Ever since Donald Trump started campaigning to win the presidency of the United States, he made it clear that he thinks the US has been getting ripped off by its trading partners, and that tariffs offer the best solution to solve that problem.

However, most economists don’t agree with him, and as it turns out, neither do the US financial markets. When President Trump announced his planned tariff rates on Liberation Day in early April, the markets panicked, turning what had been a correction into a bear market.

A week later, he tried to placate the market’s concerns, announcing a 90 day pause on enacting the tariffs. From there, the US share market staged one of its fastest ever recoveries back to an all-time high.

But now we’re back to nervously waiting on a day-to-day basis to see what new tariff levels are going to be imposed on imports from the US’s trading partners.

It’s a roller coaster that has a lot of investors understandably nervous, yet the US share market has powered on, apparently unconcerned at the implications of a trade war that could well impact inflation, interest rates and economic growth.

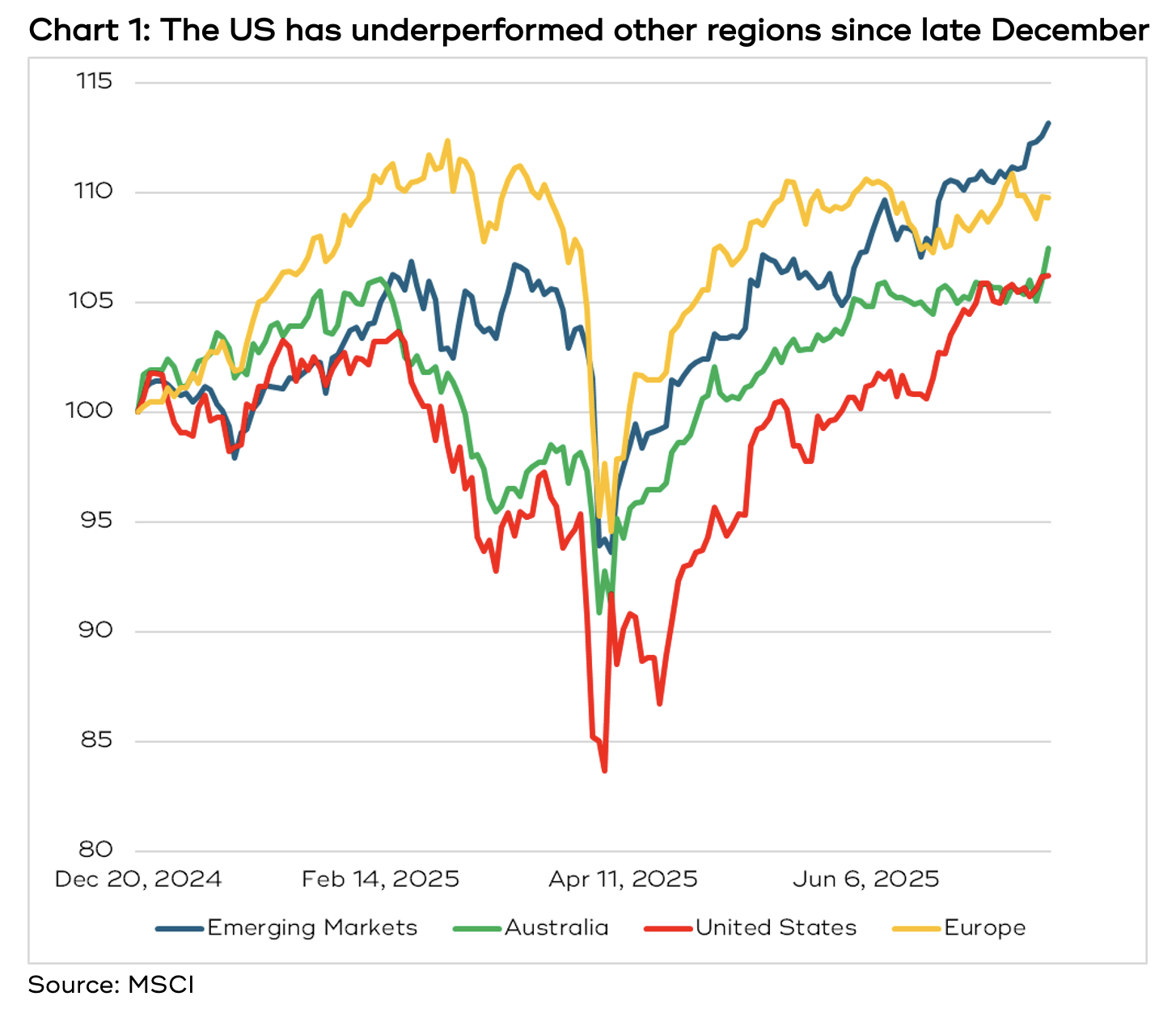

Meanwhile, even before Trump took office in January 2025, the European share market started to rally hard, with fund managers reallocating money away from the US and into Europe.

Then came Vice President J.D. Vance’s now infamous haranguing of European leaders in February, which spurred the market on even further as NATO members started talking about radical increases to government spending on defence and infrastructure.

While all this was going on, the US dollar suffered its worst start to a year in more than 50 years, which, for whatever reasons, tends to be a tailwind for the emerging markets.

Quite counterintuitively, given countries across South America and Asia would likely be heavily impacted by punishingly high US tariffs, it’s the emerging markets that have performed best since investors started hunting around for options outside the US.

Even the Australian market, which has endured two consecutive years of negative earnings growth, has slightly outperformed the US since late December – see chart 1.

Strategic vs Tactical Asset Allocation

Needless to say, any investor that had a well-functioning crystal ball could have come out well ahead by cutting US exposure and switching that to Europe and the emerging markets.

That process of overweighting one region compared to another is part of what’s called ‘asset allocation’.

A well-constructed, diversified portfolio will typically start with a Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA), which will be based on your risk appetite and reflect a long-term view of how much of a portfolio should be allocated to different asset classes (things like shares, property, bonds and cash) and geographies.

A portfolio’s SAA is unlikely to ever change (unless your risk appetite does) and will act as a kind of true north for the portfolio to return to, or be guided by, over the long-term.

But things crop up from time to time that might make one region more attractive than another, in which case, you can make a Tactical Asset Allocation (TAA) decision to shift some money toward that region.

