Central banks and interest rates: myths vs reality

In June of last year, Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve Chair, admitted, “We now understand better how little we understand about inflation.”

That alarming, but at least honest observation from the world’s most powerful central banker, comes despite the Fed employing more than 400 Ph.D. economists who enjoy access to the world’s most up to date data.

What is truly disconcerting though, is that governments around the world have happily passed on responsibility for managing inflation, and usually unemployment as well, to central banks via the control of monetary policy. But they essentially have only one tool to do that: interest rates.

Passing on that responsibility to central banks rests on some long-standing beliefs around monetary policy that sound fine in theory but lack real world evidence to back them up.

For example, the presumption that raising or lowering interest rates can control inflation. During the 2010’s, central banks around the world were concerned about deflation, that is, inflation being too low, so the biggest central banks in the world cut interest rates to never before seen levels.

The United States had effectively zero interest rates between 2010 and 2016, yet inflation averaged only 1.6 per cent per year over that period. Over those same seven years interest rates in the Euro Area averaged about half a per cent but inflation was -0.1 per cent, and in Japan rates were stuck at zero yet inflation averaged only 0.2 per cent.

Likewise, if high interest rates are supposed to cure inflation, how is it that Argentina can have an interest rate of 78 per cent yet inflation is 102 per cent? Defenders of orthodox monetary policy would say Argentina’s long been a basket case, but that’s the point, its interest rate has been above 40 per cent for the past five years but it has failed to control inflation.

Another shibboleth of monetary policy is the so-called Phillips Curve, which asserts that inflation and unemployment are inversely related. That’s why the Reserve Bank and the Fed regularly talk about the 50-year low unemployment levels and the inflationary risk from the price-wage spiral. The theory is that low unemployment causes such high demand for workers that they will flex their bargaining power and drive up wages, so raising inflation.

