Maybe the US share market isn’t as expensive as you think

The US share market has just hit a new all-time high and its returns have smashed the rest of the world for the past 15 years. But US shares also trade on valuation multiples that are much higher than the rest of the world, leaving investors who already own US companies wondering if they should lighten off, and those who don’t wondering if they should wait for prices to fall before buying in. But maybe the US market isn’t as outrageously expensive as most commentators would have us think.

America: home of the best companies, land of innovation

America is uniquely positioned, making it very difficult to bet against in the long run. Goldman Sachs points out that not only is it the biggest economy in the world, accounting for 26 per cent of global GDP, it is bestowed with an abundance of natural resources. It has the most arable land of any country and is now the world’s largest exporter of agricultural commodities, and, at 20 million barrels per day, it is also the world’s biggest oil and gas producer and exporter, with daylight to Saudi Arabia at number two with 12 million.

It also has the most favourable demographics of any developed country, the most productive labour force, and boasts the deepest capital markets, more than seven times the next biggest.

Since the late nineteenth century, the US has been at the forefront of technical innovation, boosted by some of the best universities in the world. In 2022, it was the global leader in R&D, spending US$879 billion, more than the next five countries combined.

And with exports accounting for only 12 per cent of GDP, the US economy is more resilient than most large economies because it’s less affected by cyclical downturns in its trading partners. By comparison, exports are 21 per cent of China’s GDP, 26 per cent of Australia’s and 51 per cent of Germany’s.

This is not to say the US doesn’t have its problems: it practices a brutal form of capitalism that results in a more limited social safety net, its health outcomes are an embarrassment, and its sclerotic, highly partisan political system is heavily influenced by wealthy lobby groups. Ironically, all of those problems are the result of prioritising making money.

World beating returns

It’s no coincidence that most of the best companies in the past 100 years came out of the US, culminating in today’s mega cap tech monsters.

If a smart investor had sunk $100,000 into the US’s S&P 500 index at the trough of the GFC in March 2009, and reinvested the dividends, it would have grown to be worth $946,000 by the end of 2023. The same investment in the ASX 200 would have been worth $524,000, even after including franking credits. That’s a difference of more than 80 per cent.