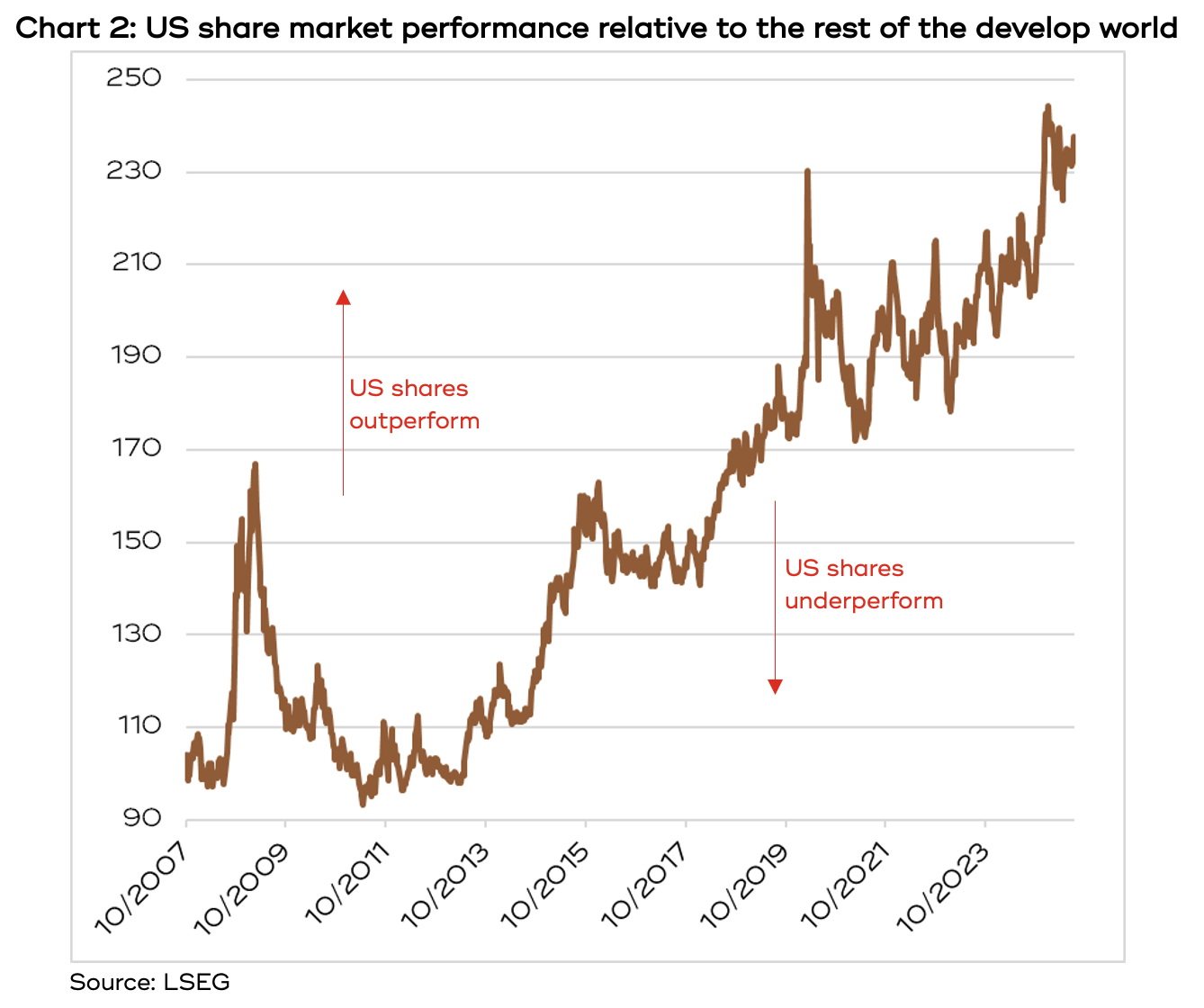

Since the European debt crisis of 2013, the US share market’s returns have trounced the rest of the developed world – see chart 2. In fact, Morgan Stanley calculates that since 2010, US equities have returned 13.5 per cent compound per year, more than double the 6.1 per cent of the rest of the world. That 7.4 per cent difference in returns compares to the median 4.9 per cent outperformance seen across four previous cycles: in other words, it’s an outlier.

That difference in returns has driven the US’s share of MSCI’s World Index to 64 per cent, a smidge below the peak it reached in the early 1970s. Meanwhile, Europe’s weighting has fallen to 15 per cent, way below its peak of 35 per cent reached in the late 1990s. As for Japan, its weighting has fallen to just 5 per cent, compared to a peak of more than 40 per cent in the late 1980s.

All that means any portfolio that is just reflecting the different country weightings will have two-thirds invested in US shares. Given the concerns circling around the US at the moment, it’s understandable some investors might see that as a lot.

So, what now?

One of the hot topics among market analysts this year has been whether the age of “US exceptionalism” has come to an end. Those arguing it has point to the slowing of US economic growth, the decline of the US dollar, and the trade war presenting the biggest potential own goal since Brexit.

