The outlook for residential property

Our asset allocation consultant, Tim Farrelly, has done a deep dive on what he sees as the drivers behind Australian residential property. Applying his usual analytical bent his conclusion is that falling interest rates over the past 30 years have been the primary driver of rising property values, but now those rates have probably bottomed. We think you’ll find it reasonably easy to follow and given how topical the subject is we thought it well worth publishing.

“If returns came out of history books, then librarians would be the richest folks around”

-Warren Buffett

Residential property has been a wonderful investment for millions of Australians over the past 30 years and longer.

So much so, that investors know that, despite minor short-term slow-downs, residential property will always show excellent capital gains in the long term. They know this because it always has been this way in the past. Their parents bought their first house for four thousand pounds and it’s now worth over a million dollars. Every house they have ever bought has made money. And, better still, everyone they know has made money on residential property. Not most people – everybody. Investing in residential property makes you rich. It’s an historical fact!

Well, almost. Unless they have been very unlucky, past investors in residential property have done well and that is an historical fact. As is shown in Figure 1, capital growth has been exceptional for a long period of time.

However, as Warren Buffett also noted, past returns and future returns are quite different things.

This Editorial looks to understand past returns from residential property and then to use that understanding as a basis for forecasting future returns. To understand where the price rises came from, it helps to be able to break apart the role of fundamental factors, such as growth in rents, from market factors, such as how much the market is prepared to pay for a dollar of rent.

In essence, this approach says that the price of a property is determined by net rents multiplied by the amount the market is prepared to pay for each dollar of rent. We call this the Rent Multiple. If we have a property that produces $10,000 per year in net rent and the market is prepared to pay $40 for each dollar of rent, that property is worth $400,000. For the property to increase in value, either net rents must increase or the Rent Multiple must increase – or some combination of the two.

Let’s look at an example using the property described above. If, over the course of a year, rents rose 3% and the Rent Multiple rose by 5%, the house price would rise by 8%. This is the increase in rents (3%) plus the increase in the Rent Multiple (5%) as shown in Figure 2.

Where this approach becomes very useful is in understanding the contribution of each factor to past growth in property prices. As can be seen in Figure 3, increases in rents have been very much the junior partner in this exercise. Prices have risen much, much faster than rents. That is to say that the increases in prices have not been backed up by increases in the fundamental earning power of property. What has driven the major part of the price increases is a huge increase in the Rent Multiple.

As outlined earlier, the Rent Multiple is the amount buyers are prepared to pay for each dollar of rent. The Rent Multiple is the inverse of the yield on a property. The yield is calculated by dividing net rents by the property value, whereas the Rent Multiple is the value divided by the net rent. As can be seen in Figure 4 (overpage), a soaring Rent Multiple means tumbling yields.

Clearly, the major driver of increasing housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne has been the huge expansion of the Rent Multiple. In the case of Sydney houses, the Rent Multiple has risen from around 15 times rents in the 1980s to a massive 65 times rents today – even after a period of softer prices. Other capitals have experienced similar increases.

From an institutional investor’s perspective, Sydney residential property is outrageously expensive. By way of comparison, commercial property trades at around 13 to 20 times rents and shares trade at about 16 times after-tax profits. As a result, institutional investors rarely invest in residential property.

Why is residential property so expensive?

farrelly’s believes it is because prices are set by those looking for somewhere to live rather than conventional investment metrics. Owners of residential property are, of course, largely owner occupiers, with a fair number of private investors. Both behave very differently to institutional investors who look at the earnings power of an investment and the potential for growth in earnings. In trying to make sense of residential property prices, it helps to think about how residential buyers and sellers go about deciding what to pay or accept for a property. From there, we will propose a theory of how prices might behave and then, finally, look at the data and see if our theory translates into the real world.

How home buyers decide what to pay for a property

How much do home buyers pay when looking for a house? The answer? Whatever they can afford.

Home buyers, after their first day of house hunting, invariably return deflated. “Is our dream home really that far out of our range? I can’t believe how little we get for our money.” After that first day, the buyers’ strategy becomes clear – work out the maximum they can possibly borrow and then go looking for the least worst place they can buy for that amount of money. Concepts like yields or the Rent Multiple just don’t come into it. They just want their own home to live in and in which to raise a family. So what do they spend? Whatever the bank will lend them.

The banks will assess a loan on the ability of the borrower to pay the interest. They compare the amount of the borrowers’ weekly income that can be spent on interest payments with the interest payments required on the amount borrowed. So, if the borrowers’ earnings rise, or if bank interest rates fall, the banks will lend more to a given borrower. Similarly, when interest rates rise, banks will lend less for each dollar of income. Borrowers want to maximize the amount they have to spend on their property and the banks are only too happy to lend it to them.

When interest rates fall substantially, buyers all over Australia simultaneously find they can borrow, say, 20% more to buy a fixed number of houses. You would expect that, in this environment, prices should rise by around 20%. And, more or less, this is what actually happens, if not immediately.