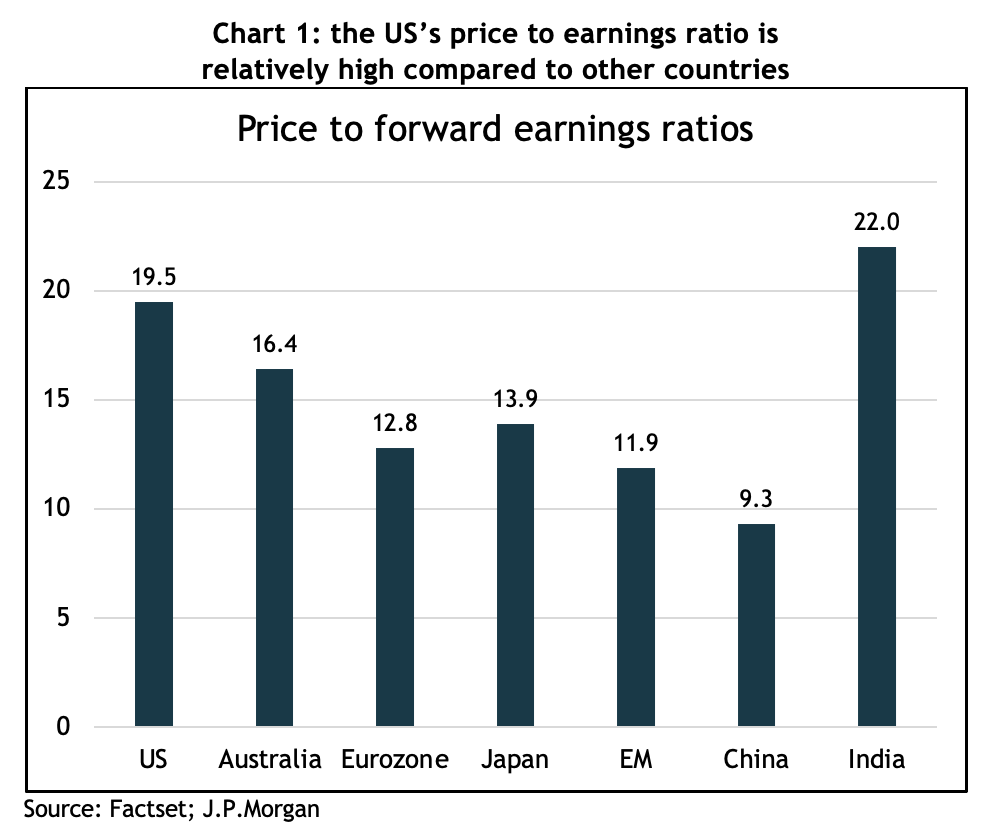

However, that incredible run has left the US share market looking expensive compared to the rest of the world. Using the most common valuation measure for shares, the price to earnings (PE) ratio, the S&P 500 trades at 19.5x 2024 forecast earnings, compared to Australia’s 16.4x, Europe’s 12.8x and the emerging markets’ 11.9x – see chart 1.

Understandably, on that basis, almost every analyst and strategist recommends an underweight position in US shares.

