After nothing but negative headlines for months, since the re-election of the Liberal government there’s been a sharp about-face for the Australian property market. In quick succession the risk of doing away with negative gearing and halving the capital gains discount rate vanished, then the Reserve Bank governor flagged lower interest rates and then the banking regulator lowered the qualifying hurdle for borrowers.

So you’d think it should be happy days for potential property investors: saddle up and back to the races! Not so fast.

If you take the time to think things through, there are still plenty of warning signs, especially for those looking to buy a residential investment property in Melbourne or Sydney.

Speculating is not investing

CoreLogic reports the average gross rental yield for residential houses in Melbourne and Sydney is 3.6%. But to work out if that’s a good investment you have to deduct all your expenses to arrive at a net yield: that includes income tax, agent commission, land tax, body corporate fees, insurance, maintenance costs, and what have you. When we work out a client’s net yield it’s typically between zero and one percent.

By contrast, a six-month, government guaranteed term deposit currently pays you 2.5% gross. For someone on a 37% tax rate that’s 1.6% net, with no other costs to worry about.

When an asset is yielding less than what’s called the ‘risk free rate’ (and you don’t get much more risk-free than government guaranteed), the only way you can justify investing in it is making a capital gain, and, by definition, that makes it a speculative asset.

Compare assets

Commercial property on the east coast yields about 5.5% – that’s a 50% premium to the residential average. Don’t fall into the trap of saying, ‘but commercial property prices don’t go up as fast as residential’, remember we’re talking about investing here, not speculating.

The other classic growth asset is, of course, shares, and the most common valuation measure for shares is the price to earnings (PE) ratio, which is simply the price you pay divided by the net earnings you receive. At the moment the ASX200 is on a PE of 16.5, but for a rental property with a net yield of 1% that’s a PE of 100!

The only way you can explain that difference is debt, which always lies at the heart of every property boom, and that’s where the Australian residential property market looks really risky.

Too much debt

According to the Bank of International Settlements, at 120%, the ratio of Australia’s household debt to GDP is second only to Switzerland’s and compares to the average for developed economies of 72%. For context, to look at three other recent debt-driven housing booms, the same ratio for the US at the peak of its pre-GFC property boom was 99% (it’s now 76%), Ireland’s was 117% (now 44%), and Spain’s was 85% (now 60%).

The Reserve Bank reports Australian household debt to disposable income is now 190%, up from 160% in 2012 (and about 110% 20 years ago), yet only 37% of homes have a mortgage! Underlying that, in Sydney and Melbourne the loan to income multiple went from the old rule of thumb of three times, to now about six.

Again, for some perspective, Sydney’s house prices rose 80% between 2012 and the 2017 peak and Melbourne’s went up by 56%. By comparison, US house prices rose 78% over the five years to their peak in 2006, Ireland’s prices went up 100% in three years and Spain’s by 50% in four years. Now, about 18 months after they peaked, Sydney property prices are down 15% and Melbourne’s by 11%. From their peak to trough US prices fell 34%, Ireland’s 55% and Spain’s 35% and the average time from top to bottom was just short of six years.

Banks and incentives

To understand what’s going on in the housing market it helps to understand how we got here.

In 1988 the first Basel banking accord was released, which halved the capital banks had to keep on their balance sheet against residential mortgages. That meant the banks’ Return on Equity, or profitability, doubled overnight.

[Explainer: if a bank has to retain $20,000 of capital on its balance sheet against a $100,000 loan, on which it charges an interest rate of 5% per annum, its return on equity (ROE) is $5,000 (interest) on $20,000 (capital), so 25%. If the capital buffer is halved, it’s $5,000 on $10,000, so 50%. Bingo, the ROE doubles overnight.]

The Australian banks, coming off an existential crisis after over-lending to the ‘80s entrepreneurs like Bond and Skase, jumped on this newfound source of profitability so enthusiastically that our so-called ‘commercial banks’ have swung from housing being one-third of their loan books to now being two-thirds. That has required a 30 year, industrial scale campaign of shoving as much debt as they can into the sector, aided by tailwinds of declining interest rates, tweaking the tenure of loans from 20 years, to 25 and now 30, and the rocket fuel of interest only loans.

