Is the AI trade a bubble? It’s the question dominating headlines right now. At our recent Investment Committee meeting we put the issue under the microscope, trying to separate narrative from numbers: on one side sit eye-watering capex plans, concentration risk and pockets of froth; on the other, the world’s most profitable companies, cash-funded investment and tangible earnings growth.

What follows sets out both cases—why the current surge could be classic late-cycle exuberance, and why it could instead be the early innings of a long, productivity-driven build-out—along with the signposts we’re watching and what this balance of risks means for portfolios.

ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR OF A BUBBLE

Right now, it seems the US financial markets are dominated by AI, especially the share market. J.P.Morgan pointed out that over period from the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 to the end of September this year, AI related stocks accounted for 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth and 90% of capital spending growth.

There is a race between the so-called AI hyperscalers, companies like Meta, Amazon, Google and Microsoft, to be the dominant player in the space, which requires building sufficient data processing capacity to handle the potentially billions of queries per hour. That processing is done in data centres, or more specifically, AI factories (a data centre might host a website or provide cloud storage for data, whereas an AI factory is dedicated just to AI).

Giant numbers

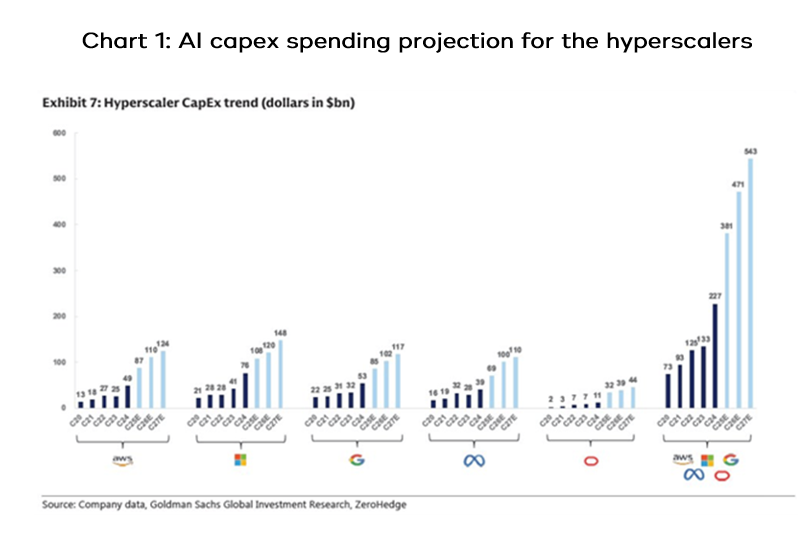

Projections of the amount of money that will be spent by the AI hyperscalers to build out the infrastructure are otherworldly: Goldman Sachs forecasts they will be spending more than US$540 billion per year by 2027, while McKinsey estimates total spending will reach US$5.2 trillion over the next five years – see chart 1.

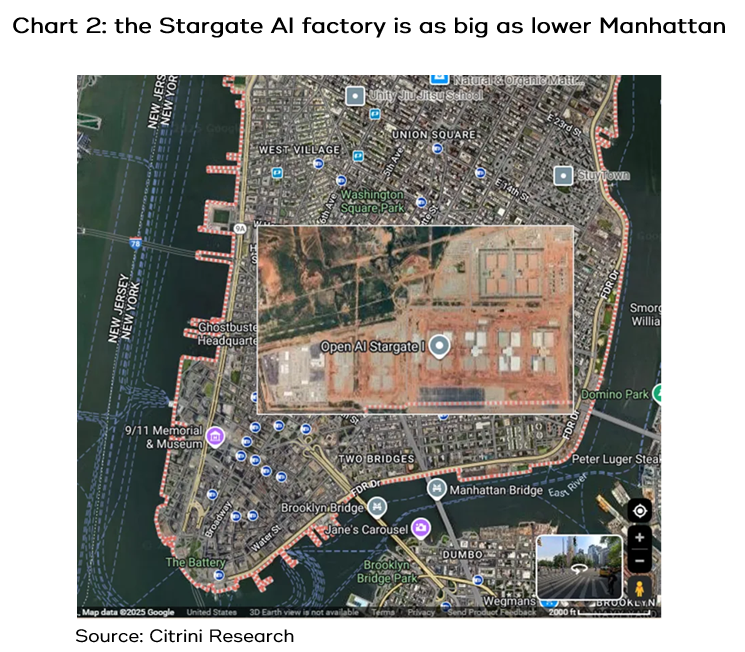

The scale of construction being undertaken by these companies is hard to fathom. One AI factory, being built by OpenAI (which owns ChatGPT), is called Stargate, in Texas. The site is as big as 600 football fields, or about the same size as lower Manhattan – see chart 2.

