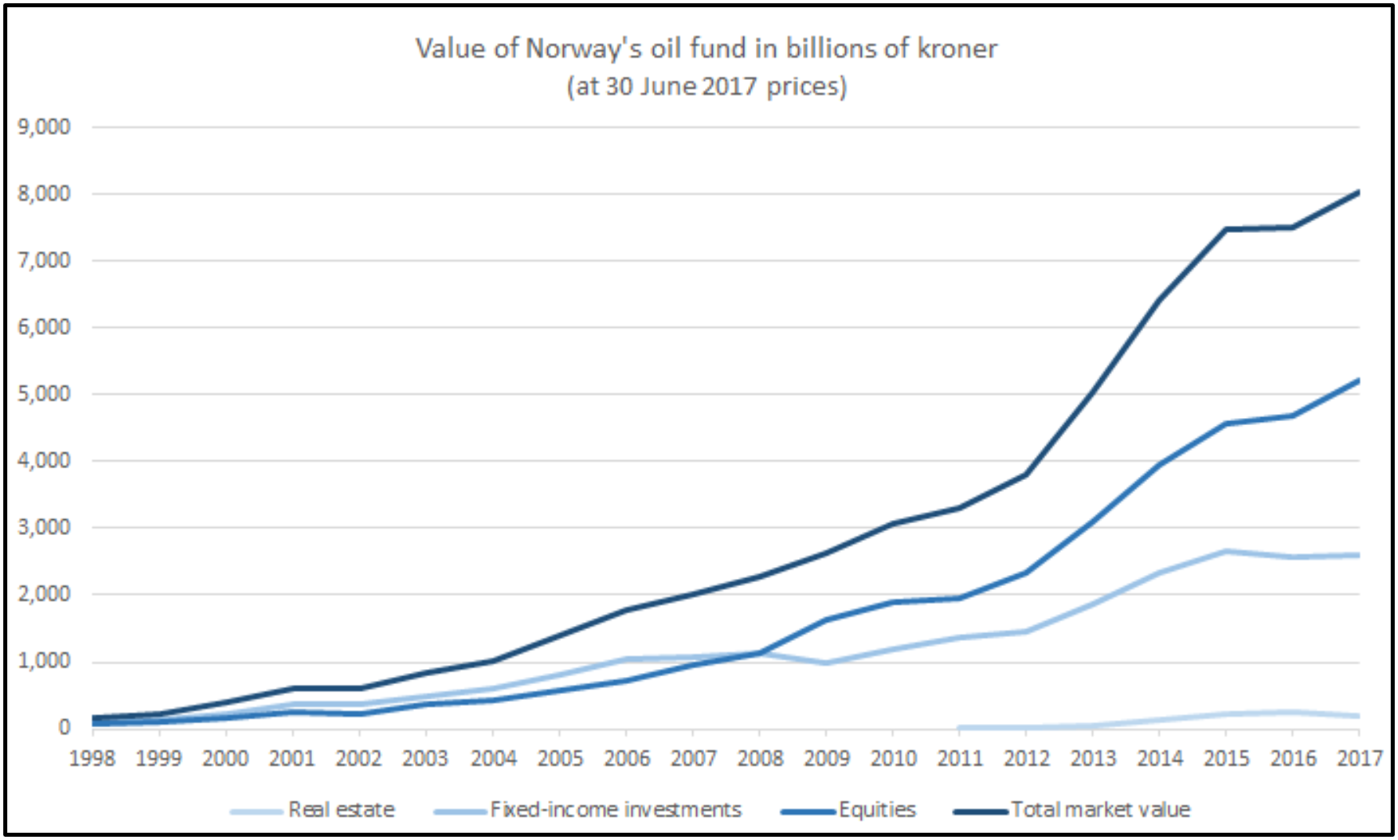

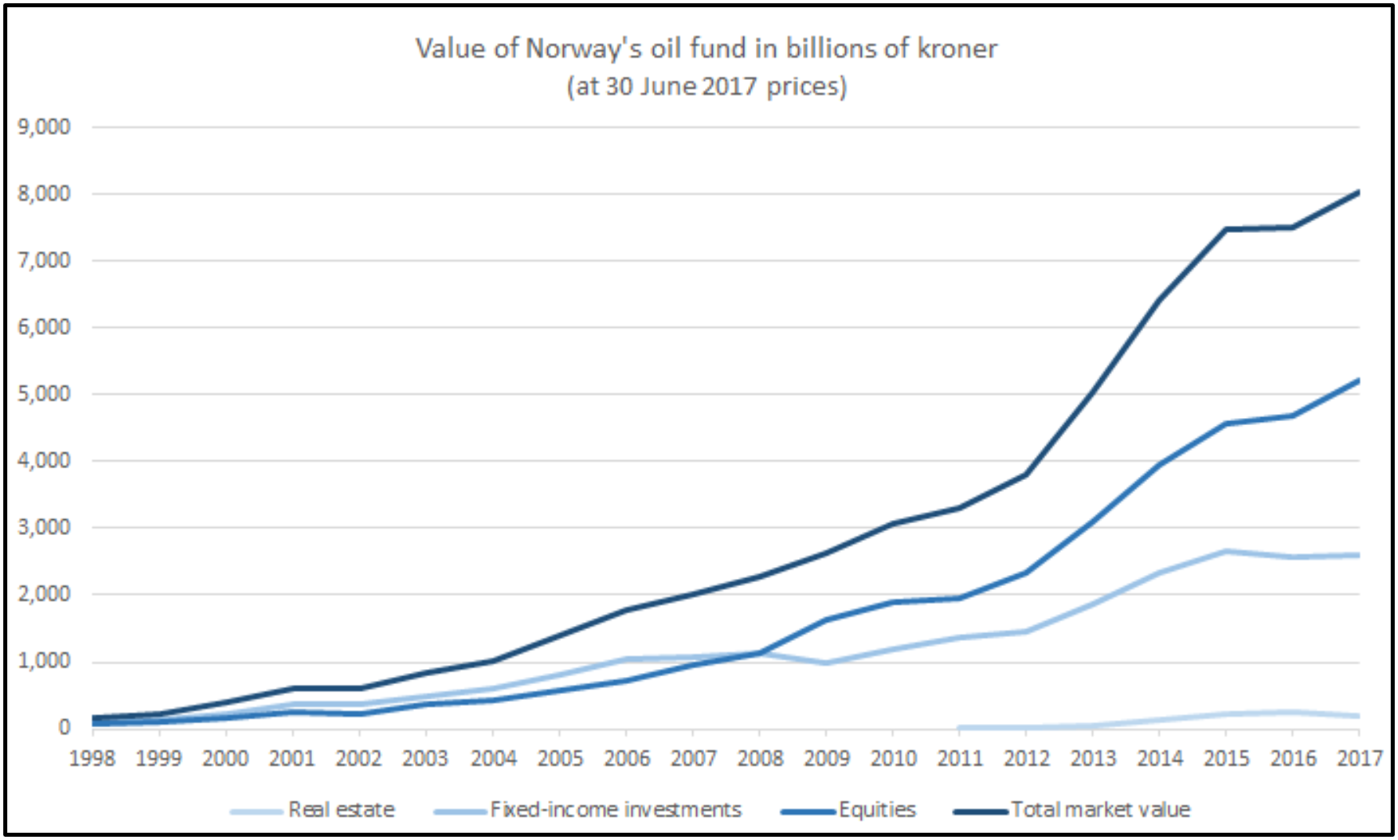

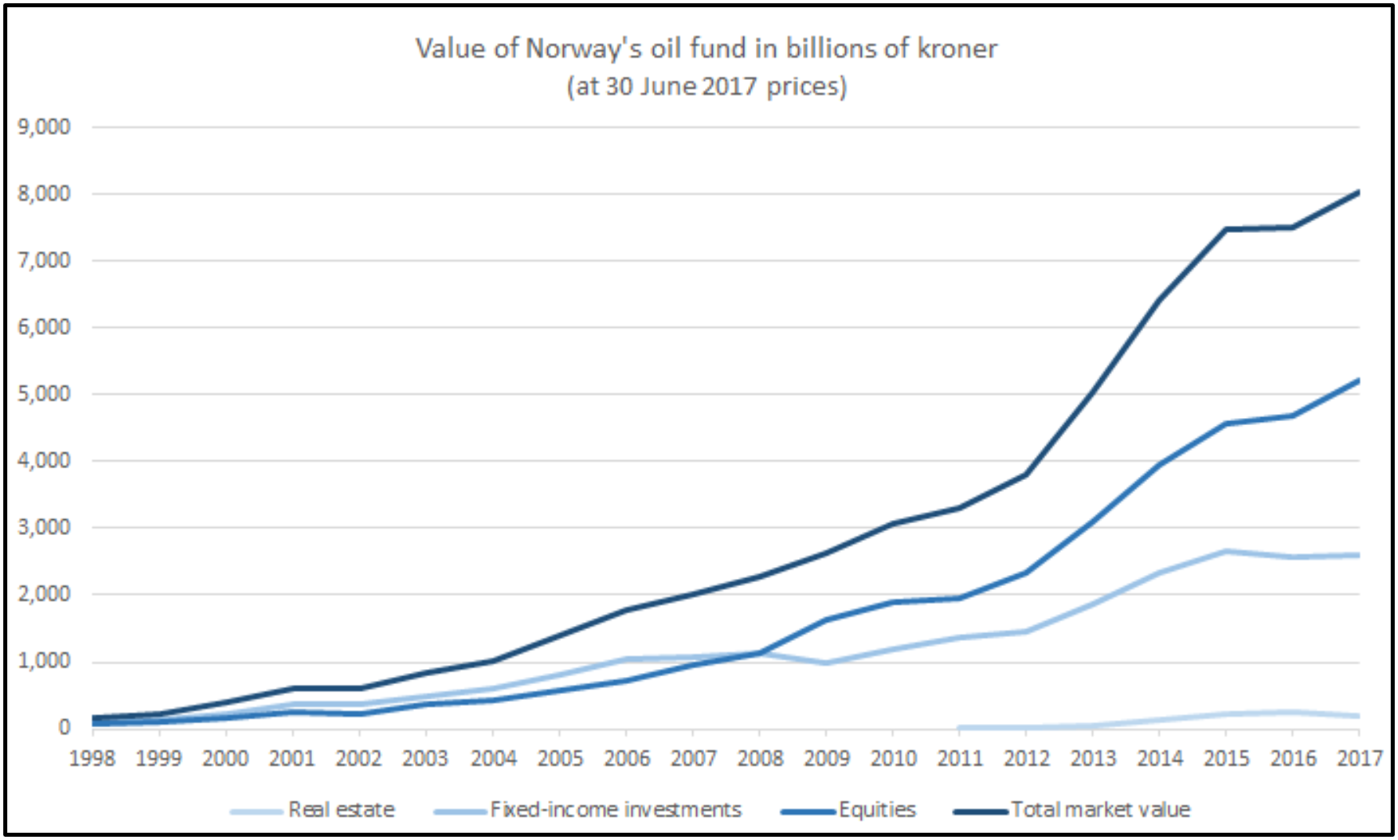

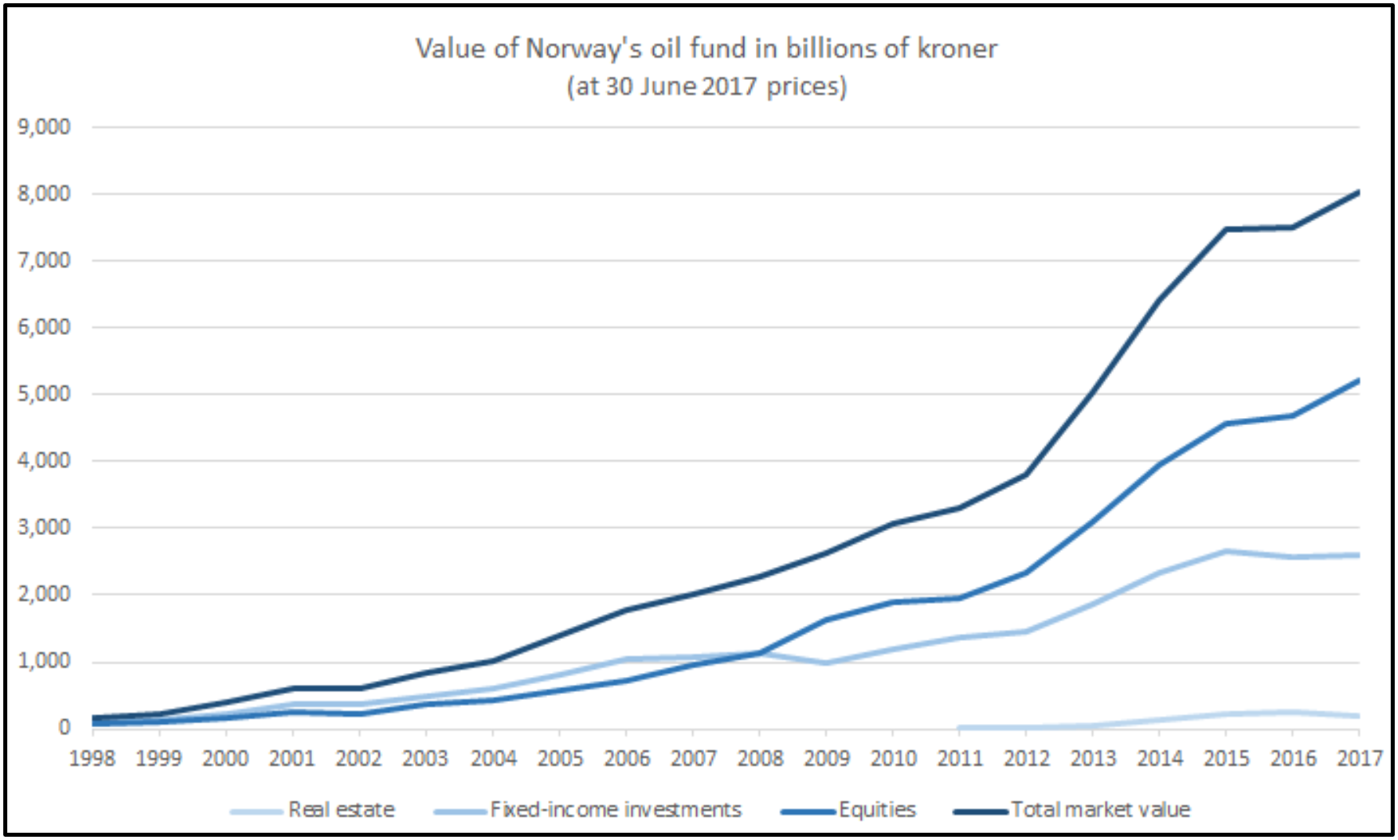

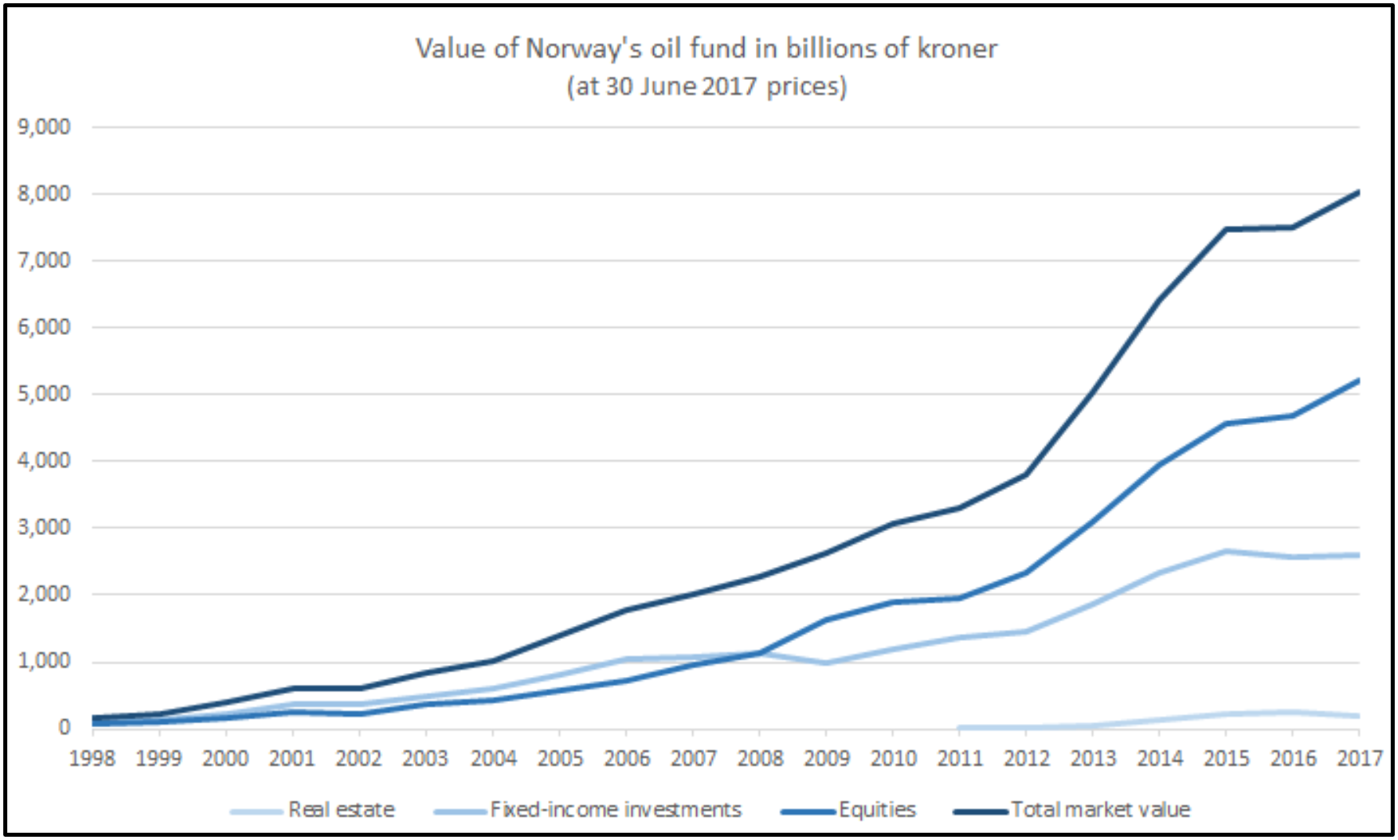

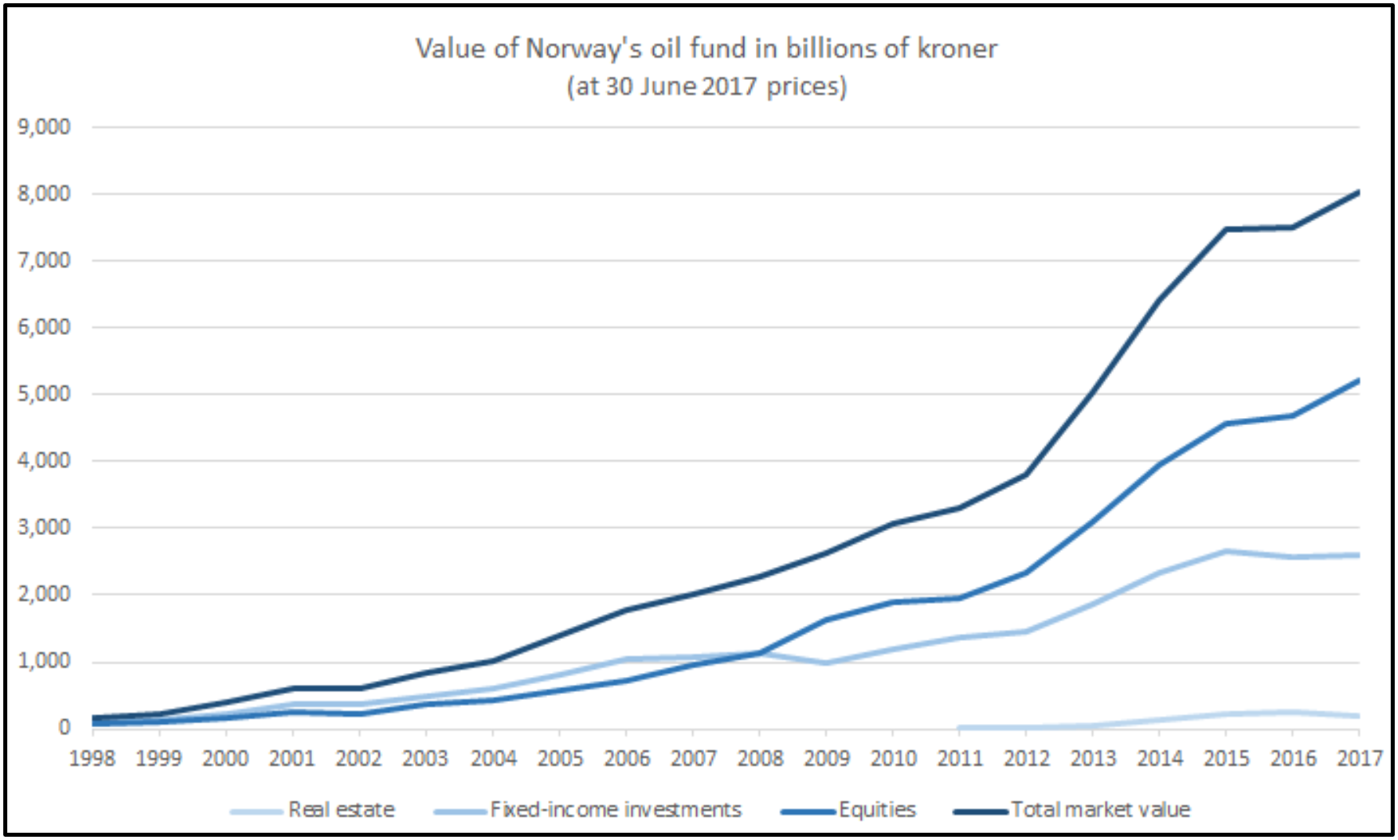

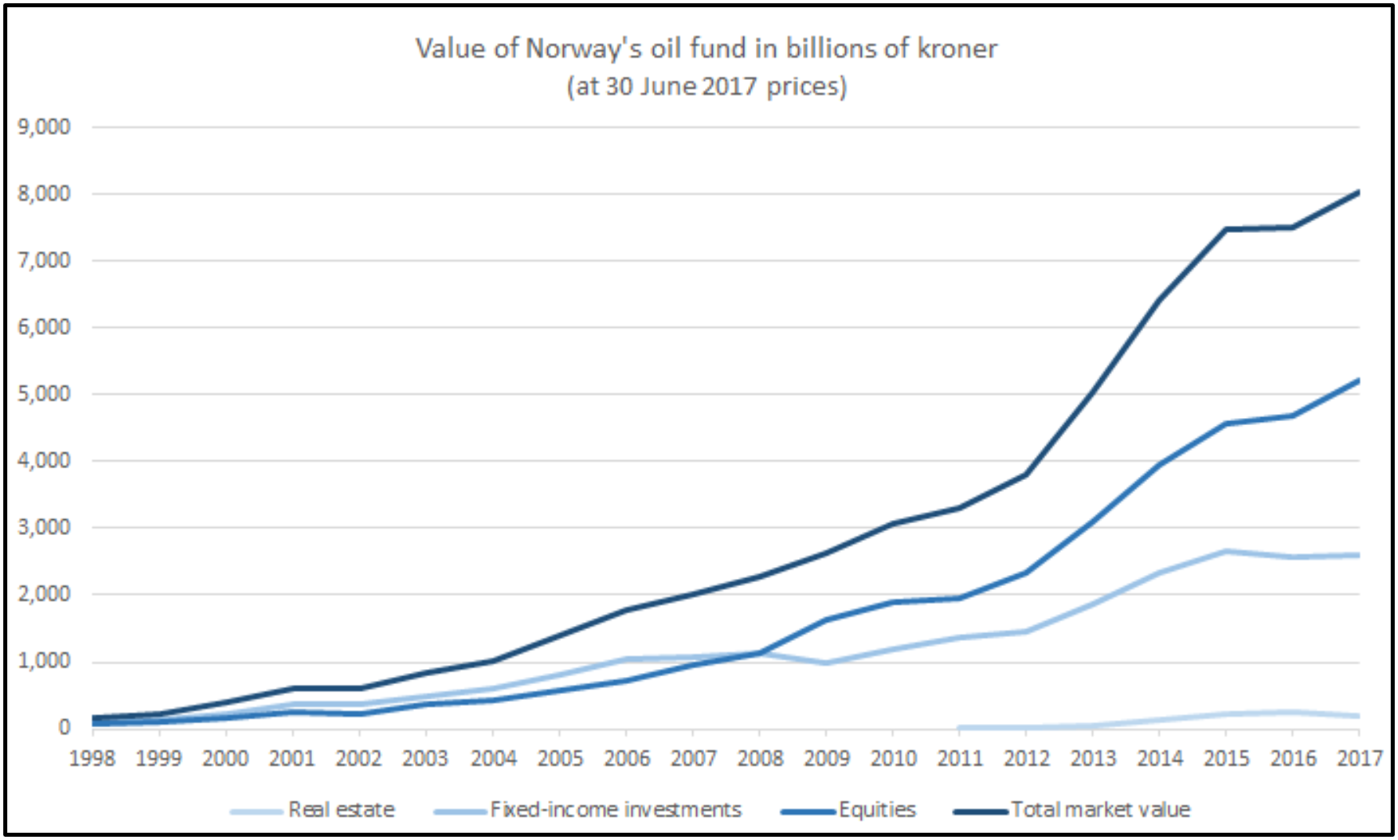

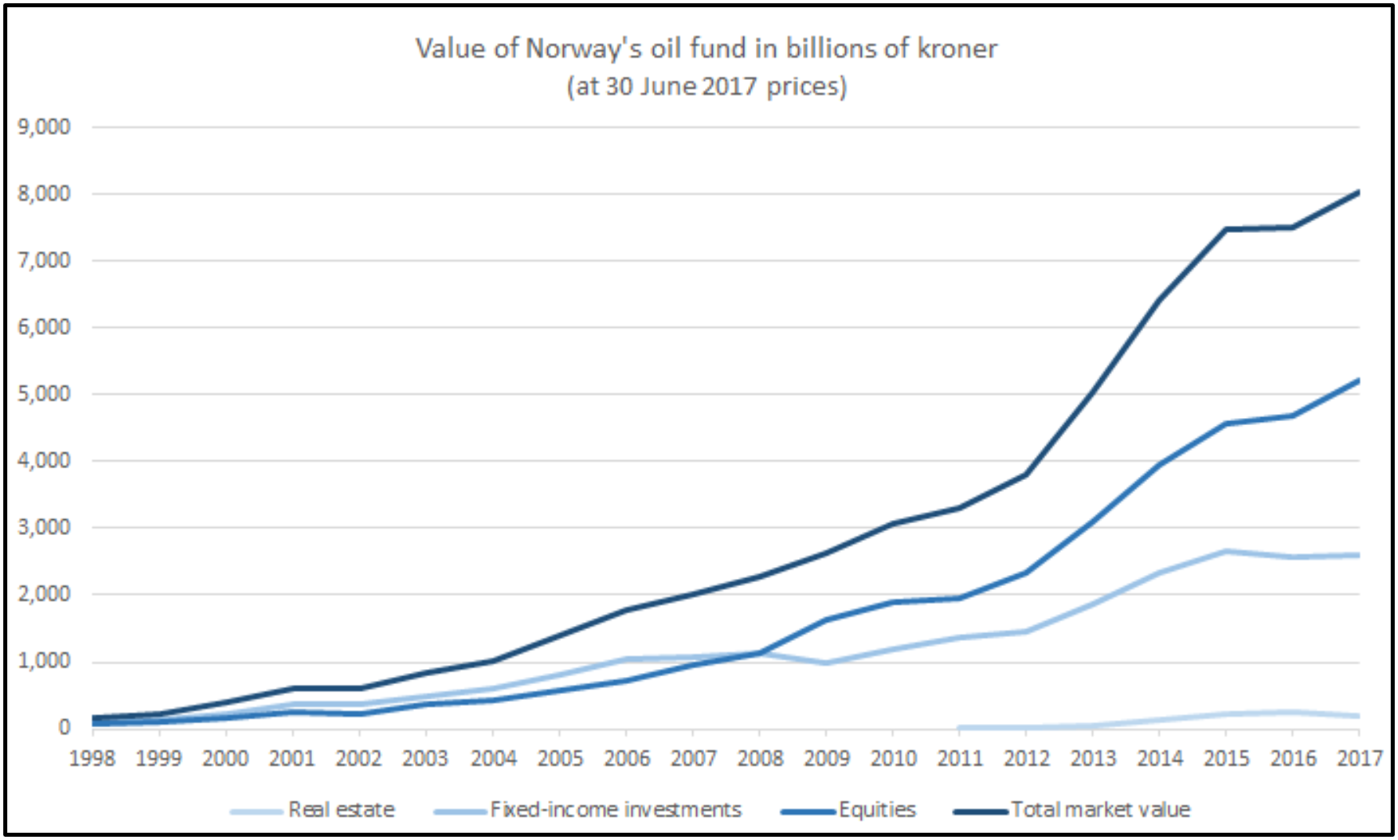

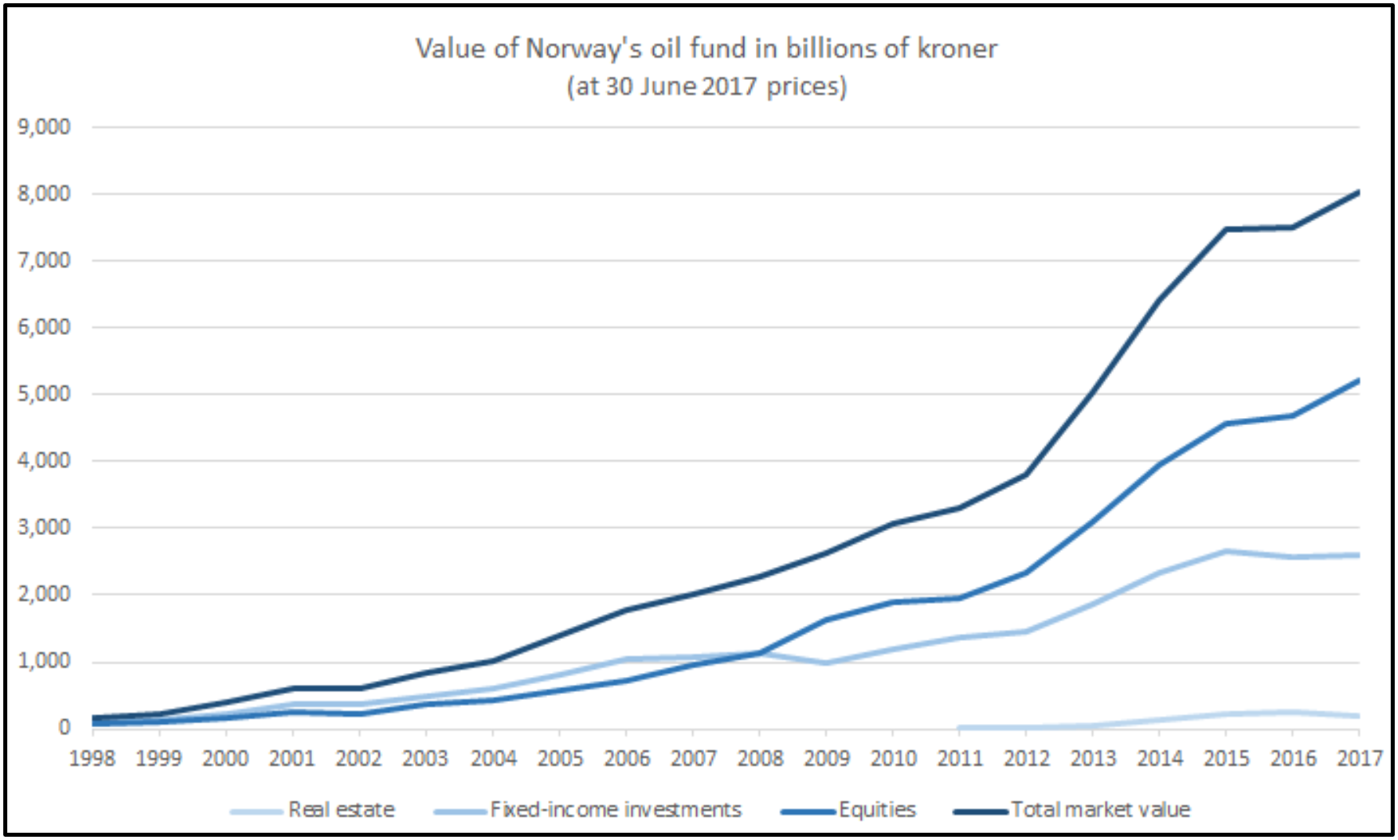

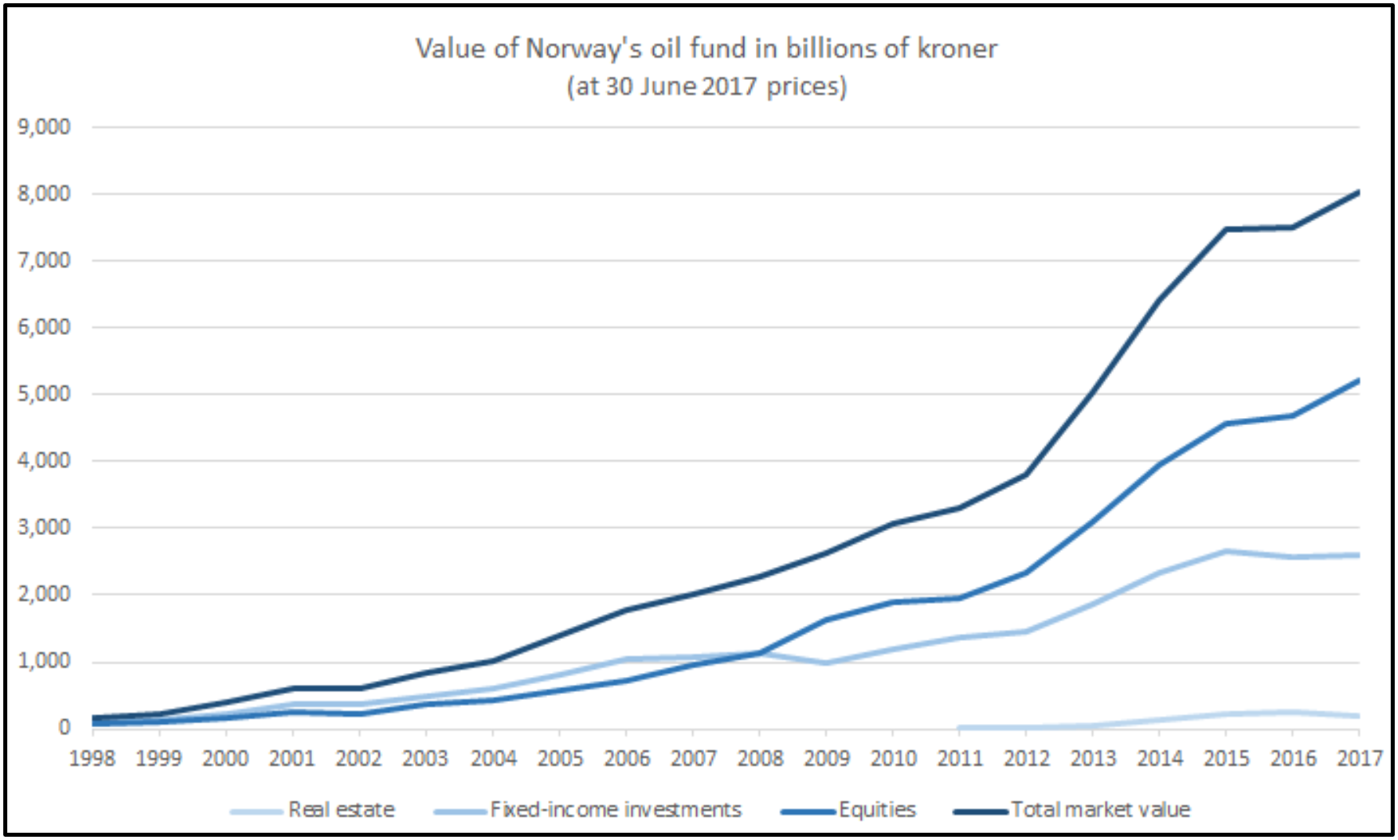

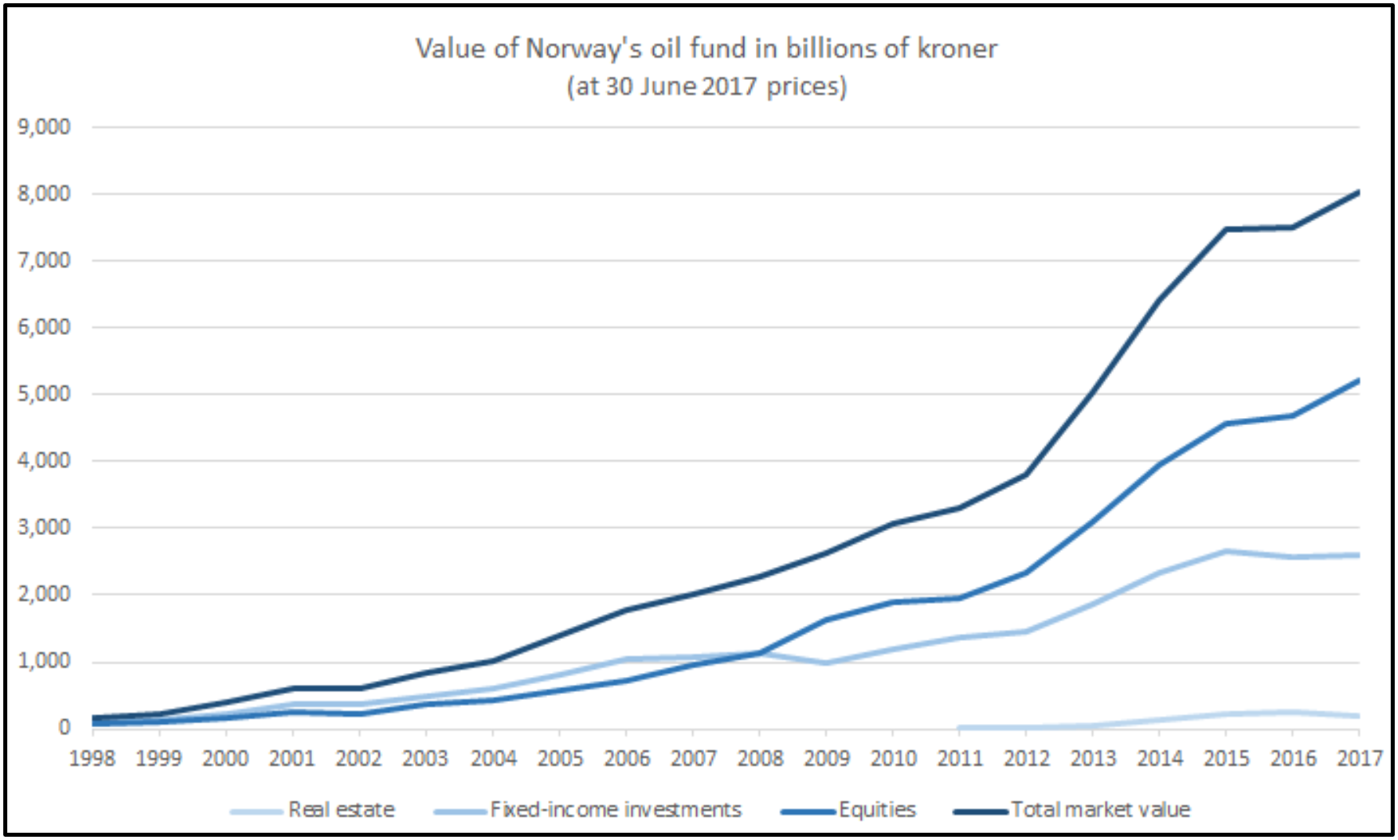

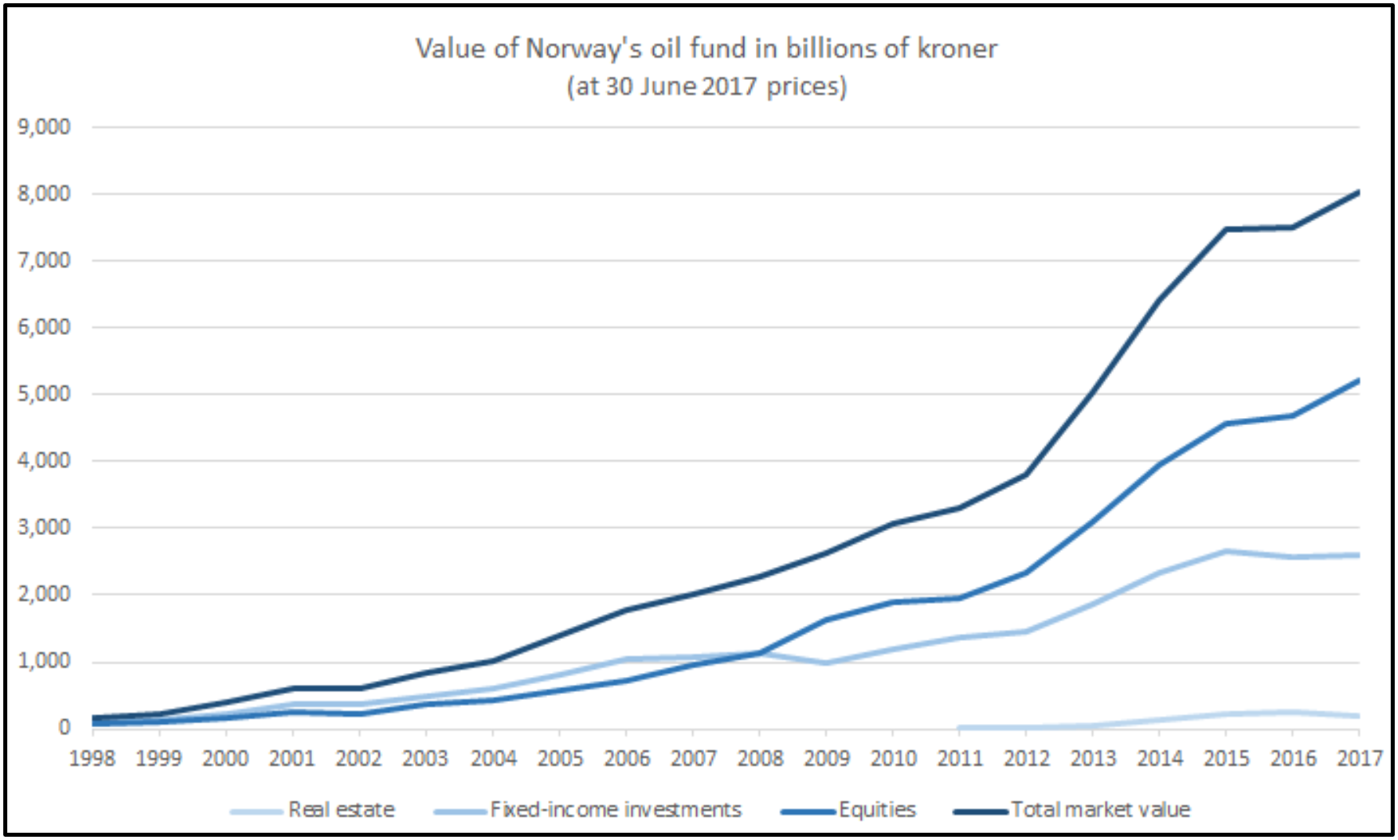