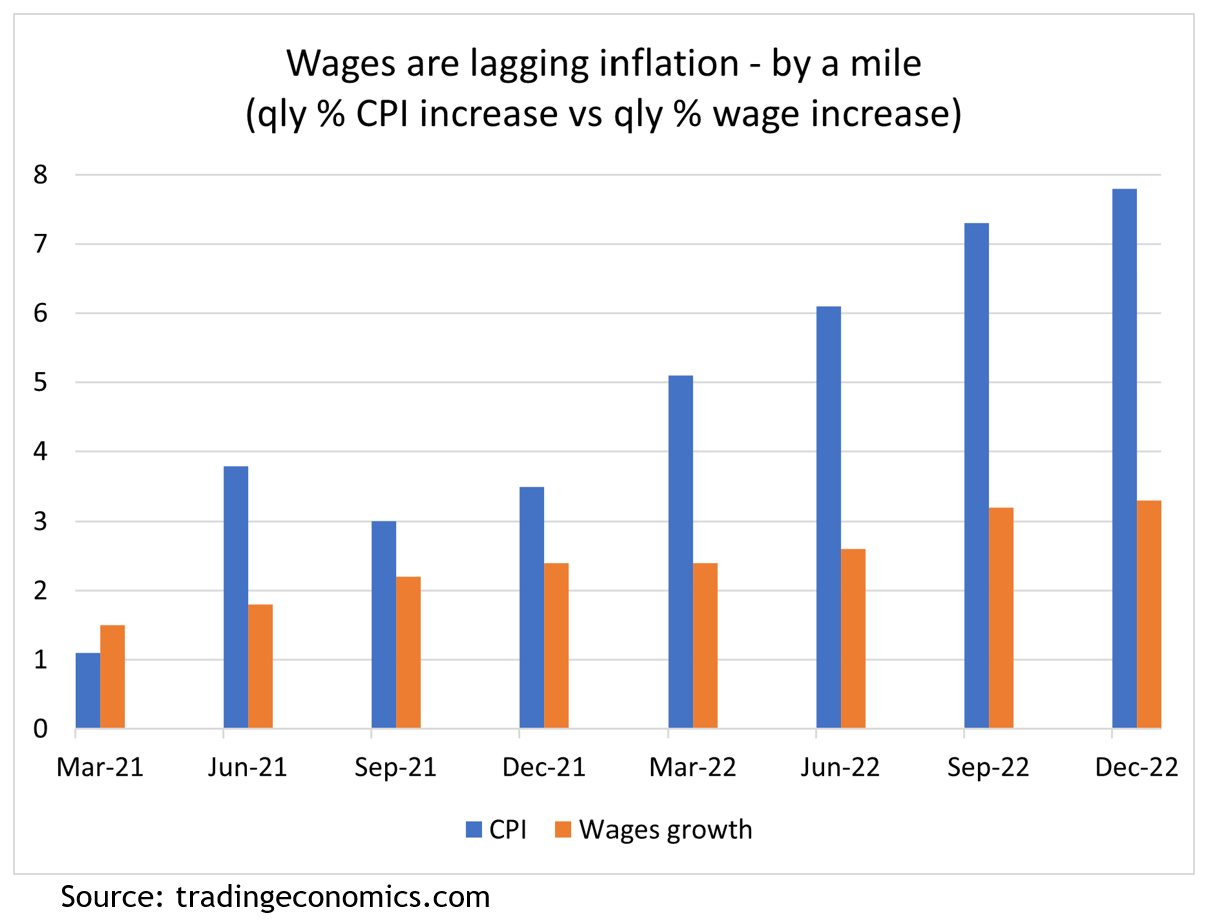

That may have been an issue 50-plus years ago when more than 60 per cent of the workforce belonged to a union, but with now only 9 per cent of Australia’s private sector in a union, things have changed. Wage increases have been below the CPI for the past nine consecutive quarters in Australia, see chart 1, and real average hourly earnings in the US declined by 1.3 per cent over the year to February, meaning it has been a deflationary influence in both countries.

Chart 1: Australian wages growth has lagged the CPI for the past 9 consecutive quarters

