The stock market doldrums

Ancient sailors dreaded The Doldrums, a region near the equator whose atmospheric peculiarities would rob them of wind, leaving boats becalmed while the crew watched their supplies dwindle and cabin fever took hold. It took patience and faith that conditions would eventually improve, to see them through without doing anything they’d regret.

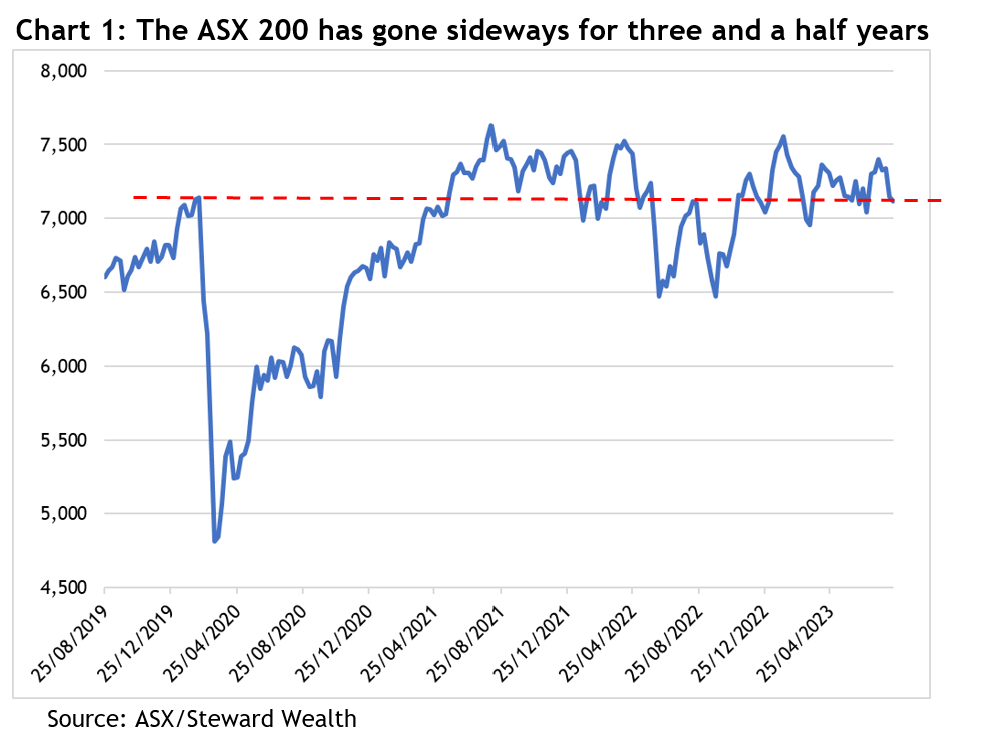

As the ASX 200 approaches the end of August, it is not only at the same level it was in May 2021, so two years in the doldrums, it’s also at the same level as immediately prior to the COVID correction of February 2020, that’s a full three and a half years of going sideways – see chart 1.

But as anyone who’s been invested over that time, and as the chart makes obvious, the Australian share market has been through some eye-popping gyrations in the meantime, enough to test the patience of plenty of investors.

It is no doubt frustrating that the ASX 200 has been trading in a 500 point, or 7 per cent, range for the better part of the last two and a half years and disheartening that the market appears to be in the grip of another correction after such a promising June and July, but a look at history gives some helpful perspective.

First, markets going sideways is not at all unusual. After the Australian All Ordinaries (the predecessor to the ASX 200) fell 25 per cent in the famous crash of October 1987, it took six and a half years to get back to a new high. Then after the horror of the GFC, the peak from late 2007 wasn’t revisited for almost 12 years. Despite those and a few other noticeable spells in the doldrums, over that 42-year period, the index has grown at a compound rate of 6.5 per cent per year, meaning investors will have (on average) doubled their money every 11 years.