Why did they do that? Because it kept their profits high.

And the upshot? Over the last 10 years mortgage debt has grown at 7% per annum, while real wage growth has been 2.5%. In Melbourne, between 1960 to 1988 the multiple of average wages required to buy the median-priced home went from 2.8 to 3.9; but then between 1988 to 2018 it went from 3.9 to 10.3!

More debt in an over-indebted sector

The cheerleaders for the property market are back in force, but their assertion we’ve seen the bottom in house price declines is based entirely on more debt being taken on. That response is very much level one, or kneejerk, thinking: just because you’re able to buy a house doesn’t make it good value.

Clearly the Reserve Bank is worried about the effects of falling house prices on the broader economy: an Assistant Governor gave a speech chastising the banks for being ‘stingy’, they leaned on APRA to quietly reopen the interest only lending taps just before Christmas last year, they’re openly flagging lower interest rates and APRA’s eased up on the lending benchmarks the banks have to use. Every one of those actions is designed to throw more debt into an already over-indebted sector.

The cries of relief that negative gearing won’t be abolished also breaks another rule of sound investing: you never invest in an asset based on tax breaks. It should always stand on its own feet.

After 30 years of debt-fuelled rising property prices, the ‘anchoring bias’, where peoples’ expectations are shaped by past experience, will be hard to shake. But behavioural economics tells us as investors, our best decisions are made when you engage second-level thinking and look beyond your biases.

Some extra facts

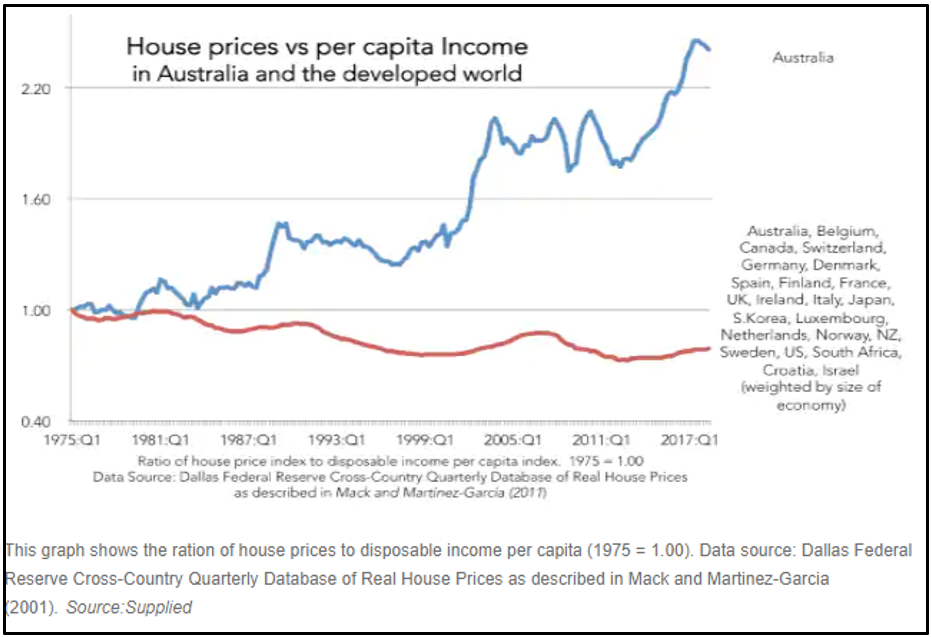

* Debt-driven housing markets: have a good look at this chart and then ask yourself how it is Australian house prices could have gone up by so much more than per capita income. The answer is more and more debt.

