With inflation once again taking centre stage in the financial media, speculation is rife that central banks will have to respond. Conventional wisdom says the way to do that is to raise interest rates, the theory being that it moderates demand which feeds through to reduced prices. This playbook comes largely from how the US Federal Reserve dealt with the worst inflationary period of the modern era, at the end of the 1970s.

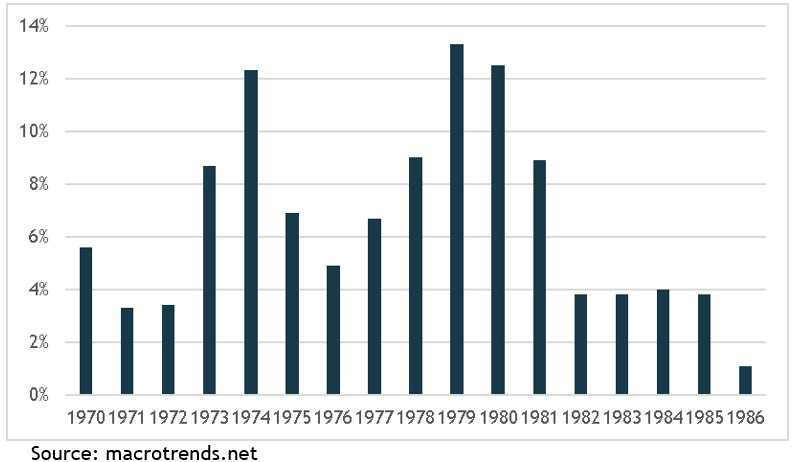

The narrative is that “Tall Paul” Volcker, the US Fed Chairman who stood 6’8”, crushed the US’s 14% inflation rate of 1980 by driving interest rates to a record high of 20%, throwing the economy into a savage recession. While he became one of the most hated men in America, by 1982 inflation averaged just 3.8% for the year. The message was clear: raising interest rates kills inflation.

Or does it? If interest rates are that powerful, how come central banks failed to increase inflation by keeping them super low for the past 10 years? There is an alternative view about inflation that begins with the premise that modern economies are incredibly complex; so complex in fact that to suggest using one single tool, the overnight cash rate, to control it is fanciful. To explore this view, it helps to have some context: a quick overview of the 1970s oil crisis.

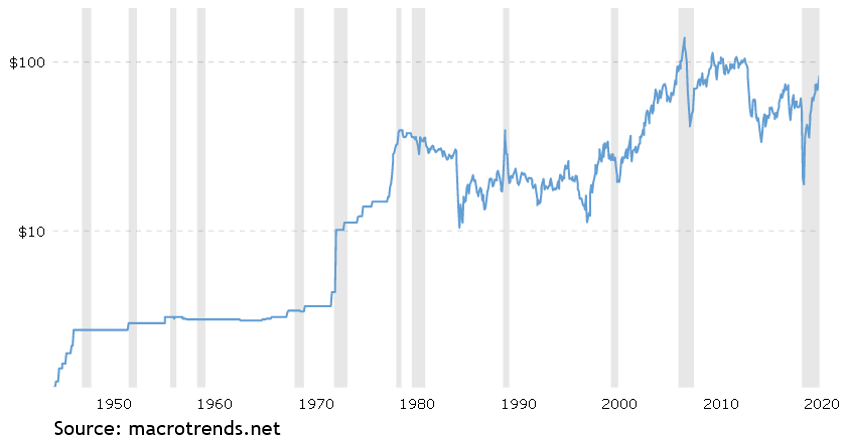

Crude oil prices (log scale)

In the 1960s the US was largely self-sufficient for oil, and prices were kept super stable by the Texas Railroad Commission setting quotas. However, in October 1973, when the US was more dependent on foreign oil than it had ever been, especially from Saudi Arabia, OPEC declared an oil embargo against those countries that had supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The oil price just about tripled from US$3.60 per barrel to more than US$10 per barrel only six months later.

Oil, of course, is completely woven into modern economies, from transport, to energy production, to forming critical components of an almost endless list of manufactured products. Prices started to rise across almost all goods as producers passed on the higher input costs at each stage of production, and US inflation rates went with them, rising from an annual rate of 3.4% in 1972, to 8.7% in 1973, to 12.3% in 1974.

US annual inflation rate

By the time Jimmy Carter was elected president in 1976, oil was trading at $13.90 per barrel and US oil imports had shot up 65% annually since 1973 to be 48% of total consumption. In 1976 the nation was consuming one-quarter of all of OPEC’s production and was woefully wasteful in its energy use, with consumption per capita 2.3 times the average for nations in the European Economic Community and 2.6 times Japan’s.

