What you need to know about fixed income

This article appeared in the Australian Financial Review

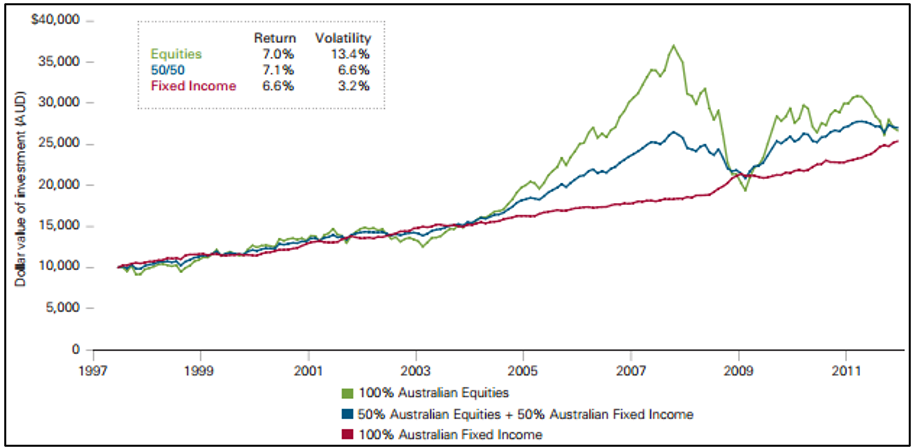

Every interest rate cut is another turn of the screw for investors looking for a decent, low risk return. Many a risk averse investor is finding they’re no longer able to rely on cash or term deposits to generate a reasonable return, and are instead considering other fixed income alternatives, of which there is an almost bewildering range. As usual, however, for every extra percent of return you try to get, you have to accept higher risks, so to avoid nasty surprises, you need to understand what those risks are.

The explosion in the number of fixed income managed funds, ETFs and LICs over the past couple of years has come as product providers sniffed an opportunity to meet the demand for income in a low interest rate environment. According to BetaShares, in F2019 more money went into fixed income ETFs than any other category, in fact, 60% more than Australian equities.

Investors need to be aware the name ‘fixed income’ covers an enormous range of products, and they come with an equally enormous range of risk. The last thing a risk-averse investor should be doing is dumping a bunch of money into the highest yielding fixed income product they can find, without knowing what they’re getting in to.

Here are some basics to help you understand what you’re buying:

- What is a bond?

A bond is a security that a government, or some other kind of entity like a company, issues that says ‘if you lend me $100 today, I’ll pay you an interest rate on that money (the yield), and every year I’ll pay you the coupon (the technical name for the amount of money paid, so if you have a $100 bond with a yield of 10%, the coupon will be $10) every year until the bond matures (it could be anything from 30 days to 100 years), and at the end of the bond’s life, I’ll give you your $100 back.’ It’s similar to a term deposit, except being a security, it can be bought and sold.

- A bond’s maturity is usually fixed

Most bonds, especially government bonds, will have a set maturity date. There are some perpetual securities but they’re few and far between.

- A bond’s yield will reflect the issuer’s credit worthiness

The less risk you’re taking to get your money back the less yield you’re going to receive. That can be reflected in an issuer’s credit rating from a company like Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s, but other factors also come into it. Interestingly, there are only 11 countries with a AAA credit rating from S&P, Australia being one of them, while the US’s rating is only AA+.

- Bond yields can be fixed or floating

A bond’s yield can either be ‘fixed’, meaning it will pay the same coupon until it matures, or ‘floating’, meaning the coupon will be above some kind of benchmark (like the Bank Bill Swap Rate or LIBOR) and will be reset to reflect that rate from time to time.

- Bond prices are not fixed

Bond prices can fluctuate, a lot. The average investor is almost certain not to buy an actual bond, but instead will invest in a fund or ETF, and it’s important to realise a fund’s unit price can jump around, depending on what kind of fixed income securities it invests in.

- What makes a bond’s price change?

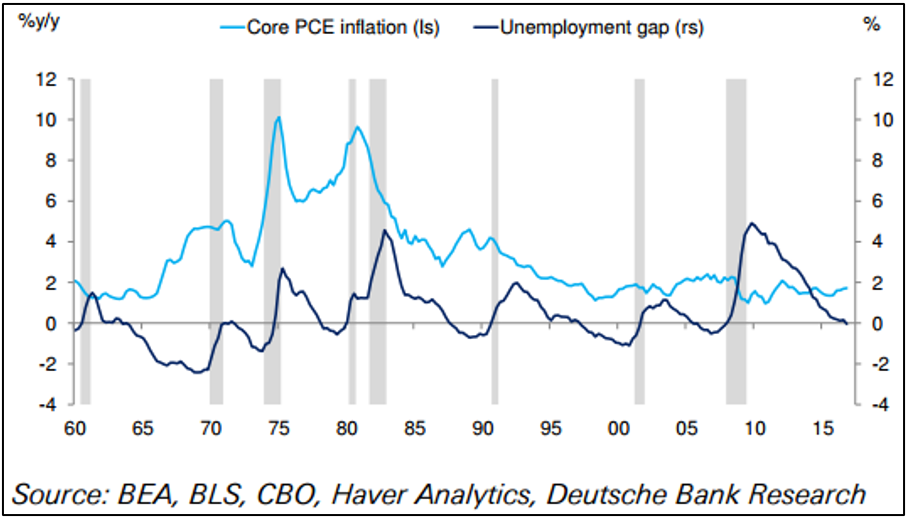

There can be a number of factors, but the main influence is expected inflation. If the market thinks inflation is falling, as it has recently, it will happily accept a lower yield to compensate for the reduced risk of the value of any future payments being eroded by inflation. If a bond’s coupon is fixed, meaning a 5% bond will pay no more or no less than $5 per year for every $100 bond, then it’s the price you pay for the bond that will increase instead. This is where you end up with the what seems weird at first: as a bond’s yield goes down, its price goes up, but in fact, it’s exactly the same as shares: if a share price goes up, its dividend yield goes down.

