This article appeared in the Australian Financial Review.

Last week, Seth Klarman, a US-based billionaire hedge fund manager, launched another of his many attacks on the US central bank, claiming that by treating financial markets like children the Fed has created “surreal” conditions that are detached from reality. Klarman is just one of many fund managers who complain so frequently that markets are being propped up by central bank liquidity that it has become all but accepted as a fact.

It’s a seductive narrative: the central banks are printing money, which has to go somewhere; asset prices have risen, especially in the US, so that must be where the money’s gone. However, the evidence simply doesn’t support it.

The usual culprit these critics point to is Quantitative Easing, which is typically referred to as QE. First, it helps to understand how QE works: take an investor that sells $1 million of government bonds to the Fed, which in turn pays them $1 million in cash. Even if the investor hangs on to the money instead of putting it in the bank, there’s no net change in the amount of money available to the investor. One government issued asset has been swapped for another government issued asset, and in fact, to the extent that cash doesn’t pay any yield like a bond does, the investor is slightly worse off.

The critics assert that because the central banks are buying government bonds and consequently keeping yields lower than what they otherwise would be, those freshly cashed up investors have been forced to buy riskier assets, like shares, to get the required return.

However, this overlooks two points. First, it would be highly unusual for a bond investor to switch to shares, regardless of the return, since bonds are considered a defensive asset while shares are a growth asset. Second, equity funds have been suffering net outflows for years, to the point where last October US equity funds reported more than $100 billion of outflows over the calendar year while bond and cash funds had seen $790 billion of inflows.

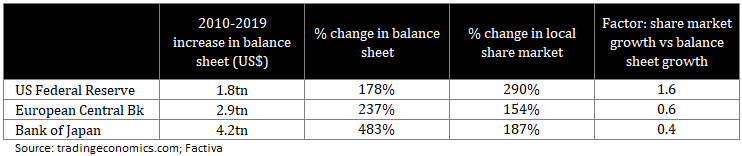

The three biggest central banks undertaking QE over the ten years to the end of 2019 were the Fed in the US, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The Fed increased its balance sheet by 178% over the decade, during which time the S&P 500 went up by 290%, so the share market went up by a factor of 1.6 compared to the balance sheet. The ECB’s balance sheet increased by 237%, but its shares only rose by 154%, so a factor of 0.6, and the BOJ’s balance sheet rose by a whopping 483%, but its shares increased by only 187%, a factor of 0.4. In other words, there is no clear relationship at all between the level of central bank activity and share market returns.

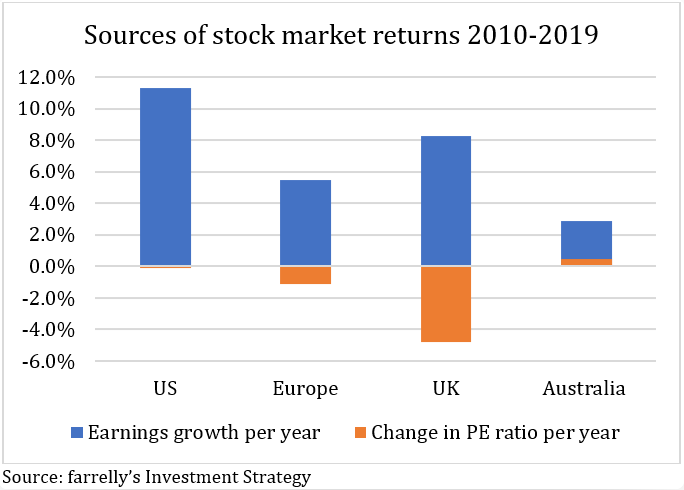

Tim Farrelly, of farrelly’s Investment Strategy, points out that, “The idea that central bank liquidity drives markets has a sliver of truth to it in that keeping interest rates a little lower than they otherwise would be assists valuations. But all the evidence suggests earnings explain much more about market returns.”

There is no doubt central bank activities have been critical to markets recovering in March this uear, but that was by unclogging the credit markets and allowing that essential corporate lifeblood to flow again.

So why does the false narrative persist? Partly because it’s intuitively appealing, but mostly because it’s repeated endlessly by fund managers looking for excuses as to why they’ve underperformed their benchmarks. It’s much easier to blame central banks for markets being detached from fundamentals, than to admit you’ve got it wrong for 10 years. The important lesson for investors is to ignore the conspiracy theories and stick to fundamentals.