In 1996 the Norwegian government kicked the fund off with a US$255 million injection, and the fund has now grown to be the biggest sovereign wealth fund in the world, worth more than US$1 trillion, or almost US$200,000 for every man, woman and child in the country – see chart 1. After starting very conservatively and only investing in bonds, it can now invest in equities and property. In fact, this one fund owns an estimated 1.3% of the world’s shares!

Chart 1: the growth of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global

Interestingly it took until 2016 for the government to withdraw any of the funds, and one of the country’s national newspapers estimates there has been a total of US$780 million withdrawn in total. With the strong rise in oil prices in 2017 the government has stopped any further withdrawals for now. In other words, there is a culture of long-termism.

Australia

In 2003 the Chinese government ramped up spending on fixed asset investment and kicked off the biggest commodities boom in generations – see chart 2.

Chart 2: commodity prices took off in 2003 when China ramped up fixed asset investment

This had a remarkable effect on the Australian economy, starting with the Terms of Trade, which is effectively a measure of the relative strength of export prices compared to imports, and which hit a 140-year high – see chart 3.

Chart 3: Australia’s Terms of Trade hit a 140-year high thanks to the commodity boom

Likewise, Australia’s GDP started rocketing up from 2003 – see chart 4.

Chart 4: Australia’s GDP also took off thanks to the commodities boom

In fact, Paul Cleary wrote in his book, Too Much Luck, that in the three years before the GFC “the federal government’s coffers swelled by $334 