In response to client questions, we recently posted part 1 of this article, which looked at the basics of what is meant when people refer to fixed income investing: the securities, what affects their price and how they differ from shares. In this second part we look at why bonds enjoyed a 30 year bull market that many experts forecast will come to an end but why this giant asset class still has a role to play in a typical Australian investor’s portfolio.

A 30 year bull market coming to an end?

Source: IRESS This chart shows the yield of the U.S. long bond. Remember, the higher the yield, the lower the price, so as the yield has declined over the past 30 years, the price has risen. An extraordinary 30 year bull market.

Anybody who had a mortgage back in the early 1980s will remember it as a time of high inflation that was eventually squashed by very high interest rates. We pointed out last week that one of the major influences on bond pricing is the outlook for inflation: the higher it is, the higher the interest rate you’ll require before buying the bond, meaning the lower the price is that you are willing to pay.

Not long after Paul Volcker was appointed as the Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve in 1979 inflation peaked at 13.5% p.a. Bond investors had been in a world of pain for almost 20 years as prices reacted to the mayhem of the oil shocks, but after Volcker pushed U.S. cash rates to a peak of 20% in 1981, inflation was smashed. It dropped to 3.2% by 1983 and so began a 30 year bull market for bonds (see the chart above) as investors became convinced that central banks had discovered the secret to keeping the inflation genie in the bottle.

We’re now seeing a world where sovereign bond yields are at or very close to all-time lows, numbers that on the face of them seem like a crazy annual return to accept in exchange for lending money to a government for ten years: the U.S. 1.82%, Japan 0.22%, Germany 0.35%, and if you want a Swiss bond you have to pay them 0.28% p.a. for the privilege! Not surprisingly, almost every bond fund manager argues yields simply cannot go a whole lot lower, which is another way of saying they expect the bull market will come to an end sooner rather than later.

Can you still make money from fixed income?

In short, yes you can. There are many different kinds of bonds, from government to corporate, and you can be pretty much assured that somewhere in the world there are attractive returns being offered. Proper fixed income investments are exactly that: you know in advance exactly what your return will be if you hold the investment to maturity. And if you stick to very safe investments, like sovereign bonds from a reliable debtor, then you can feel very comfortable you will get your money back together with the promised coupons.

But right now you’d think to yourself: hang on, if I buy a ten year bond from the U.S. I’m getting paid 1.8% p.a., which barely covers inflation. As with any investment, it’s a question of how much return you require and the risk you are prepared to take on to increase that return. There are other bonds offering more like 5-6% p.a. For some lucky investors they are happy just to know their money is safe. The other trick, as always, is being able to find them.

Also, there’s a concept in bond investing called ‘duration’, which measures a bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. You can deliberately target bonds that have lower sensitivity to interest rates, called lower duration, which means they will be less risky. The catch is, like all investments that are less risky, the offset is that they come with a lower return, being a lower interest rate.

Some fund managers are even able to make investments that benefit from rising interest rates, which is referred to as ‘going short duration’ (similar in concept to short selling shares – you sell them at a higher price and make a return by buying them back at a lower price).

Does fixed income have a role to play in an Australian investor’s portfolio?

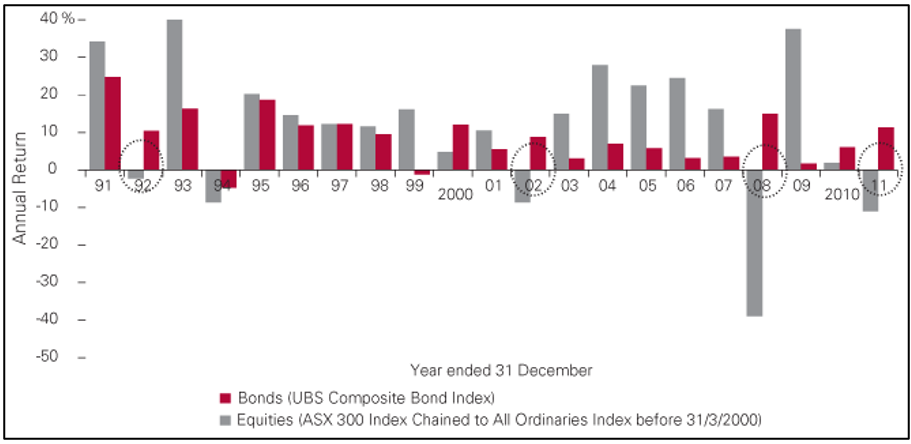

Definitely! One of the classic arguments in favour of all portfolios having at least some exposure to bonds is that they have a low, sometimes negative, correlation to equities. That is, when equities markets go down, bond markets can go up (see the chart below).