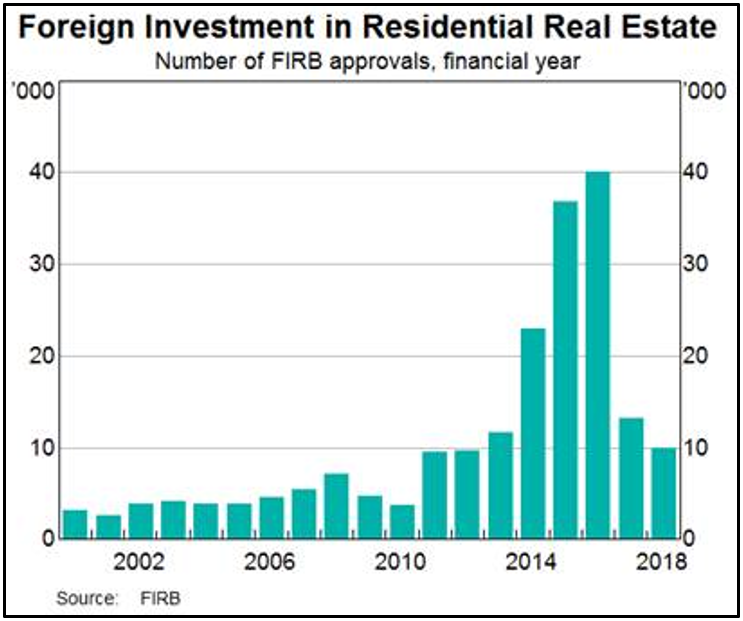

*Dramatic fall in foreign buyers: Foreign Investment Review Board approvals of foreign residential real estate purchases for 2018 were one quarter of what they were in 2016.

*The crane index: Per Ashley Owen of Stanford Brown – In April 2019 there were 735 high rise cranes on the skylines of Australian cities, which was more than the whole of the USA. 72% of these cranes were for residential units, so the RBA’s long hoped for shift from residential to commercial and infrastructure had not happened. The last time one country dominated the world crane market was Dubai in 2010 and that ended in Dubai’s dramatic collapse and bailout. House prices in Dubai are still lower now than they were 10 years ago – and that’s before inflation.

*An increase in supply: in February, Core Logic reported there were more houses up for sale than at any time since 2012. With 115,000 houses listed across the country, it was 15% higher than the same time in 2018.

*Mortgage stress on the rise: in March 2019 S&P said the number of borrowers more than three months behind on their mortgage repayments doubled over the last decade, a sign of a “persistent rise” in the severity of home loan arrears. About 60 per cent of borrowers overdue in repayments are currently overdue by more than three months — this is up from 34 per cent a decade earlier.

*Australian banks are clamping down on how much they’ll lend…: in November 2017, the Commonwealth Bank’s “how much can I borrow” calculator estimated someone on the average annual salary at that time of $80,278 could have borrowed $463,000. By April 2019 that had dropped almost 25% to $351,100.

*…but it’s not a credit crunch, just sensible lending standards: the bank ‘lending crackdown’ is not a credit crunch, as some describe it, it’s actually a return to prudential lending standards that should never have changed in the first place. It was symptomatic of the banks’ enthusiasm to lend as much as possible for residential property, because of the high ROEs, that they were prepared to waive through loan applications that failed to properly assess a borrower’s spending.

Prior to that ‘crackdown’, instead of individually assessing a loan applicant’s spending, banks were frequently using the Household Expenditure Method (HEM), which presumes a certain level of spending based on postcode, the number of family members and salary. However, it was easy to fudge numbers and it could leave out critical amounts like school fees. At one point as many as 75% of loan applications relied on the HEM, which, if nothing else, is a reflection of how lazy the banks had become.

Indeed, at the height of the property boom in 2017, UBS did a survey of borrowers who’d taken out a mortgage in the previous 12 months, which found one-third of applications were not ‘factual and accurate’. Having done a similar survey in 2015 and 2016, which reached roughly similar conclusions, they estimated the banks had about $500 billion of factually inaccurate loans on their books, which became known as ‘Liar Loans’ in the US during the GFC.

It’s blindingly obvious why things had to change.