billion in additional revenue”. However, in terms of putting money away for future generations from the one-off harvesting of the nation’s mineral resources, well, there’s not a whole lot to show. Cleary estimates the Howard government spent 94% of the commodities boom windfall during its tenure, then the Rudd government spent more than $100 billion trying to stave off recession during the GFC, leaving the government in debt, which has only increased since.

Peter Costello did establish the Future Fund following the 2004 federal election, but more than half the original $27 billion of principal contributions came from the government’s Telstra holding as opposed to reinvesting resources revenue, and its stated purpose is to fund public sector superannuation liabilities. And barely three years after it was set up the Rudd-led Labor opposition announced it would withdraw $2.7 billion from it. Fortunately, strong investment returns have seen the fund grow to about $150 billion now, but on a per capita basis, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global is 33 times the size.

Mining comprises 8% of Australia’s GDP and about 60% of its exports and 83% of the companies doing the mining are foreign owned. At the moment there’s no explicit plan to capture any of the current revenues for the benefit of future generations, since all the recent attempts to impose any kind of specific mining tax have been shot down. The Rudd Government tried to introduce the 40% Resource Super Profits Tax (RSPT), which prompted the resources companies to launch a $22 million advertising campaign to stop it. Ten weeks later Kevin Rudd was replaced by Julia Gillard in June 2010 and one of the first things she did was scrap the RSPT and replace it with the Mineral Resources Rent Tax (MRRT), which levied a 30% tax on resource company profits above $75 million. Then the MRRT was abolished by the newly elected Abbott government after the 2013 election.

Australian politics has just been through another episode of astonishingly shameful political short-termism. We can only hope our politicians pay attention not only to what exasperated voters are telling them but to the positive examples being set elsewhere in the world, like Norway.