It is designed to eventually consume 1.8GW of power (the Yallourn coal fired power station generates 1.5GW and provides 22% of Victoria’s power), with 12 buildings totalling 6 million square feet of space, each holding 100,000 GPU chips (the ones made by Nvidia that power AI). The cost: US$500 billion over four years.

But wait for it: there are seven other AI factories slated for construction in the US, some of them bigger than Stargate!

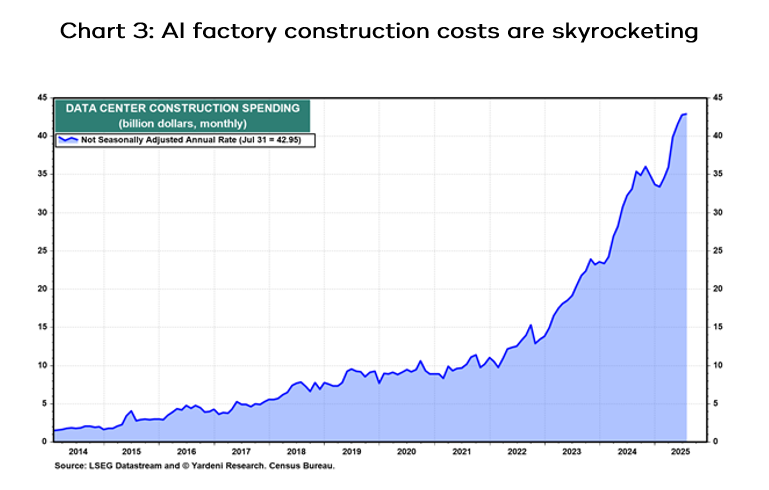

The scale of demand, quite predictably, is sending AI factory construction costs skyrocketing, with the average cost rising from $665 per square foot in August 2024 to $977 by August this year, an increase of 47% in one year – see chart 3.

Circular funding

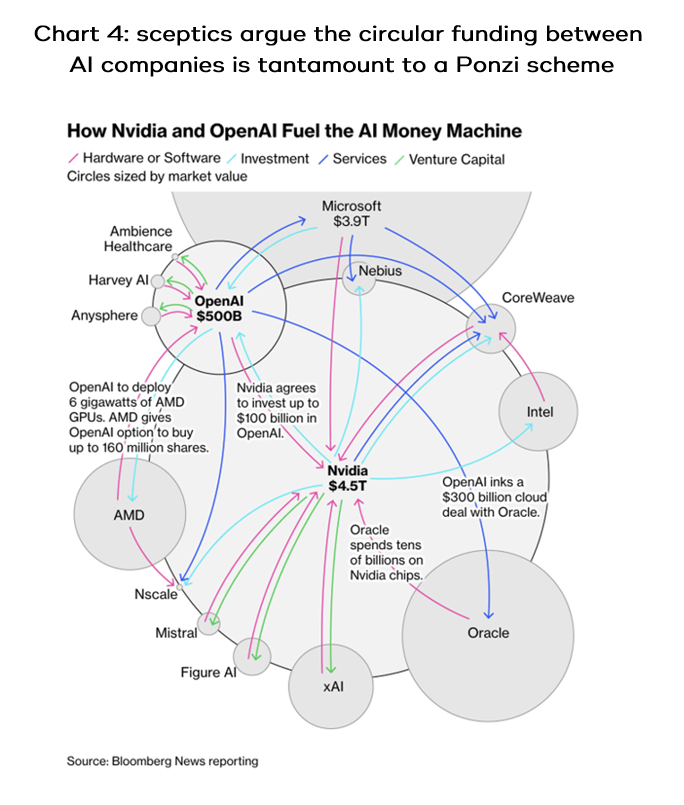

Another source of concern is the apparently circular funding that’s going on in AI. For example, Nvidia, which supplies most of the chips used in AI, announced a US$100 billion investment in OpenAI (the owner of ChatGPT), and OpenAI announced it was investing US$100 billion into Nvidia chips. Sceptics argue the dozens of similar deals that have been announced between the various players in the AI space amount to not much more than a Ponzi scheme – see chart 4.

