A young couple asked us recently for advice on whether they should invest their $400,000 of savings into an investment property or a share portfolio. Like the old days of Holden versus Ford, that’s precisely the question that can divide your typical Australian barbecue crowd.

Both asset classes have rewarded investors handsomely over the years, but just like knowing the differences between a Holden LS3 V8 and a Ford Miami Supercharged, there are nuances that can make a huge difference to a smart investor’s choice.

The basics

There are some obvious differences between investing in shares compared to property, like transaction costs, where stamp duty and conveyancing fees can add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the cost of a property.

Holding costs are also significant, such as paying a property manager’s fees to look after rent and maintenance, the dreaded property taxes, rates, and insurances, none of which apply to a share portfolio.

Then there’s liquidity. Firstly, it can take months to find and settle on a property, then if you want to sell it, it can take months all over again. Secondly, if you need to raise some money, you can’t just hive off a bedroom and sell that. With a share portfolio, you can sell as much or as little as you need, and you’ll have the money in your bank account three days later.

Compounding and reinvesting

One of the first lessons of investing is to make the most of the “magic of compounding”, where you get returns on top of your accumulated returns. Allow those returns to run for years and bingo, it’s like magic.

Where things get more interesting is if you can accelerate the compounding effect by reinvesting the income the investment generates.

For example, when shares pay a dividend, you can reinvest that money back into the shares, so you have more shares, and next year you’ll get an even bigger dividend on your larger shareholding – and so on.

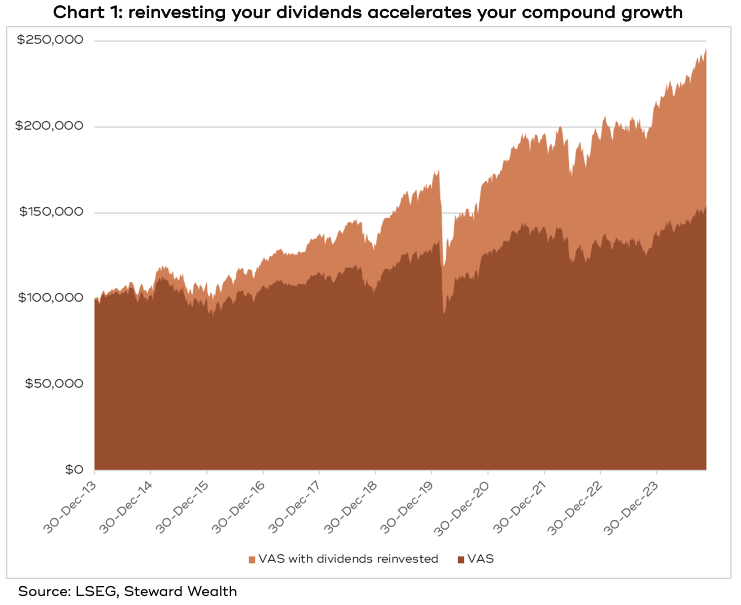

The Vanguard Australian Shares ETF (VAS) has returned 4.1 per cent per year since the start of 2014, so $100,000 invested back then was worth more than $154,000 by mid-November this year.

Along the way though, it’s paid an average of 4.5 per cent per year in dividends and if you’d simply ticked the box to reinvest those dividends, your investment would now be worth more than $246,000. Chart 1 shows the difference dividend reinvestment makes.

You could also have chosen to invest into an ASX-listed ETF of the S&P 500, like IVV, where $100,000 invested 10 years ago would have been worth $441,000 by mid-November, and with dividend reinvestment, $521,000, a whopping 16.3 per cent per year.

A portfolio equally split between those two ETFs would have returned 13.7 per cent per year, and taken your $100,000 to $404,000.

There’s no real way to reinvest your rental income into an investment property. You can put it toward enhancements, like painting or new fixtures and fittings, but there’s no assurance of extra return, or you can pay off the loan, but that will reduce the return on equity.

Franking credits

Negative gearing is usually the most talked about tax advantage of investing in property, which enables you to claim a tax deduction for the difference between what it costs to hold a property and the income it generates.

With interest rates where they are, a lot of those costs are interest. However, as you pay down the loan or rates fall, the amount deductible for negative gearing goes down, which is not altogether a bad thing, because remember, a loan will still carry a non-claimable cost.

Something not appreciated by a lot of investors is that you can usually claim a tax deduction for interest on loans taken out to invest in a share portfolio, whether that’s through a margin loan, which is specifically designed for investing in shares, or through a bank loan, perhaps secured against your home.

