The global bull market since the end of the GFC has been characterised by what feels like a few extremes: super high liquidity, super low interest rates and super low inflation. Understandably, there is concern that if one of those three elements changes it could spell the end of the bull market. Is that concern justified? In short, yes. What should you do about it? Well, there’s no real short answer for that.

Why low inflation matters

There are a few things affected by inflation that in turn influence markets: bond yields, interest rates and PE ratios.

BOND YIELDS: Inflation is like kryptonite for bonds: when it looks like inflation is going up bond prices go down and bond yields, which is basically the interest those bonds pay the investor, go up, because bond yields move in the opposite direction to prices.

In turn, rising bond yields can affect the price of a whole universe of financial assets, because those assets are valued using a ‘discounted cash flow’ (DCF). That means you try to work out how much you’re willing to pay for an asset (like a company or some shares) by calculating what the future cash flows you’d earn from owning the asset are worth today.

To calculate the DCF you use a ‘discount rate’, and that is normally the 10-year bond yield. If that bond yield goes up, the DCF valuation will go down. That’s one of the reasons given for the rise in asset values over the past few years as bond yields kept declining, and that, of course, could slow right down or even go into reverse if those bond yields go up.

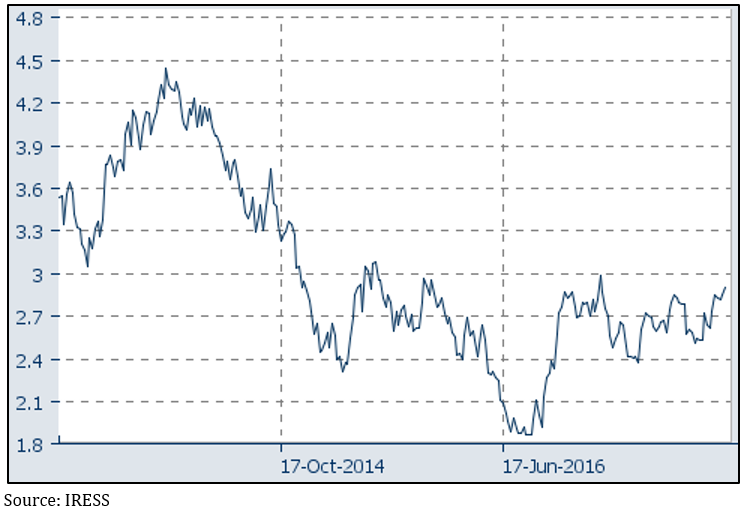

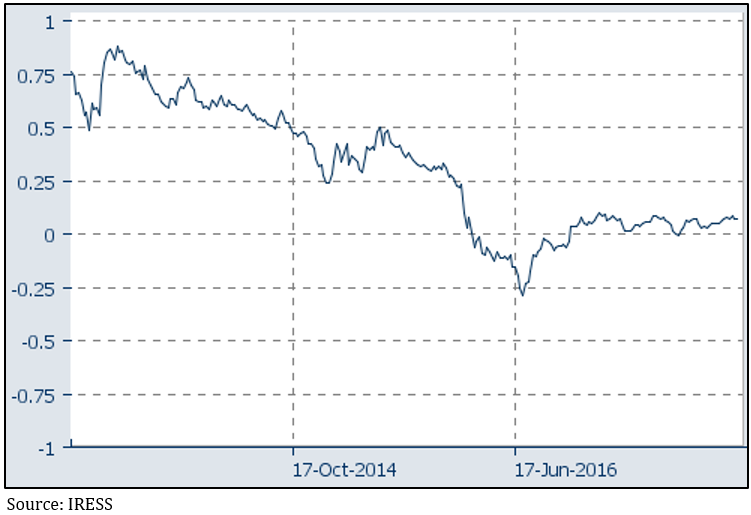

So what’s happened to bond yields lately? They’ve gone up, but they’re a long way from being what you’d call high and they reflect the different phases the various economies are in – see charts 1 to 3.

Chart 1: US 10-year bond yields are a long way off their lows, but an even longer way from their highs

Chart 2: the Australian 10-year bond yield is also off its lows and shows how the US and Australian economies are very different phases right now

Chart 3: While Japanese 10 year bonds have also risen, they are barely positive at 0.07%

INTEREST RATES:

central banks set cash rates partly based on what they think is happening with inflation. Some may remember the cripplingly high interest rates of the early 1980s when the US Federal Reserve, under the governorship of Paul Volcker, set out to crush 10% inflation by hiking interest rates to record high levels of 20%!

Over the past few years central banks have been more worried about inflation being too low, which in turn helped justify keeping interest rates very low. Obviously, if inflation looks like it could get out of hand you’d expect the central banks to raise interest rates faster than what the market would otherwise have factored in.