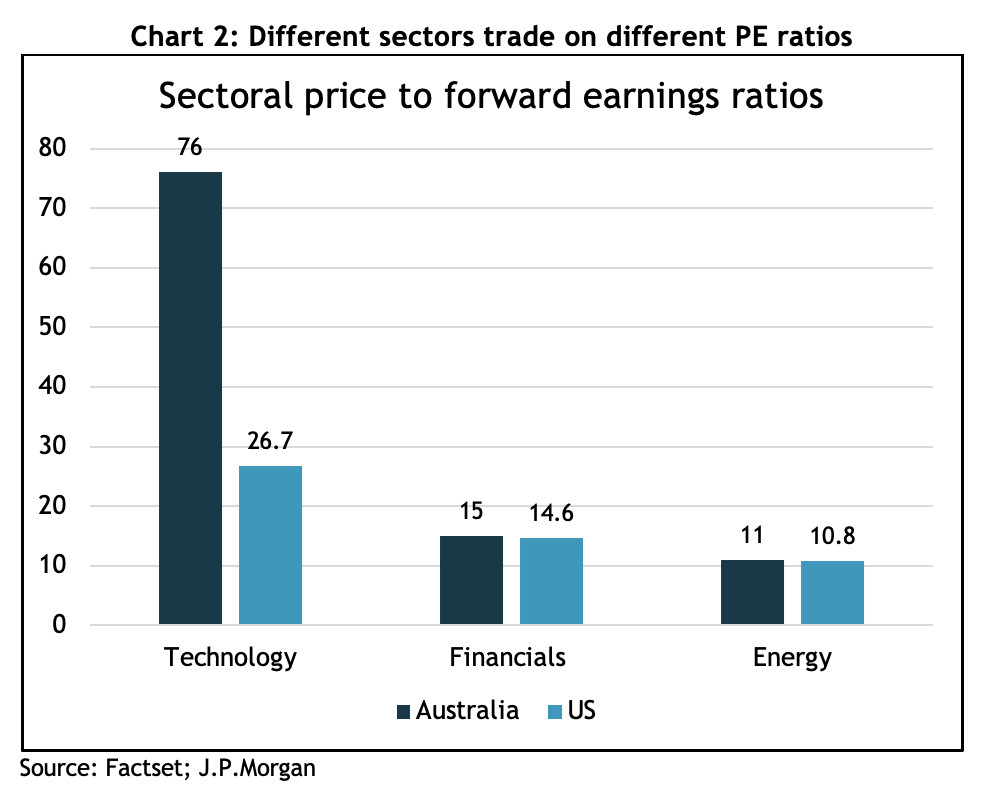

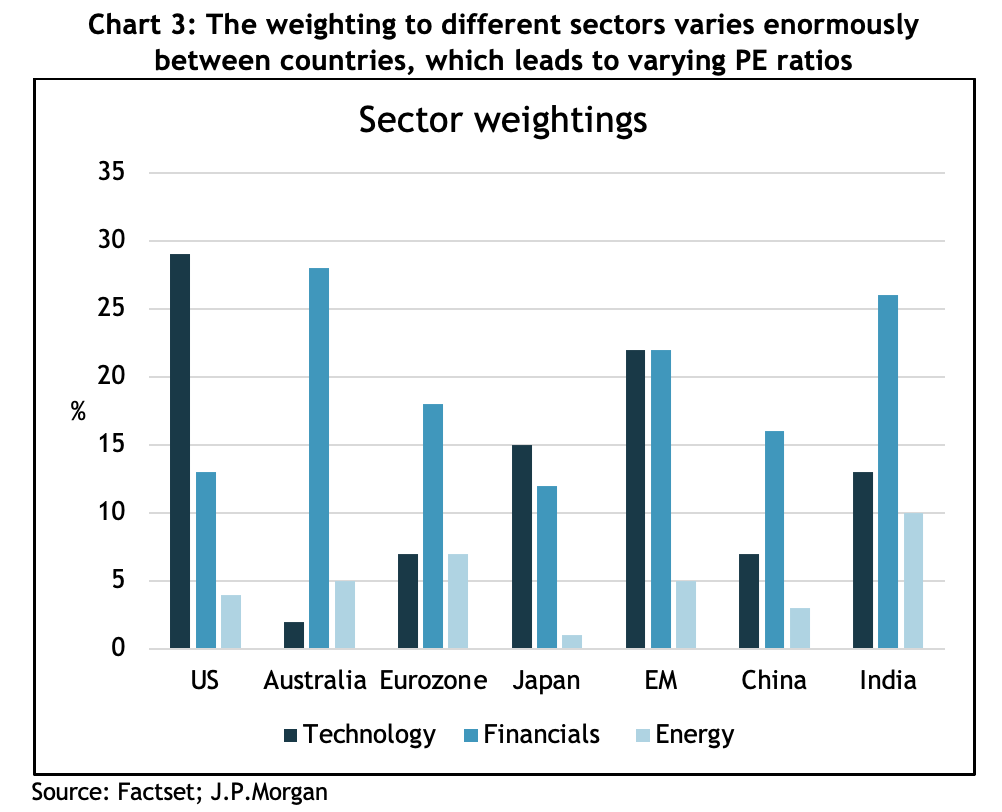

However, a simple comparison of PE ratios fails to account for the huge differences in the structure of the US market compared to others. For example, the tech sector has a 29 per cent weighting in the S&P 500, and is on a forward PE ratio of 31x, which looks very pricey, but the index has had compounded annual returns of more than 21 per cent for the past 10 years. The two biggest companies, Apple and Microsoft, have both returned 26 per cent for those 10 years, and the third biggest, Nvidia, an eye popping 63 per cent per year. It’s also worth noting that the technology index doesn’t include other mega caps such as Google, Amazon, Netflix or Meta.

By contrast, the biggest sector in the ASX 200 is the financials, at 27 per cent of the index. Its 10-year return has been 8 per cent per year, and it’s on a forward PE of 15x. So that’s 60 per cent lower returns but only a 50 per cent lower PE. If the Australian index had the same sector weightings as the S&P 500, its PE ratio would almost double.

J.P. Morgan also argues that because free cash flow margins are 30 per cent higher than they were only 10 years ago, a higher PE is justified, and fund manager, GMO, points out that since 1997, US profits, as measured by the average return on sales, have increased by 40 per cent.

It’s very difficult to mount a case that US shares are cheap, but it helps to have context around why they’ve enjoyed an outstanding 10 years of returns. There’s no way of telling if those returns will continue to be anywhere near as high over the next 10 years, but it’s hard to argue against American exceptionalism when it comes to making a buck.