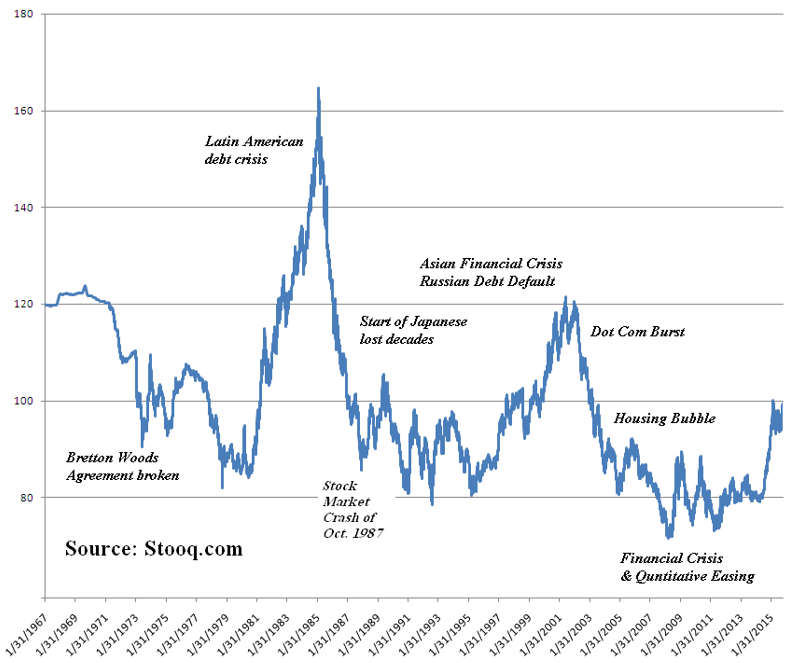

Adding to the general inflationary pressures was the US$ index (DXY, which is a weighted measure of the US$ against its major trading partners) fell from 115 in 1971 to 80 in 1977 after the US abandoned the gold standard. That meant all imports cost 30% more over that six-year period, on top of the oil price rise.

US DOLLAR INDEX 1967-2015

Then in 1978 the Iranian revolution prompted a strike at the nationalized oil refinery, reducing production from 6 million barrels per day to 1.5 million. While that only represented about 4% of global supply, the oil price jumped again to $39.50 by 1980. All told, the oil price had risen 1000% in seven years and the inflation rate hit a post-war high in 1979.

What followed, however, was a classic combination of market and regulatory responses that brought about a remarkable reversal in oil prices thanks to tectonic shifts in both supply and demand.

In 1978, Carter deregulated oil and gas prices, which prompted an increase in oil exploration and led to a huge increase in the domestic supply of energy over the following years. By the time Carter left office in 1980, foreign oil had fallen to be 40% of US consumption, a reduction equivalent to 1.8 million barrels per day, oil inventories had risen sharply and there was a surplus of gas. Then between 1980 and 1985, domestic US production increased by almost 1 million barrels a day, while imports of crude oil and petroleum products declined from 8.2 to 4.5 million barrels a day.

On the demand side, automobile fuel economy standards were introduced in 1975 that required a doubling of efficiency by 1985, and stories abounded of households yanking out their old oil burning heaters to switch to gas, which was in surplus. All in all, by 1986 the oil price had fallen more than 70% to $10.40 per barrel, aided in part by a resurgent US$ that doubled in value between 1980 to 1985.

Not surprisingly, the alternative view about how the record level of inflation in the 1970s was crushed by the mid-1980s revolves around the real world effects of a huge rise in the most critical commodity, followed by a huge decline.

While suggesting the single act of raising interest rates solved the inflation problem is an appealingly simple solution, and it may indeed have contributed, when you account for the incredible complexity of a modern economy, it shouldn’t be surprising there would be a lot more to it. Not all price increases are going to be effectively resolved by increasing the cost of money.

Professor Stephanie Kelton of Stonybrook University, a recognised advocate of MMT, puts it this way: if the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) was to be struck down, depriving many people of health insurance and allowing insurers to price based on pre-existing conditions, it’s estimated health insurance premiums would rise by up to 30%. If that happened, it would show up in the inflation numbers. How would raising interest rates reduce that kind of inflation? Reducing people’s access to money or credit won’t drive down health costs. However, regulating the cost of health insurance would, or the cost of drugs and medical care.

In the context of our current elevated rate of inflation, much has been made of the 10-fold rise in the cost of shipping containers. Already though, there are ways that is being addressed:

- The port of Los Angeles recently allowed containers to be stacked four high instead of two, freeing up space for ships to empty their cargo

- Up to 70% of container space is fresh air and new software packages using AI are available to guide companies on the most efficient way to pack their goods

- Astonishingly, container contracts are currently unenforceable, simply changing that would increase certainty for companies

- There is a website being developed to establish a ‘secondary market’ so that companies that have spare container space can put it on the market

These are practical ways of reducing pricing pressures that simply raising interest rates, which can only change the price of money, could not achieve.

The conventional view that the way to fight inflation is by central banks increasing interest rates arguably stems from a misinterpretation of correlation and causation dating back to the 1980s. Interest rates undoubtedly have a role to play in managing a modern economy, especially with respect to house prices where a high proportion of transactions rely on borrowing money. As for the rest of this very complex economy, a better approach could be to see them as part of the solution.