Additionally, Australian shares can come with franking credits, which reduces the tax payable on the dividends, and as the dividend stream grows, so too will the franking credits, whereas there are no franking credits associated with an investment property.

For the VAS portfolio, over the 10 years to 2024 the franking credits added an extra 1.5% per year, bringing the total return to 10.1 per cent.

Concentration risk

Buying an investment property means you have a lot of money tied up in a single asset, which is called concentration risk, and if you pick the wrong area, or street, or house, the returns may not be so good (the opposite holds true as well).

Whilst SQM Research reckons the price for a three-bedroom Australian house has risen by 6.4% per year over the past 10 years, you can’t just buy a ‘typical’ one.

An advantage of shares is that if you want to avoid concentration risk you can buy the whole market, and that market can be Australia, the US, Europe, Japan, or a bit of

each. Or the huge variety of ETFs available means you can buy a bunch of companies in one hit that are associated with a particular theme, like cybersecurity, robotics, or,indeed, property trusts.

What’s more, if you have a bit of extra cash, you can easily buy some more shares, to add to that all important compounding effect, whereas again, you can’t just buy a bit

more of your investment property.

Capital growth

We’ve all got stories of our grandparents who bought a house for $200,000 50 years ago and just sold it for $2 million. Those kinds of numbers are a great argument for buying property.

But despite being a 10-fold increase in value, the annualised return for grandma was less than 5 per cent per year. And that doesn’t take into account the costs of owning a home along the way (though don’t for a moment think we would not recommend buying a home to live in, which is the most tax effective investment you can make).

Whenever we work out the net rental yield on a client’s residential investment property (the amount of rental income after all costs divided by the value of the property), it usually works out to be less than what you can get on a risk-free term deposit in a bank. By definition, that makes it a speculative investment, meaning the only way you can justify holding it is to make a capital gain.

Gearing

Much of the gains people make on property is a combination of borrowing a heap of money to buy it and hanging on for years.

If you’d bought a property for $1 million 10 years ago and contributed $200,000 of your own money, then it would have been geared at 80%. If the property value increased at 6.4 per cent, it would now be worth $1.860 million. Let’s say your loan is still sitting at $800,000, your share of the property value, which is called your equity, has grown to $1.060 million, which means the return on your equity was 18.1 per cent per year – almost three times the value of the property. That is a fabulous return.

You can, of course, get the same gearing effect with shares, as chart 2 shows.

We’ve already seen investing in a portfolio equally split between VAS and IVV, and reinvesting the dividends, earned an annual return of 13.7 per cent over the 10 years to 2024.

Let’s say you invest the same $200,000 of your own money, together with a loan of $100,000, into the same 50/50 VAS/IVV portfolio. The total investment would be worth $300,000, of which one-third is debt, so the portfolio is 33% geared (to reduce complexity, I’m assuming the portfolio’s dividends are reinvested and the loan costs paid out of other income).

After 10 years, the portfolio would have been worth around $1.083 million. If you’d not reduced the loan at all, then your share of the portfolio (i.e. your equity), has grown from $200,000 to $983,000, a return on your equity of 17.3 per cent per year.

However, if you were willing to gear to 50 per cent, that is, put in $200,000 of your own money and borrow $200,000 for a total investment of $400,000 (still only one quarter of the amount borrowed for the investment property), just your equity portion would now be worth $1.244 million, a return of 20.1 per cent per year.

That’s the magic of gearing, but the magic can be miserable if either your property or share portfolio goes down, then you are geared the opposite way.

Risk

A lot of investors are put off shares because they’ve heard the horror stories of share markets crashing, and that volatility is equated to risk.

It’s absolutely correct that share markets are more volatile than property, but that’s because of liquidity. Shares are priced on a second-by-second basis, five days a week, whereas your average investment property gets valued maybe once a year.

If you were to take offers on a property every day, you could easily see changes of $100,000 either way. The volatility is just masked by the illiquidity.

Liquidity can be a blessing and a curse. A blessing because if you need to raise money you can sell shares on the ASX and the money will be in your bank account three days later. A curse because if you get caught up in a market panic, it’s all too easy to press the sell button.

There is no doubt investing in property can be very rewarding, especially for those who don’t mind borrowing and have time up their sleeve, plus there are some people who are just not cut out to invest in shares. But when you account for liquidity, diversification, tax and costs, shares do stack up well.