For a long time Australian banks have been the cornerstone of many an individual investor’s share portfolio. And with good reason: over just the last four years their share prices have almost doubled, throw in generous fully franked dividend yields and the returns have been magnificent. However, the recent sharp correction in banks’ share prices reminds us that it is extremely rare that a particular share or sector is a one way bet.

Whilst we’re not suggesting the banks are facing an imminent collapse, we encourage investors to at least consider some of the relevant issues in forming your long-term expectations.

The chase for yield

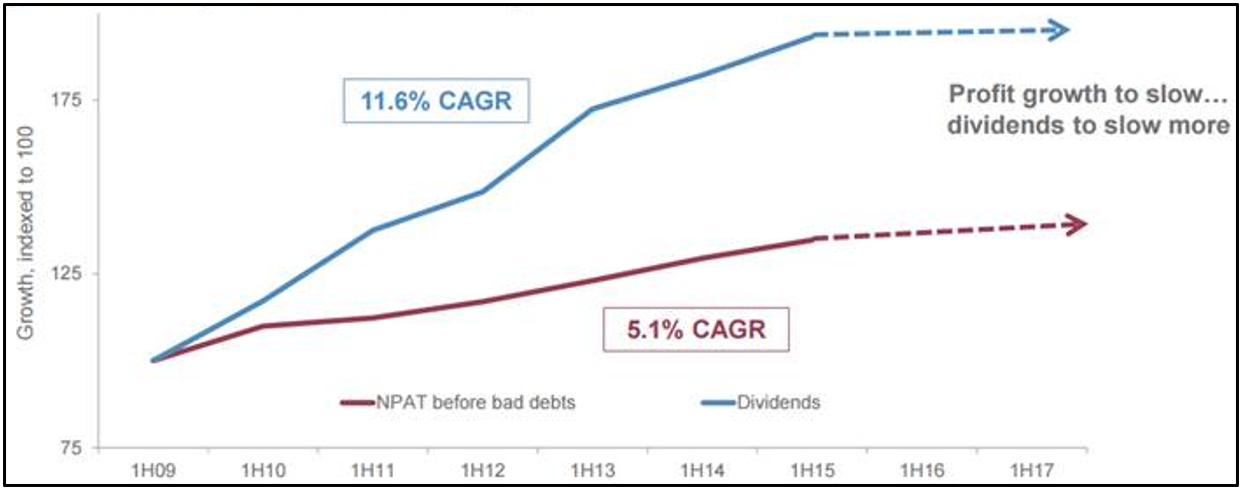

In the four years just after the GFC Australian bank profitability was very strong, which, together with some cyclical tailwinds, meant the amount of earnings paid out as dividends was able to increase strongly as well. With interest rates around the world at record lows, there was a global chase for higher yielding assets, and the Australian banks were prime candidates. The thing is, their dividend yields have been growing at more than double the rate of their underlying earnings (see chart 1 below), which is clearly unsustainable.

Chart 1: Big four banks: profit vs. dividend growth

Source: BT Investment Management

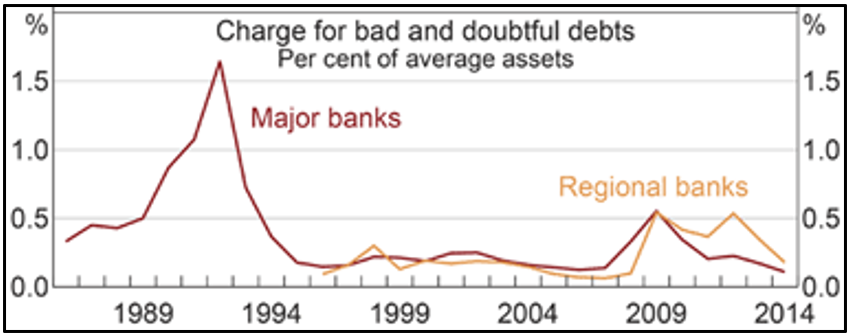

How have they managed that? A big part was a fall in their bad and doubtful debts provisions, which rose sharply during the GFC but are now at cyclical lows of about 0.2% as companies focused on reducing their debt and interest rates plunged – see chart 2 below.

Chart 2: Bad and doubtful charges at a cyclical low

Source: RBA

Bank profits: riding the household debt wave

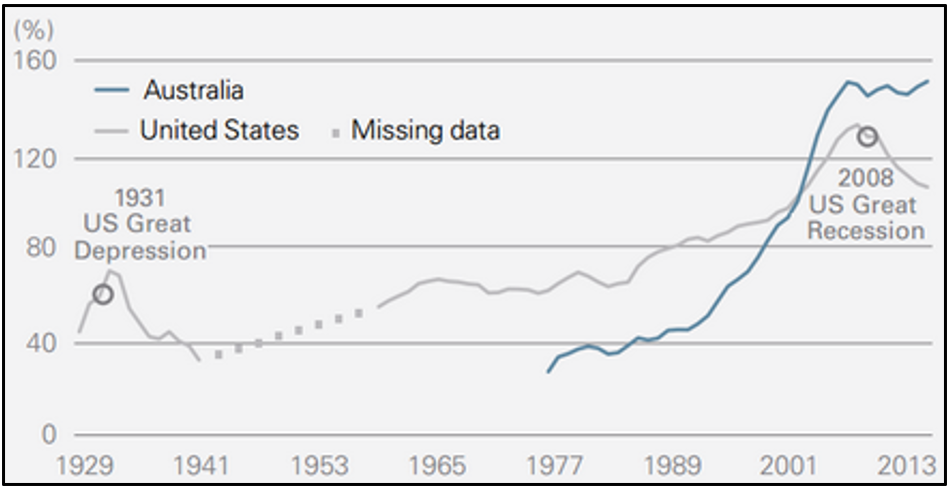

So how is it that banks have reported record profits when companies are pulling back on borrowing? A large part of it is because at the same time Australian households have increased their borrowing enormously to buy property, making them probably the most indebted in the world. In fact, since the 1950s, Australian credit has grown at five times the rate of GDP, again, a rate that is clearly unsustainable. Chart 3 below compares household indebtedness in Australia to the U.S. Two interesting things to note: we started off much more conservative than the U.S. and then rocketed past, and while U.S. households have de-geared after the GFC, Australians have not.