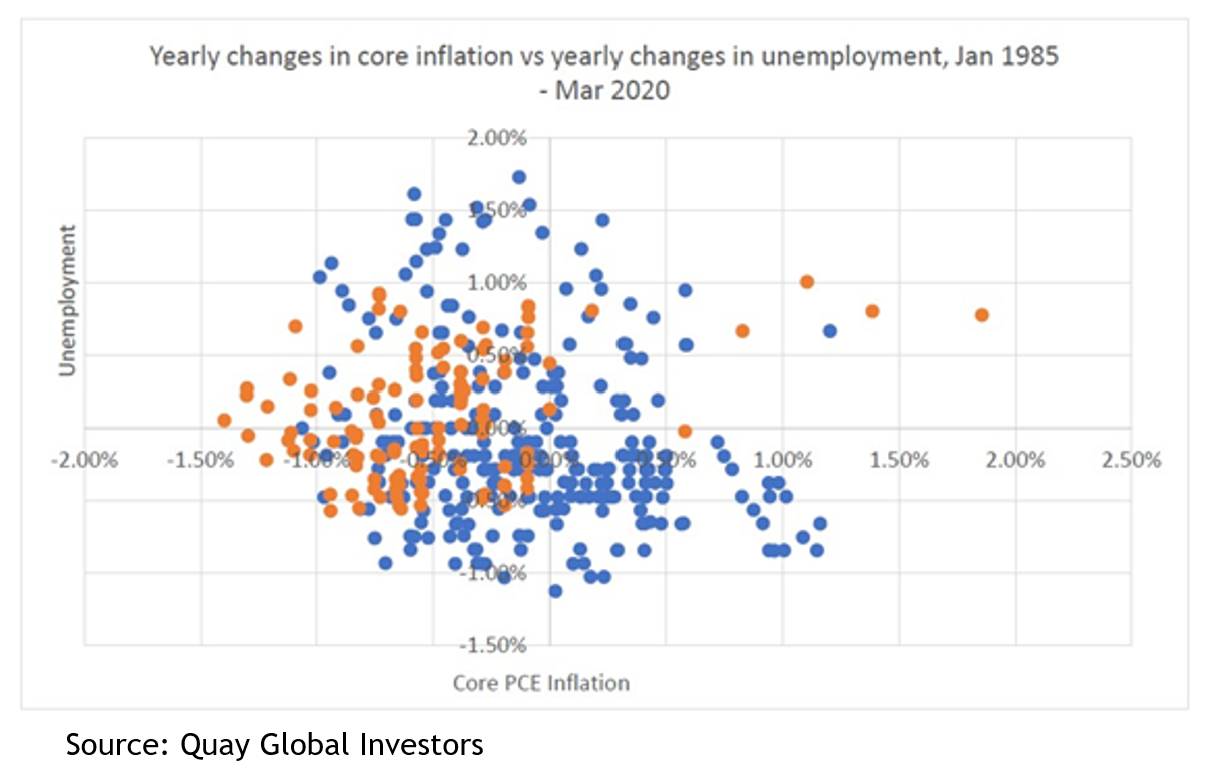

In fact, Quay Global Investors analysed the US inflation and unemployment data between 1985-2020 and found there was no meaningful relationship – see chart 2.

Chart 2: there has been no meaningful relationship between inflation and unemployment in the US over the past 40 years

However, there have now been five different analyses covering the US, UK and Australia, that have each found corporate profiteering accounts for the majority of inflationary pressures in each country. That is reflected in US corporate profit margins hitting a 70-year high last year. One of those studies dubbed the phenomena “excuseflation”, because companies were using the first bout of inflation in years as cover to raise prices as much as they felt the market would bear.

Yet central banks continue to focus on consumers and households, with no mention of the role played by companies. By contrast, at the start of the pandemic the Japanese government made it clear to companies they would be watching for opportunistic price gouging, resulting in an inflation rate that peaked at about half the rest of the developed world, despite importing almost all their food and energy.

Also, monetary policy is frequently, and correctly, referred to as a blunt instrument because it can only work indirectly, by encouraging or discouraging people and businesses to borrow money and it can take ages to have any effect. The usual expression is that it operates “with long and variable lags.” However, all the central banks continue to say they will be “guided by the data”, but that data, be it the CPI, unemployment or industrial data, is all backward looking. There is an obvious logical mismatch.

Another logical mismatch is expecting that raising interest rates, which can only influence demand driven inflation, will do any good against supply driven inflation. For example, the floods last year contributed to double digit food inflation. Obviously, families have to eat, so raising interest rates is entirely non-sensical as a way to counter those inflationary effects.

The very clear problem is that by sticking dogmatically to those underlying economic theories, without accounting for the lack of real world evidence to back them up, central banks risk pushing economies into recession. Central bankers are muscling up trying to show they can be as tough as Paul Volcker, who was credited with stopping the inflationary episode of the 1970s-80s, but there are compelling arguments to suggest he gets way too much credit. They insist the pain of inflation, which by their own admission they don’t fully understand, is worse than the pain of people losing their jobs or their houses.

Interest rates can definitely play a role, after all, if central banks push interest rates high enough they will inevitably force a recession, which will certainly have deflationary consequences, but it’s ridiculous to argue that’s the only way to address the problem.

There are no easy solutions to controlling something as mysterious as inflation in a modern, complex economy, however, acknowledging the critical role fiscal policy plays would be a start. Professor Isabella Weber of the University of Massachusetts, who specialises in inflation, argues governments should explore strategic price controls, which have been extremely effective in the past, such as during war times.

However, until the dogmas of orthodox economic policy are left behind, smart investors need to remember to base their investment decisions on what they think will happen, not what should happen.