Stretched valuations

The market has sometimes shown surprising levels of enthusiasm for these deals. For example, Oracle’s stock jumped by 25% after being promised US$60 billion a year from OpenAI. But as J.P.Morgan pointed out, it’s an amount of money OpenAI doesn’t earn yet, to provide cloud computing facilities that Oracle hasn’t built yet, and which will require 4.5 GW of power (the equivalent of 2.25 Hoover Dams or four nuclear plants), as well as increased borrowing by Oracle whose debt to equity ratio is already 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft and even less at Meta and Google.

Likewise, there are relatively newly minted companies involved in the AI buildout trading on valuations that appear to be factoring in heroic assumptions about their likelihood of success. For example, OpenAI, which is still in private hands, recently raised capital that valued the business at US$500 billion.

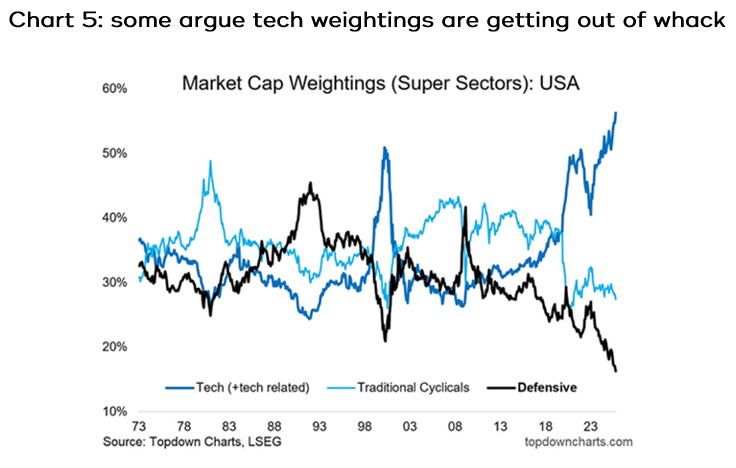

The upshot of the listed tech stocks’ incredible rally over the past 10+ years is that their weighting in the US stock indices, like the S&P 500, has grown to a level that some seasoned observers describe as out of whack, itself reflecting a level of irrational exuberance, or possibly hidden opportunities in the neglected sectors – see chart 5.

Hand in hand with the growth in tech stocks’ collective market capitalization, is the risk of stretched valuations. It’s one thing for a company to trade on a high price to earnings (PE) ratio, where the earnings are after tax and costs, but when stocks are trading on a high multiple of sales, that presents a new level of risk, because it doesn’t account for the costs of running the business. Chart 6 shows the total market capitalization of names in the S&P 500 that are trading at more than 10 times sales is at multi-decade highs.

Echoes of the dotcom boom

There is an abundance of comparisons of today’s market to the dotcom boom that popped spectacularly in early 2000. Just like AI, the dotcom episode revolved around a new technology (the internet) that promised far reaching transformation of business and day-to-day life, plus companies were spending spectacular amounts of money building the required infrastructure.

By the time the share market fell, the biggest players had spent an estimated US$500 billion on laying fibre optic cables, 85% of which went almost unused for the next 10 years. Eventually the cables ran at full capacity and made huge contributions to both affordable accessibility and broader economic activity, but by that time the companies that laid them had gone bust.

ARGUMENTS AGAINST A BUBBLE

Real companies with real earnings

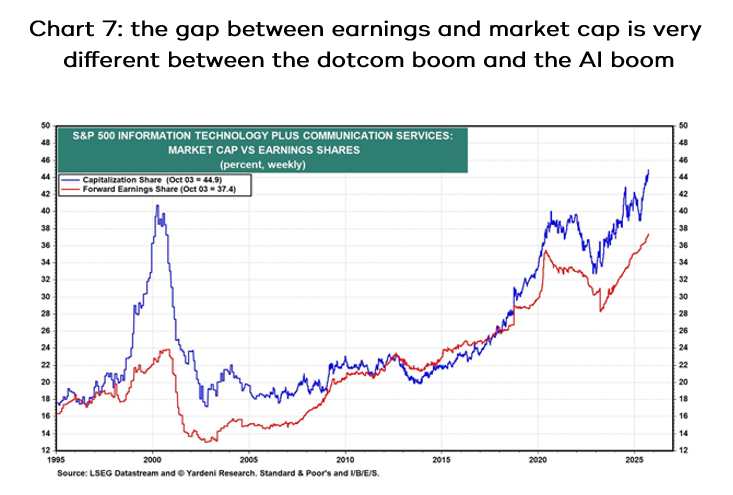

There is a huge and critical difference between the dotcom bubble and the current market: today’s market darlings are the biggest, most profitable and well capitalised companies in the world, and each runs a real business that generates mountains of real earnings and free cash flow. Chart 7 shows the gap between the tech companies’ market cap and their earnings back in the dotcom boom compared to today.