Chart 3: Australian household debt to income vs. the U.S.

Source: Merrill Lynch, Minack Advisers

It’s obviously disconcerting that bad and doubtful debts are at record lows when the Reserve Bank is warning that Australian property is getting expensive.

Banks: the 600lb gorilla of the Australian share market

The terrific rise in the share prices of the Australian banks has seen their weighting in the ASX200 increase dramatically, from less than 20% in late 2010 to a recent peak of more than 43%, and now 37% following the recent sell off – see chart 4 below.

Chart 4: Australian banks as a percentage of the ASX200

Source: IRESS

You could of course argue that this has just coincided with the decline in the fortunes of the resources stocks, which in 2008 accounted for 39% of the index and now are about 16%. But the point is, when a single sector becomes historically disproportionate in an overall index it usually turns out to be a cyclical phenomenon. Consider that technology, media and telcos made up 37% of the ASX200 in March 2000 (at the time News Corp was 14% of the index on its own!).

To put it in some international context, the Japanese banking sector accounted for just over 20% of the market at the peak of its debt and property bubble in 1990. Similarly, the U.K. banks were about 20% of the FTSE in the pre-GFC boom. The same thing underpinned the profitability of the banking sector in all three markets: rising debt levels.

In May all four of the major Australian banks were ranked in the top 14 globally by market capitalisation. Not a single French, German, Italian or domestic British bank was in that top 14, and there was only one Japanese bank (during its property boom Japanese banks made up nine of the top ten in the world!). These are remarkable statistics for a country with a population of 25m that represents only 2% of global GDP, and even more remarkable when you consider that the combined value of Australia’s big four banks is 20% more than the entire banking sector in Japan – the world’s third largest economy.

Why have the bank share prices fallen recently?

In the post-GFC regulatory environment banks all over the world have been under increasing pressure to improve their capital ratios, that is, the amount of equity the banks have on their balance sheets compared to the amount of loans they have. Underlying it all banks are pretty basic businesses: let’s say a bank takes in $100 of capital and splits that up into ten loans of $100, because the regulations say it only needs to keep 10% equity against each loan. If it charges an interest rate of 10% p.a. it’ll be getting a return on its $10 of equity per loan of 100% – a great business in anyone’s language. But if the regulations change and it now has to hold 20% equity against each loan, it either has to raise a heap of capital or cut back on the loans it writes. And the return on its equity will have halved to 50%. That will have a big negative effect on its share price.

That’s kind of what’s happening with the Australian banks. Over the past five years the amount of capital they have had to hold against domestic mortgages fell to about 15%. As that ratio declined, the return on equity rose. Then last year the Financial Services Inquiry (FSI) made two very important recommendations: the first is that mortgage risk weightings should double to 25-30%, and secondly, that Australian banks should have “unquestionably strong” capital ratios compared to their global peers with a baseline target being mid-top quartile.

The local regulator, APRA, has started to raise the mortgage risk ratios. They’ve not been clear on the second recommendation, but it will come as a potentially rude shock to many Australian investors accustomed to thinking our banks are amongst the best capitalised in the world, having made it through the GFC relatively unscathed, that in fact they rank in about the middle of the second quartile globally for tier one equity levels.

Overall that means the Australian banks have a lot of capital to raise. Exactly how much is not clear, but estimates range from $60-100bn over the next four years if they are required to have a 10% tier one capital ratio. Much of that is expected to come from retained earnings (which will put downward pressure on dividend payout ratios) with some from capital raisings, which is already happening. We’ve seen National Australia Bank do a $5.5bn capital raising (partly to support their U.K. operations), Westpac raised a small amount with the sell down of some of its equity in BT Investment Management and just last week ANZ announced a $2.5bn capital raising. Obviously that leaves Commonwealth Bank.

Where does that leave you?

Overall APRA’s capital requirements are not a big hurdle for the banks, but we saw with ANZ’s 8% fall last week that the market is wary. But that’s perhaps more of a short-term consideration. The bigger question may well be whether it’s realistic that the banking sector represents such a high proportion of the overall index. It’s also worth bearing in mind that if you own a house as well as bank shares, you’re effectively doubling your exposure.

Our asset allocation consultant, farrelly’s, forecasts a ten year annualised return for the Australian banks of 11.2%. Remember, that won’t go in a straight line, inevitably there will be some years that are much better than others.

Like everything in investing, it boils down to how comfortable you are with the balances of your portfolio. If you have a disproportionately large exposure to the banking sector, you should consider taking advantage of the one of the most basic rules of risk management: diversify.

As we said at the start, we’re not forecasting an imminent collapse of banks’ share prices, but sometimes it pays to stop and ask: does that make sense? And if it doesn’t then make sure you’re not overly exposed