A bear market opportunity

Winston Churchill’s admonition to never waste a good crisis is something all smart investors should keep in mind as financial markets wrestle with the potential for a recovery from the current bear market.

One opportunity not to waste is revisiting your weighting to Australian shares in an investment portfolio.

There is a well-recognised home country bias among investors all over the world, meaning most investors tend to be heavily overweight their own backyard, which is easy to understand given increased familiarity and ease of access.

For Australian investors two other factors have been important contributors to what Vanguard has previously estimated as an average of 73% allocation to domestic equities: the franking system which boosts dividend returns, and Australia’s economic record of avoiding recession for almost 30 years contributing to a perception of safety.

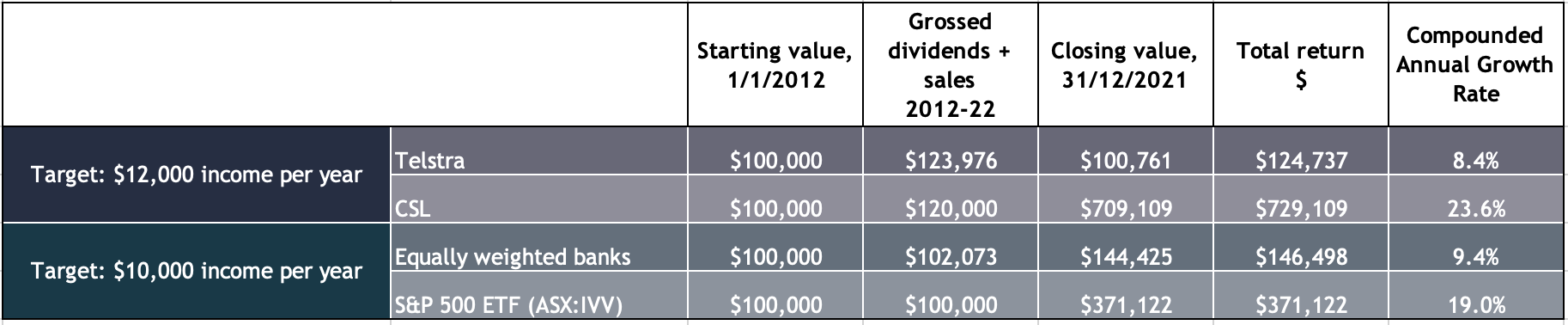

However, while franking credits are a terrific booster to returns, a better approach is to look at total returns from a portfolio, because it’s possible capital growth alone can far exceed the added return from dividends, especially in recovering markets.

And economic growth does not necessarily reflect in the share market, because its composition is very different to the broader economy, for example, the top 10 companies on the ASX 200 account for almost half the index, meaning it’s a heavily concentrated sample.

Harry Markowitz, one of the godfathers of modern portfolio theory, is famous for saying that diversification is the only free lunch in investing. Australia represents less than 3 per cent of global share market capitalisation, compared to the US being well over half and Europe around 20 per cent. This is where the opportunity lies.

Over the course of the current bear market, the drawdowns experienced by different countries have varied considerably. At the end of October, the ASX 200 was down 10 per cent from its highs, but the S&P 500 was off 20 per cent, the NASDAQ by 31 per cent, Europe 17 percent and the emerging markets 32 per cent.

There are many reasons behind that variability, but a big part of it is because this correction has especially impacted shares that were trading on higher PE ratios, which were often the more growth-oriented companies such as tech. Australia, and Europe for that matter, have a higher weighting to lower PE companies such as banks and resources.

This provides investors with the chance to take advantage of markets being on sale and rebalance portfolios to improve diversification by broadening what drives returns in the portfolio. For instance, at the company specific level, by the end of October there were household names that have no comparison in Australia that had been slashed from their recent highs: Nike was down by 48 per cent, Microsoft 33 per cent, Amazon 45 per cent, Disney 54 per cent, FedEx 49 per cent, Mercedes-Benz 32 per cent, Adidas 68 percent and Samsung 28 per cent.

It is entirely possible this correction is not over, and those names will get even cheaper, but trying to pick the bottom of a cycle is notoriously difficult, if not impossible. But there is no need to rebalance all in one hit, it can be done over time, in stages.

Likewise, at this point, it’s impossible to know which markets will perform best over the coming 10 years, but by spreading your bets you give yourself a better chance of avoiding the worst performing. For context, according to Vanguard, between 2010 and 2020, the Australian market returned 7.2 per cent per year, compared to the US market’s 15.9 per cent. Franking won’t double your returns.