There are, however, good arguments on the other side: it’s earnings growth that drives markets and the principal driver of US markets remains big tech, which continues to deliver. It’s entirely possible the AI investment cycle is still in its early days, and the US is very well placed to play a huge role.

Also, despite Europe talking about significant increases in defence and infrastructure spending, they continue to find it hard to break out of the austerity mindset that has hobbled economic growth for the past 15 years, so they’re looking to offset increased fiscal spending in one area with cuts in another.

Both Europe and the emerging markets are cheaper than the US, but they have been for years. Being cheap is one thing, but delivering earnings growth to drive share prices is another.

Australia, on the other hand, has struggled to post even positive earnings growth yet is still trading on a price to earnings ratio that’s 30 per cent above Europe’s and the emerging markets.

Having said that, Macquarie has just released analysis arguing Australian earnings growth is set to rise in 2026. Who knows, they may be right.

The bottom line

There’s lots of academic research showing that asset allocation can make a huge difference to a portfolio’s returns. But there’s also lots of empirical evidence that there’s yet to be a crystal ball that works.

If you feel strongly that one region is set to do significantly better than another, you don’t have to yank too hard on that lever. Find an ETF that invests in your preferred region and put a bit of money in it, but it doesn’t have to be a big bet. Remember, for professional investors, a shift in weighting of 3-4 per cent can be a big deal.