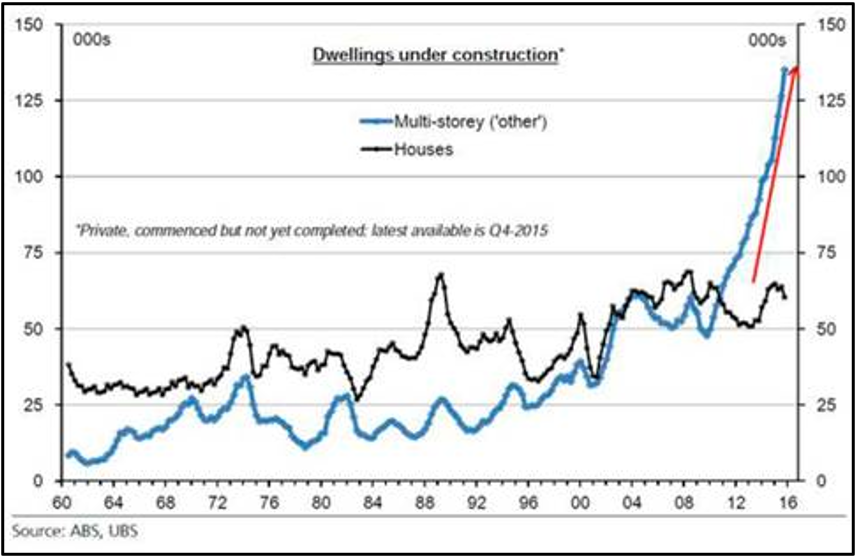

Note that this only works if the supply of houses is relatively stable. If the supply of houses responded rapidly to changing prices, bank lending would no longer drive prices to the extent suggested here. In Australia, we have some nine million dwellings growing at around a little over 1% per annum – and that is with a building boom underway.

Now, home buyers don’t automatically pay more for a given property just because they have had a pay rise and can borrow more. In practice, they study the market for a while, work out what is the going rate for houses in a particular area, and then go looking for a bargain, or at least something that seems reasonable. Sellers go through a similar exercise. They find out what other houses in the street have sold for and hope to get a price a little bit better than that.

The impact of thousands of such buyers, all making similar assessments, will gradually move prices up when average weekly earnings rise, or if interest rates fall. In the long term, prices should rise in line with the amount the banks are prepared to lend.

How investors decide what to pay

Because home owners aren’t the only buyers in the market we need to investigate the market impact of investors, who, as we have discussed, are rarely institutions who worry about income and how fast that income grows.

Private investors are more concerned with the amount of capital appreciation that may be achieved over a period of time, without being too concerned where that appreciation might come from. For a private investor, a bargain is a property that is cheaper than the house next door, even if both are ridiculously expensive from the viewpoint of an institutional investor.

Private investors believe that residential property will increase in value. Their experience, and the experience of just about everyone they know, is that property prices rise in the long term. So their process for investment turns out to be much the same as home owners. They work how much they can borrow and find a property at a half decent price compared to other properties in the area. And the banks’ attitude to them is much the same – how much interest can you pay and can they pay a deposit?

Affordability: theory and practice

Our proposal is that in the long-run, prices are set by home loan affordability which can be best thought of as how much the bank will lend to the average buyer. In effect, we do something close to the calculation a bank makes before deciding on a loan. The bank will start with the amount a borrower earns, work out what is left over after living expenses and therefore available to be used to pay interest, and then divide by the interest rate payable to arrive at an affordable value, or the amount the bank will lend.

If this works in practice, then we should see long-term prices following a path that is similar to that of the Affordable Value calculation. We should see prices rising as average earnings rise and as home loan interest rates fall. In the short-term, prices may move away from the theoretical Affordable Value – depending on the amount of buyers and sellers active in the market – but prices should come back over time.

Figure 5 compares actual median house prices around Australia with farrelly’s estimate of Affordable Value in different states. The results fit the theory well. As expected, in the short-term, prices seem to take a while to respond to changes in affordability and at times get driven beyond the levels one would expect if they were set by affordability alone. But in the long run, prices seem to follow the path set by changes in affordability.

Looking ahead

If affordability continues to be a key driver of residential property prices, then the major drivers of prices will be wage growth and interest rates, both of which depend to a large part on inflation.

Inflation

Forecasting inflation is a subject in itself. For the purpose of this report, we will assume that the RBA and RBNZ continue to have moderate inflation as one of their primary targets and continue to do an excellent job of keeping it there. Our estimate is for inflation to remain in the 2% to 3% per annum range, averaging 2.25% per annum, in Australia and 2.0% per annum in New Zealand. However, it is possible that inflation could be higher or lower than the targets and so we will also look at the impact of higher or lower inflation as well as our base forecast.

How fast can wages grow?

