The prospect of the U.S. Fed raising interest rates is frequently cited as one of the sources of volatility on global equities markets. The U.S. equivalent of our cash rate has been stuck at 0.25% for six years and the Fed has been telling us all year they want to raise it. Whilst it’s possible it could see a rise in volatility, higher interest rates does not necessarily mean lower share prices, in fact, going by history, it’s about 50/50.

Theory meets reality

Conventional wisdom says that when interest rates go up, asset prices should go down, including share prices. That’s because interest rates are central to valuing assets using a discounted cash flow method, and the higher the interest rate, the lower the current value of the asset. Another way to think about it is that when interest rates go up, the better return from interest bearing securities, like bonds, will attract some money out of shares.

So not surprisingly both equity and bond markets have been anxiously hanging on every utterance from the Fed looking for hints as to when rates will go up. But all the Fed has consistently said is they do want to raise rates but will be guided by the data. Why would the Fed raise interest rates? Because the data indicates economic growth and inflation are strong enough to require less support from monetary policy. And that’s where the theory can bump into reality: if growth and prices are that strong, it can be a very good environment for corporate earnings, which is positive for share prices.

What does history tell us?

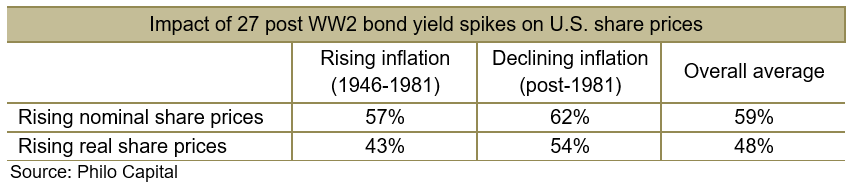

In a study of the 27 times U.S. bond yields have spiked upwards since WW2, Philo Capital found there was no consistent impact on share prices, whether or not inflation was rising or falling – see the table below:

Source: Philo Capital

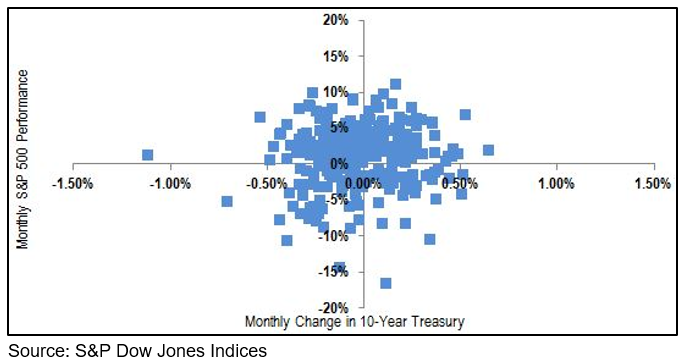

It works out at not far from a 50/50 chance that share prices will go up or down. This view was backed up in a study by S&P Dow Jones Indices, which found that rising bond yields don’t necessarily foretell the direction of equities – see the chart below.

Monthly changes in U.S. 10 year bond yields vs. monthly changes in the S&P500

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

When will the Fed lift rates?

Frankly, we have no idea and nor does anyone else, quite possibly including the Fed governors themselves. The next meeting is 17 September, and then December 16. Far more importantly is how sharply interest rates go up, and by all indications the Fed will be taking very careful note of how markets are affected, so they don’t upset them too much.

Interestingly, as one commentator pointed out when the Fed meets next week they will be looking at a US economy in which more people are employed than ever before, earning more money than ever before, producing more goods and services than ever before, and with personal consumption expenditures and corporate profits at the highest levels ever seen. Altogether that sounds like an economy that no longer needs record low interest rates.

So what should you do?

We have always maintained it’s next to impossible to time markets consistently and accurately. What you can do however is work out whether growth assets offer good value compared with being in cash or not. On our calculations the expected annualised return over the next ten years from equities markets makes them far more appealing than remaining in cash.

Whilst we’re not big fans of investment banking analysts, it was interesting to note Morgan Stanley said last week that all five market value indicators it monitors are showing a buy signal at the moment, something they call a “full house”. This only happens rarely and when it has equity markets have normally performed strongly over the next 12 months. Their main point is that equities are very cheap relative to bonds at the moment; in fact the trailing dividend yield on European stocks is 240bp higher than bonds, which is near its all-time highs over the past century. We would hasten to add that Morgan Stanley itself points out their model offers no insight on timing, but presciently there was a full house sell indicator at the top of the markets in June 2007.

Similarly, last week all seven indicators that comprise the CNN Money Fear and Greed indicator were at ‘extreme fear’, something that only happens very occasionally. Warren Buffet famously said “be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful”.

There are few certainties in life: death and taxes are two, and the Fed raising interest rates at some point is a third. What is not certain is what happens after that, but with equities markets having experienced such a sharp correction that is not based on unusual, structural reasons, it seems fair to say now is not the time to run with the fearful crowd.