- Duration risk: the bond price’s sensitivity to changes in yield

A bond’s ‘duration’ tells you how much the price should change when the yield changes. For example, according to JP Morgan, the Australian bond index has a duration of 5.4 years, which means if interest rates go up by 1%, the price should fall by 5.4% (and vice versa if rates go down).

That’s really important because the longer a bond’s life, in normal times the higher should the yield be, which appeals to income-oriented investors, who are normally more conservative. However, while a bond’s maturity and duration are not the same thing, the longer a bond’s life the more duration risk it has, and with interest rates already so low, there is heightened risk they could go back up, and even if that’s only by a little bit, those longer bonds could lose a fair bit of their value.

- Credit duration: the bond price’s sensitivity to changes in ‘credit spreads’

Bonds issued by a company will typically pay a yield premium to reflect the increased risk that you might not get your money back. That premium is normally calculated as a certain percentage above some kind of benchmark, like the 90-day bank bill rate, and the gap between the two is called the credit spread.

‘Credit duration’ measures how much the price of the bond will change if the credit spread changes; a bond with credit duration of 3 years will fall 3% if the credit spread goes up (widens) by 1%, and vice versa.

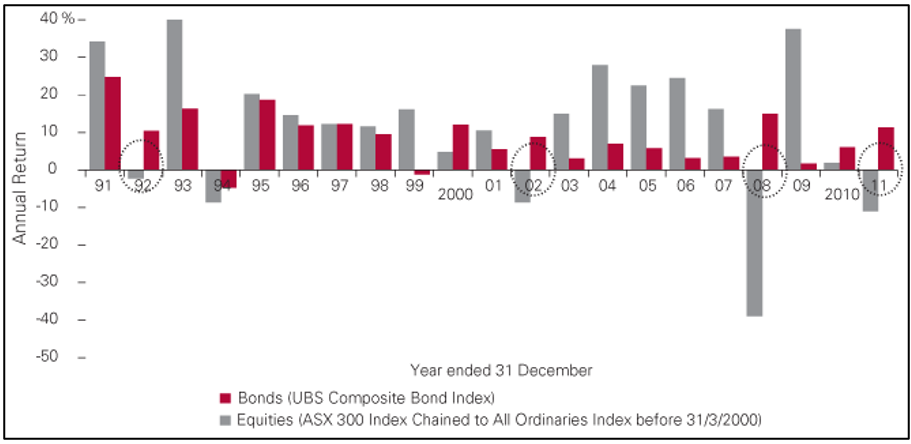

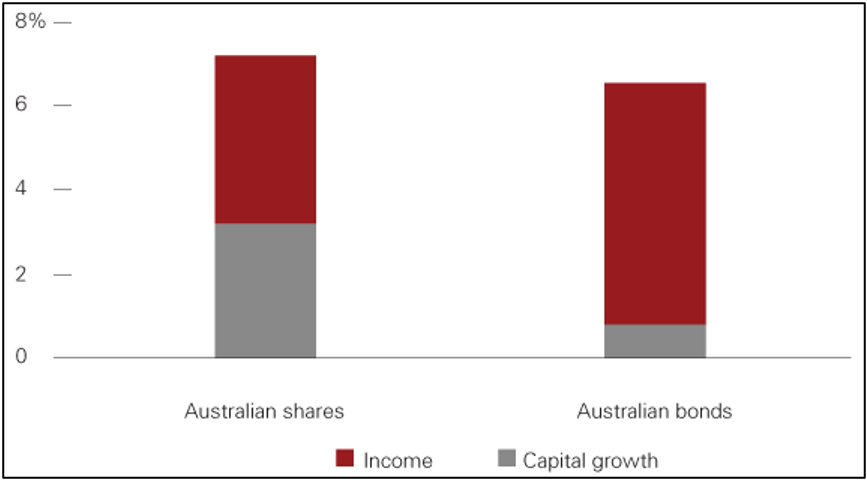

Bonds have had an extraordinary start to the year, with the benchmark Bloomberg Composite Index rising 6.5% to the end of June. But almost all that return is because bond yields have fallen, with the 10-year Australian government bond yield dropping a full percent to 1.32% to the end of June, and it’s now even lower at 1.09%.

In fact, bonds have been a great investment since the GFC as yields have plumbed record lows. If you’re going to invest in fixed income securities now, you are, in part, placing a bet that yields will continue to fall, which may or may not happen. For investors looking to replace term deposits, you just need to keep in mind that fixed income does not necessarily mean low-risk.