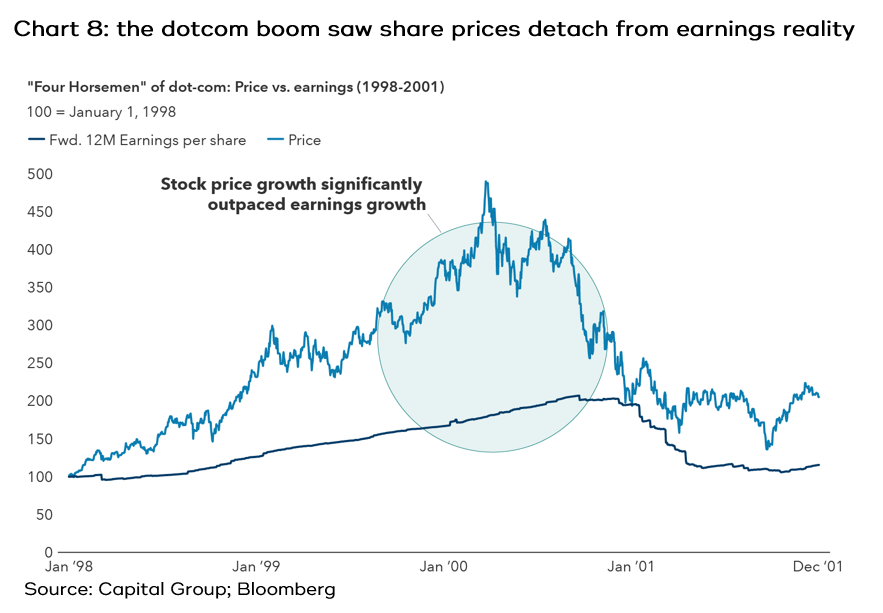

Charts 8 and 9 show another way of looking at it. Chart 8 shows how the share prices of four of the largest companies of the dotcom boom, Cisco, Dell, Microsoft and Intel, became completely detached from their earnings reality.

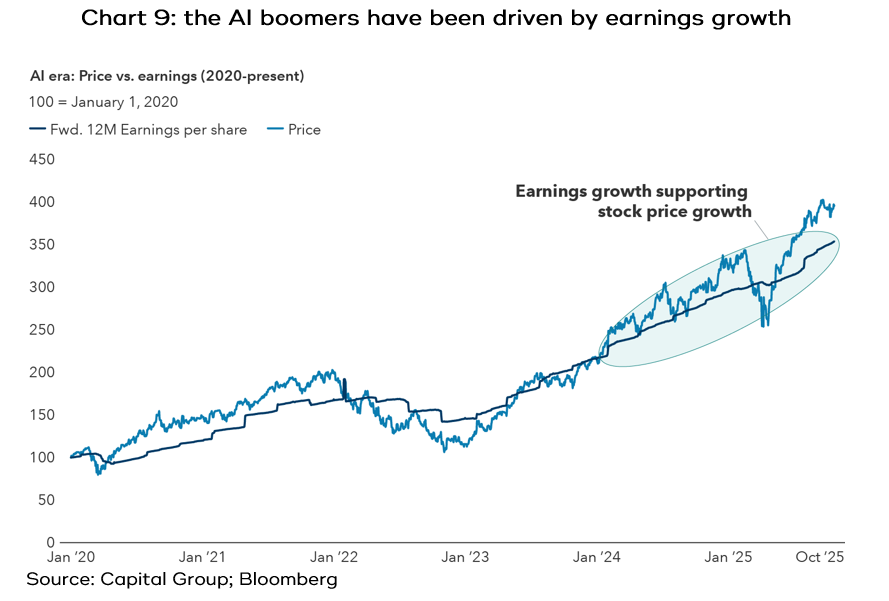

Whereas chart 9 shows how the biggest AI boom companies, in this case Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Broadcom, Meta and Amazon, have clearly been driven by their earnings.

