On the eve of the 2016 US election, Donald Trump was given next to no chance of winning the presidency, which was exactly how every financial markets commentator and prognosticator wanted it.

Markets thrive on predictability, but here was a candidate that shattered every preconception of what was “presidential” and was prone to what appeared to be unscripted thought bubbles. The randomness Trump was becoming known for might be fine for someone running their own real estate company but was potentially destabilising on a global scale for someone holding the most powerful position in the world.

Wall Street and the financial Twittersphere were forecasting a Trump presidency would be disastrous for the share market because of his threats of a trade war, his promises to make wholesale changes to regulations and his utter disregard for how politics had normally been done.

As it became clear on election night that Trump had indeed won, share market index futures plummeted around 5 per cent, triggering trading limits designed to arrest sharp declines. Then as the trading day progressed, the market surged upwards, with the S&P 500 finishing more than 1 per cent higher on the day, and it went on to deliver a total return of almost 22 per cent over the first year of Trump’s presidency and 79 per cent over his full four-year term.

The lesson is clear that any investor who tried to second guess the share market’s response to a Donald Trump presidency by reducing their investment left a lot of money on the table.

Once again, questions are being asked as to what the consequences will be for financial markets should Harris or Trump win the November election. The strong weight of evidence is that the best thing a smart investor can do is ponder the question as a matter of curiosity, and then move straight on to something else more productive, like play a round of golf or take the dog for a walk.

The Bespoke Investment Group analysed share market returns under all the different US presidents going back to the start of the twentieth century and found the median annualised return under both Democrats and Republicans was exactly the same at 6.6 per cent.

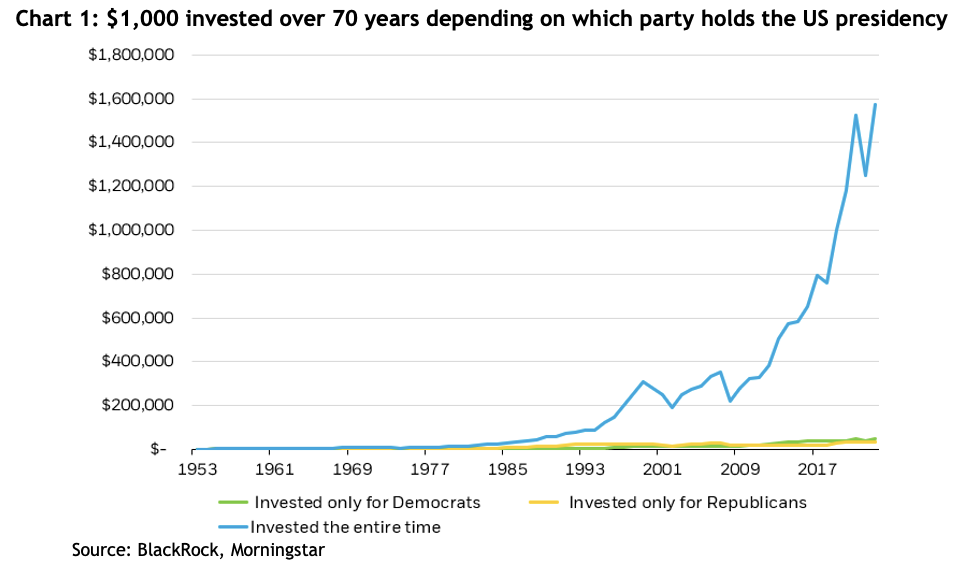

Letting your political beliefs get in the way of a long-term investment strategy can also be very costly. Going back 70 years, US$1,000 invested in the US share market only for the periods when a Republican was president would be worth US$27,400 today, and whilst the same amount invested under Democrat presidents would be worth US$61,800, just investing and leaving it alone over the full 70 years regardless of which party’s in charge would have seen it grow to US$1.69 million. – see chart 1.

As it happens, the average of the compounded annual returns across Australia’s different Liberal and Labor governments since 1983 has been 11.0 per cent for the three different Labor administrations and 11.3% for the two Liberal. So the same lesson applies to the Australian share market.

Geopolitical risk often seems like a dire threat to share market returns, but rarely turns out that way. The Ukraine and Gaza wars have been recent prime examples. Despite dark warnings for global trade when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the MSCI World index has risen more than 30 per cent since then, including navigating the headwinds of higher interest rates during 2022.

Likewise, in the 12 months since the Gaza war started, right on the doorstep of the region that accounts for the bulk of global oil production, the MSCI World index is up 27 per cent.

It pays to remember those analysts who specialise in geopolitical commentary, and who often find themselves in the limelight when major events crop up, might sound very well informed about political motives and consequences, but what share markets care about is the impact something’s going to have on company earnings. There may well be a dip while the market works it out, but as history shows, it generally pays to stick it out.

There’s a good chance share markets won’t make it easy to keep calm and carry on in the lead up to the election on 5 November. In the six US elections since 2000, the S&P 500 has averaged a decline of 3.7 per cent in the six weeks leading up to the election (though 2008 was an outlier). Share markets are doing well, so unless you’re sure you know something the market doesn’t, it’s a good time to enjoy the ride.