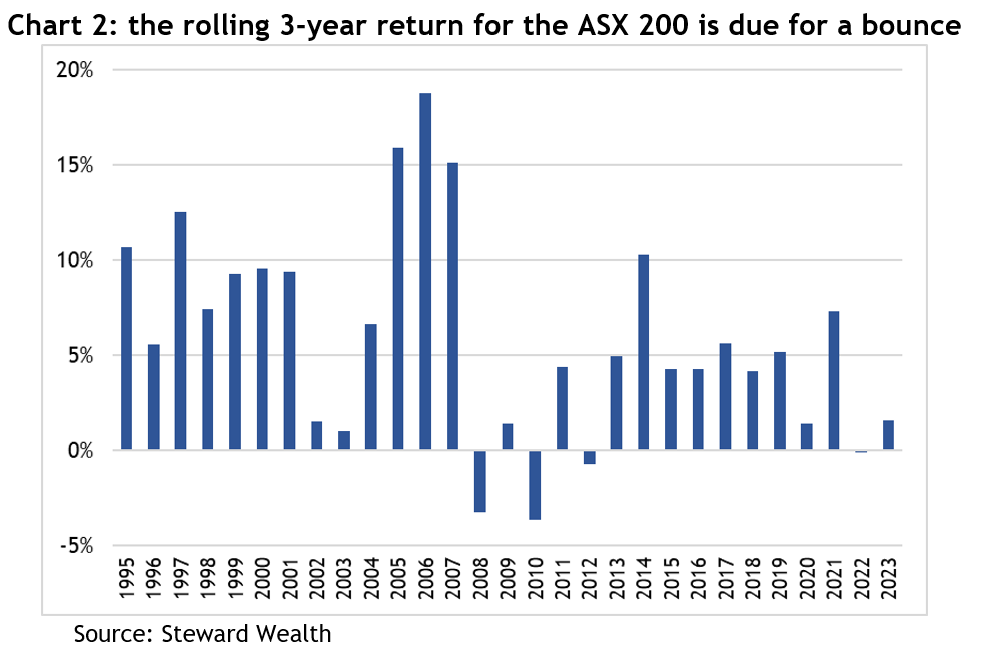

Second, if you look at the rolling three year returns over the past 30 years (so add the returns from 1993, 1994 and 1995 and divide by 3; then 1994, 1995 and 1996; and so on) the average has been a return of 5.9 per cent (which, coincidentally, is the same as the average annual return over the same period). The rolling three-year return to early August (well, not quite a full three years) has been 2.6 per cent, less than half the average, and it follows -0.1 per cent last year – see chart 2. In other words, while there are no guarantees about what will happen, history shows you can’t keep a good market down for ever.

As for the correction markets are going through, the volatility arrived bang on its seasonal schedule. The US Volatility Index, referred to as the VIX, normally goes through a gradual decline from 19 to 17 between January to July, then rises sharply to peak at 22 by the beginning of October – see chart 3.

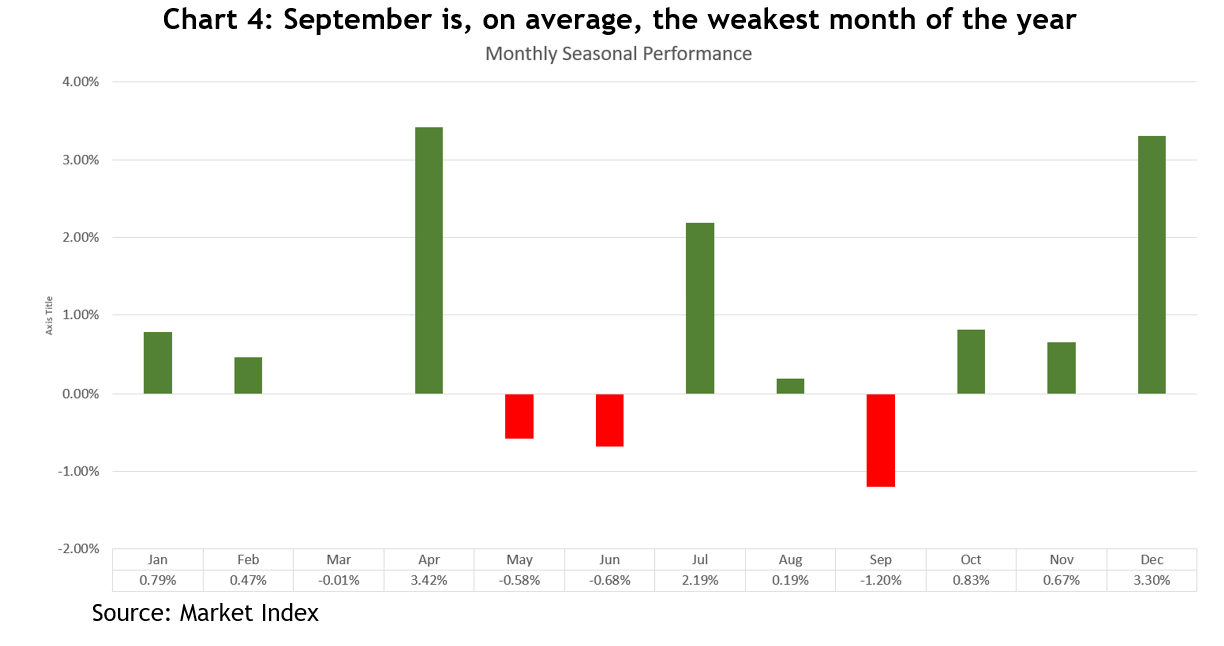

For the ASX, August is usually the fourth lowest monthly return, and we still have September to look forward to, which is the lowest – see chart 4.

Also, prior to the pullback, the US market had risen 19 per cent between mid-March to the end of July, without a serious pullback. The sheer weight of accumulated trading profits together with sentiment readings hitting extreme bullishness primed the market for a breather.

But even the pullbacks we’ve had this year have been a bit doldrumy. The biggest drawdown for the ASX 200 so far has been 8 per cent, back in March. Over the past 30 years, the average drawdown during a calendar year has been more than 12 per cent. That kind of volatility should be considered as part and parcel of investing.

Now for the silver linings. All those return statistics so far have ignored dividends. Over the past five financial years, the capital return from the Betashares A200 ETF (the cheapest ETF of the top 200 Australian shares available on the market), averaged 3.3 per cent per year. Adding dividends took that to 7.6 per cent, and franking credits made it a respectable 8.9 per cent. Dividends matter.

The other safeguard investors can take advantage of is portfolio diversification. Different parts of the world grow at different rates, for example, the State Street S&P 500 ETF (SPY), returned 17.8 per cent per year over the same five-year period, exactly double the ASX.

Similarly, an allocation to fixed income such as private credit, offered attractive yields of as much as eight per cent.

Share markets go up, down and sideways, but thankfully, over the longer-term, they invariably trend upwards. In times when markets are becalmed, smart investors should be like the ancient sailors: be patient and have faith, a tailwind will come along again.