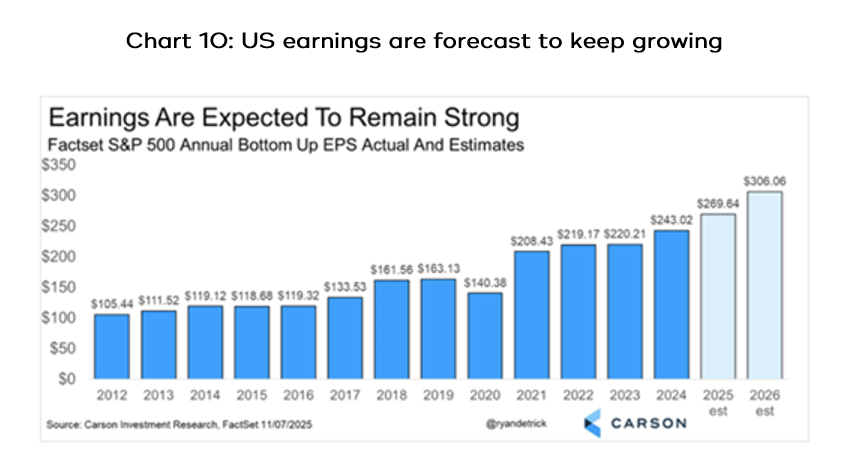

So what’s the outlook for earnings growth? US companies have just reported third quarter earnings. Going into the reporting season, analysts were forecasting 8% earnings growth year on year, but it ended up being 13%, that’s a significant positive surprise. For the full 2025 calendar year, current forecasts are for 11% growth and for 2026 it’s 13.5% – see chart 10.

How sustainable is the capex boom?

An important driver of the US share market is that the money being spent on AI capex isn’t just being reflected in the share prices of the AI hyperscalers. Those hundreds of billions of dollars are like a massive fiscal injection (like we saw from governments during COVID), and they flow to all kinds of companies and sectors that are providing goods and services to the AI factories, like the earth moving gear that prepares the sites, the steel that goes into the buildings, and the heating and ventilation companies that keep them cooled.

For example, Caterpillar (yellow gear, like bulldozers) shares are up by more than 50% year to date, GE Vernova (energy) is up more than 80% and Siemens (power) by more than 25%.

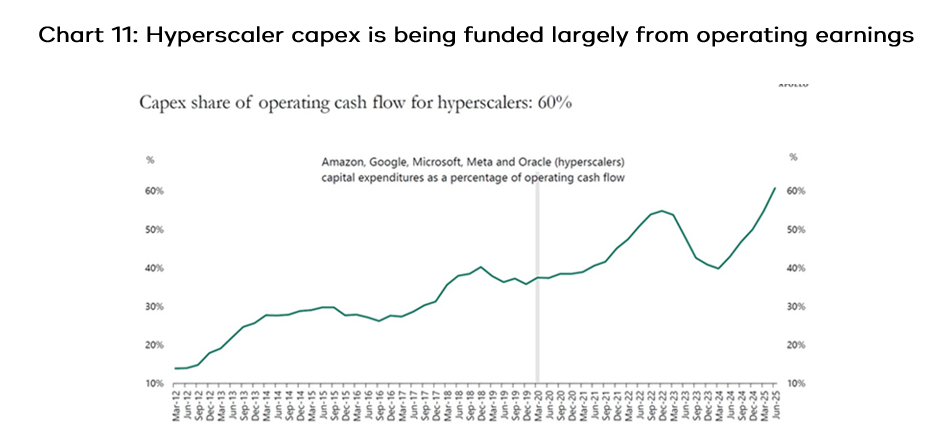

So, how sustainable is the capex spending? Critically, to date the money being spent on capex by the hyperscalers is being funded largely from operating cashflows – see chart 11.

As for the sustainability of the capital spending, clearly it can’t go on at the current rate of growth, however, comments from some of the CEOs indicate they’re in it for the long run:

- Mark Zuckerberg (Meta): If we end up misspending a couple of hundred billion dollars, I think that that is going to be very unfortunate, obviously. But what I’d say is I actually think the risk is higher on the other side.

- Sam Altman (OpenAI): the company is prepared to invest trillions of dollars over time in artificial intelligence infrastructure.

- Larry Page (Google): I’m willing to go bankrupt rather than lose this race.