Calendar year returns for Australian equities and bonds

(from 31 December 1989 to 31 December 2011)

As we’ve argued many times, it’s next to impossible to predict on a short-term basis which asset classes will do well from one year to the next, but over the long-term you can confidently point to expected returns from particular asset classes. Having diversification in a portfolio is one of the simplest insurance policies you can get.

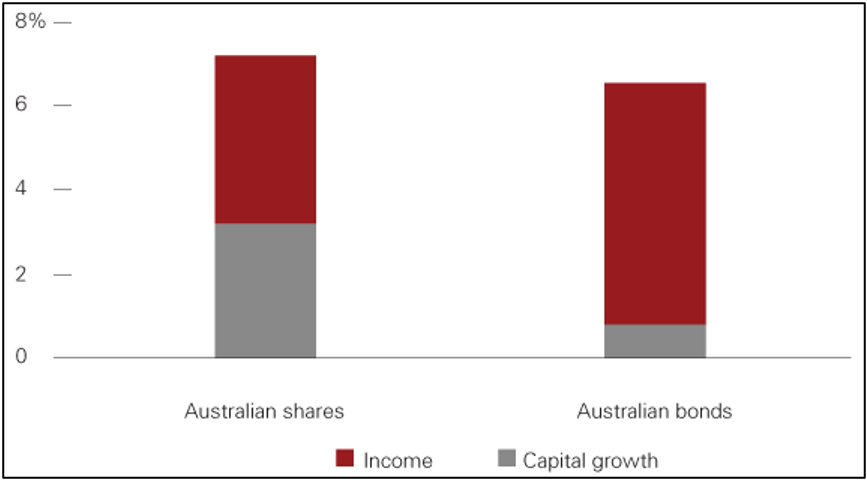

Another reason is that bonds pay a regular income stream, which for some investors can be exactly what is needed. The chart below shows the total return of bonds compared to shares over a 15 year period, and also shows how much of that return comes from income versus capital growth.

Components of total return 1997-2012

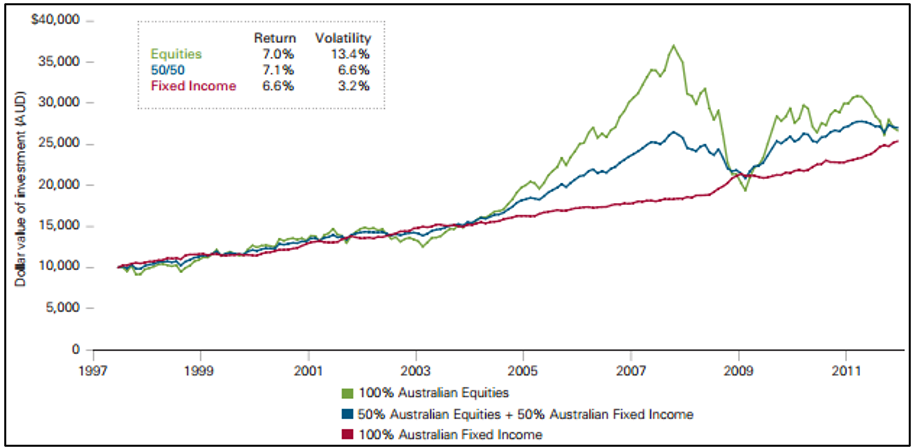

Finally, a portfolio with a blend of equities and bonds can see a reduction in volatility without severely impacting returns.

Asset class and portfolio investment performance

Source: S&P, UBS, Vanguard

Experts have been calling the end of the bond bull market now for several years and at some point they’ll be right. But given the sheer size of the asset class, the contribution it can make to portfolios and the variety of securities to invest in, it should not be ignored.