The data for average weekly earnings growth compared to inflation is shown below in Figure 6. What we see is that wages move broadly in line with inflation, generally with some scope for real growth, usually reflecting productivity increases.

Currently, real wages growth in Australia is very slow, reflecting the sluggish Australian economy. As the economy gradually improves, we see that picking up, but not too much. We expect average income growth at around inflation plus 0.75% per annum in the next decade in Australia.

Interest rates

In the long run, interest rates tend to be driven by many factors, but the key one is inflation, or expected inflation. It is our expectation that interest rates will increase modestly over the next decade to, say, 3.0% or 3.5%. Rates may even go higher. What they will not do is go much lower. Nonetheless, we can test the impact of a range of different interest rate environments on Affordable Values.

Affordability through to 2027 under different scenarios

We can test the impact on affordability of our base case and for a number of different scenarios. Nonetheless, given we need either high wages growth or falling interest rates to drive affordability, even without looking at the numbers, we can quickly see that growth in affordability is likely to be much slower than in the past. The various scenarios in Figure 7 make assumptions about what real wages growth and interest rates would be under different inflation scenarios. And, while the 1.5% to 4.5% range of inflation scenarios may seem narrow, moving outside those scenarios doesn’t change the remarkable conclusion from this review that almost regardless of what scenario we look at, the rate of growth of housing affordability is likely to be extremely low going forward.

This suggests that capital growth is likely to be around 2.5% per annum or less for the next decade, which, when added to the extremely modest rental yields on offer, suggests very modest pickings for residential property investors over the next decade, as is summarised in Figure 8.

While the analysis here is focused on the Australian market, anecdotally the same logic largely applies for the New Zealand market although farrelly’s lacks the data to back-test the affordability model in NZ. As can be seen here, the outlook for the Auckland residential property market looks much the same as that of Melbourne and Sydney, and for all the same reasons.

What could go wrong with this forecast?

Forecasts are based on assumptions, many of which could prove to be wide of the mark. In this case, there are many factors that could lower residential property returns below even these modest forecasts.

What could make returns even lower than forecast?

- Foreign investors become net sellers – this is possible, particularly if the markets show signs of weakness. In property markets like Hong Kong, investors are notoriously fickle. However, anecdotally, much of the foreign buying in Australia and New Zealand has been for lifestyle rather than investment purposes.

- Local investors become fearful, take flight and dump property – again, this is possible, but unlikely. There is a very strong underlying belief in property as a sound investment. It would take a long time to break that belief.

- Changes to the capital gains tax treatment or deductibility of interest expenses— again, this is possible, but unlikely to have too much impact. It may slow new investors entering the market but any changes would in all likelihood be grandfathered and so would not effect existing investors.

- Massive overbuilding – there have been signs of this in some suburbs of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane and, if building activity keeps going at current rates, that certainly would lower returns. However, building approvals are slowing and so the long-term impact should be modest.

- Even tighter regulatory controls on bank lending practices – this has already been happening to some extent and has been incorporated into this analysis. Further tightening of lending standards will further lower capital growth.

- Recession – this could hurt returns in the short term and medium term, as recessions tend to move the actual value below Affordable Value for a while. On the other hand, recessions tend not to impact affordability in the long term.

- Much higher interest rates – these would have little impact on nominal returns but could be devestating for highly geared investors. This is quite unlikely as central banks will be very cautious about lifting rates too far too fast.

- Legislation aimed at improving housing affordability by reducing housing prices – this is a real possibility but the impact will be targeted to slow capital growth rather than reduce prices substantially. This is a political tightrope – don’t expect too much from our politicians!

- Transaction costs – the cost of buying and selling a house normally comes close to 8% to 10%, enough to reduce returns by 1% per annum on a 10-year investment. This will apply to all new investors considering a residential property investment

What could go right?

Because these forecasts are somewhat pessimistic, instead of worrying about how the returns might be much lower than forecast, it is possibly more useful to worry about whether and how returns might be much more attractive than expected.

farrelly’s sees two main catalysts:

- The foreign investment floodgates open – this is possible, but unlikely. The New Zealand government has been on the housing affordability case for some time, with limited success it would seem. Now, even Australian politicians have woken up to the idea that this is a major issue for a large part of the population. Restricting the impact of foreign investors on affordability is too easy a win. If increased foreign capital flows was a factor that was really driving property prices, expect it to be shut down quickly.

- The politicians attack the affordability issue by making it easier to buy property – this is low hanging fruit. First time home buyer grants, allowing banks to ease lending criteria, allowing superannuation savings to be used to buy a first home – all just make the affordability issue worse. Again, this seems unlikely as most politicians seemed to have worked this out. But it is ripe for the populists.

Now is not a great time to be investing in residential property

Low returns, high transaction costs, and the threat of rising borrowing costs all make Residential Property a dubious proposition at this time, despite magnificent past performance.