As yet, the biggest companies in the world have yet to meaningfully tap their balance sheets to support their AI spending programs, which means there could be quite a way to go.

While debt levels are rising, importantly, most of it is not bank debt, which reduces the risk to the broader economy should things go pear-shaped, because banks won’t be forced to stop providing credit.

Timing

Firstly, there’s no set rules for determining if the market’s in a bubble or not. To date earnings have been rising, so if there are fundamentals behind the rising share price, can it be a bubble?

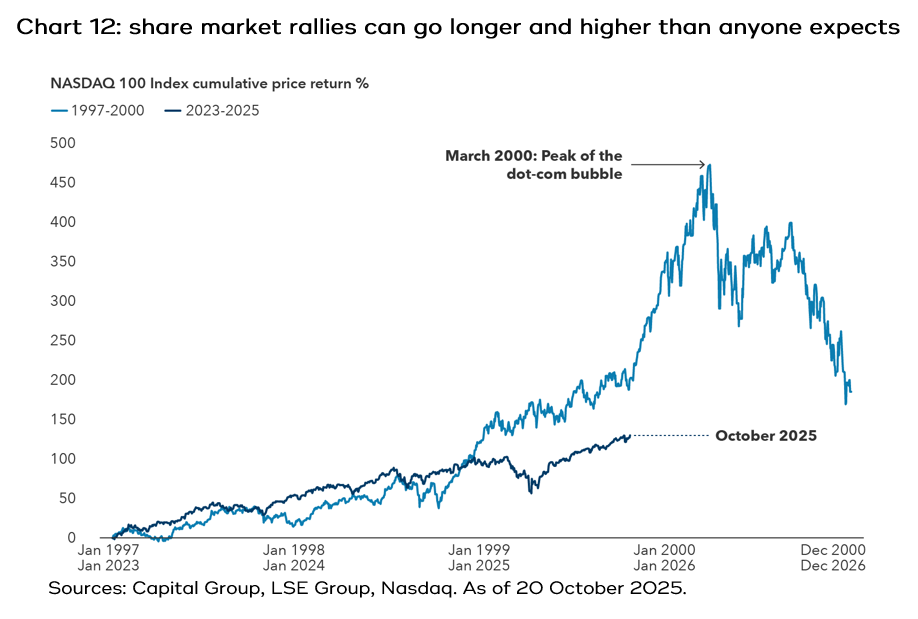

Secondly, even if you choose to be cautious and reduce your exposure to shares, timing markets is notoriously difficult. Chart 12 compares the NASDAQ, which is the index with the biggest weighting to technology, from the start of 2023, so just after the release of ChatGPT, to the dotcom rally. This isn’t to fall on the side of the argument that they should be seen as similar, more that share market rallies can go much longer and much higher than you might expect.

A telling story is that Alan Greenspan, then Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, gave investors a collective heart attack in December 1996 when he described US share markets as reflecting “irrational exuberance”. The NASDAQ didn’t peak until more than four years later, by which time it had risen almost four-fold.

CONCLUSION

Share markets climb a constant wall of worry, and there are times when the worries become more pronounced, which invariably coincides with the noise levels becoming increasingly shrill.

This is playing out right now, with the S&P 500 at the time of writing having fallen 3.5% from its recent high and the NASDAQ by 4.5% (the ASX200, which arguably has very little in the way of AI exposure, has fallen 7.1%). It should be kept in mind that over the past 30 years, the average intra-year decline for both the US and Australian share markets has been 14%, that is, on average, at some point during the year, the share market can be expected to fall by 14%.

There’s another old saying: bull markets don’t die of old age, and rarely do they die because of high valuations. There needs to be a catalyst to trip them up. In this instance, that catalyst might be an AI hyperscaler declaring write downs on capex, or announcing they’re stopping spending because they can’t see a way to profitability. Or it could be investors baulking at putting more money into an as yet unprofitable company like OpenAI, or an established company like Oracle defaulting on debt. Who knows?

Despite what you might hear or read from some commentators, unfortunately there is no way of knowing if a share market is in a bubble, or if it is, when it will pop. Clearly, you need to be able to sleep at night, so if markets are getting in the way of that, it’s prudent to reduce your risk by reducing your weighting to shares.

If, on the other hand, you are comfortable that volatility is part and parcel of investing in shares, and that it’s impossible to time markets, there are good arguments to remain invested in accordance with your risk profile, at least for now.