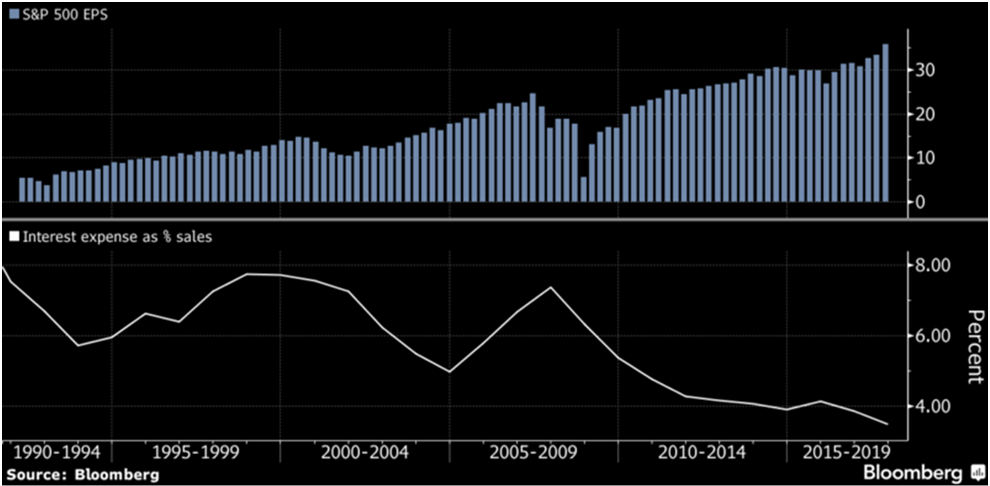

According to Bloomberg, rising US stock prices have been supported by super low interest rates that helped cut the cost of servicing debt for companies in the S&P 500 to an all-time low of 3.5% of sales over the past 12 months, compared with 7.4% in 2007. That amounts to US$320 billion in savings that boosted profitability and would be threatened by rising interest rates – see chart 4.

Chart 4: low interest rates have resulted in record low debt servicing costs, making US companies more profitable

The other risk is that rising interest rates will feed through to the housing market and slow borrowing and roll on to reducing consumer spending.

So what’s happened to interest rates lately? The only major economy that has seen official interest rates go up in the past few years is the US, where the Fed has raised rates five times from the record low 0.25% to the still very low 1.5%. All eyes are on the Fed to see how they’ll react to the recent strong economic news out of the US.

PRICE TO EARNINGS (PE) RATIO:

changes in the PE ratio can be the most important factor in determining where a stock market trades. A high PE ratio generally reflects a more buoyant market, that is, investors are willing to pay a higher price for a given level of earnings.

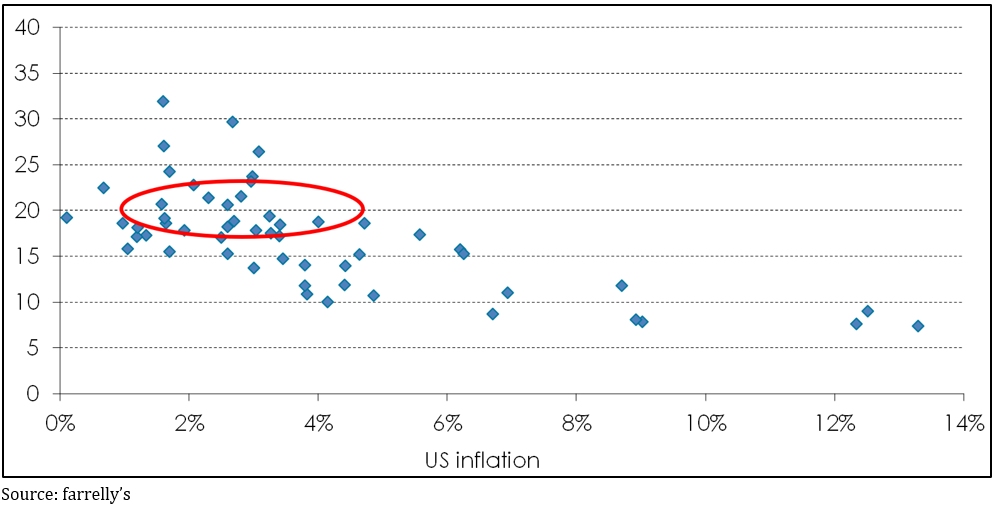

Historically, low inflation also tends to see higher PE ratios – see chart 5. Whether that’s because low inflation makes investors feel more buoyant is actually a pretty complex question, but over the past 10 years the US’s PE ratio has gone from about 11 to 18.

Chart 5: US PE ratios vs inflation

What should you do about rising inflation?

If rising inflation can have negative consequences for equities markets what should you do about it? Apart from being wary about your bond exposures, the timing of market reactions to changes in inflation is, like all questions of market timing, next to impossible to predict.

Likewise it can be difficult to know which way the markets will jump given particular inflation data; it’s frequent you’ll see markets react counter intuitively.

It comes back to basics: a well-diversified portfolio will often be the best protection against negative market surprises, including inflation.